What It's Like (And What It Takes) To Make a Textbook-Altering Discovery

What did you do at work today?

Neuroscientists have found a new bit of brain on the block, and Antoine Louveau, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Virginia was a key player in its discovery. When asked how he felt about contributing to something that's being hailed — by UVA press releases and an increasing number of his peers — as a textbook-altering piece of physiology, Louveau thought for a moment. "It's definitely a once-in-a-lifetime type of experience," he said.

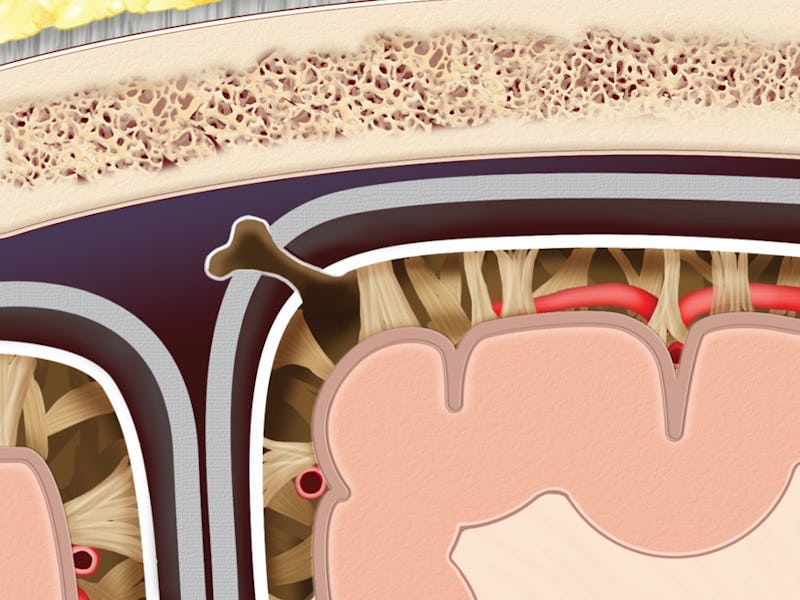

His discovery involves the interplay between the brain and the lymphatic system, a sort of bodily garbage-disposal route which transports lymphocytes (such as killer T-cells) and gobs of bacterial or protein trash. Since the 1950s, the dominant theory was that the brain, as an immune-privileged organ, had no direct lymphatic line. Any lymph cells in brain matter were thought to be signs off bad things afoot, neurologically speaking. But there are, in fact, vessels connecting the brain to the lymphatic system, Louveau and his colleagues published Monday in the journal Nature.

How did this series of tubes go unnoticed for so long? Louveau says that's because no one really looks at the meninges, a membrane that plays Saran wrap to the brain's sandwich. Many labs that examine rodent brains (Louveau made his discovery in mice) treat the meninges like so much plastic wrap, throwing it out before slicing the meaty brain into microscope-friendly sections.

"Meninges are full of immune cells," he told Inverse. "Their presence is important to maintain brain function. I became interested in that specific area: How did they enter and how did they leave?" He developed a new way to section mouse brains that carefully carves off the meninges crust, unlike the traditional method of slicing up a brain like bread loaf. A chemical stain on the mouse skull cap revealed vessels chock full of lymph cells — a shot in the dark that turned out to be an anatomical bull's eye.

"According to textbooks the vessels were not supposed to be here," Louveau said. "We were really excited." After a hunting through brain literature came up dry — the vessels are very easy to miss unless you know look for them — Louveau and his colleagues believe they have something revolutionary on their hands. They traced the vessels through the sinuses, and bingo: A functional part of the lymphatic system.

Louveau's next steps are to show that analogous structures exist in human brains. Because protein aggregation in the brain is associated with disease such as Alzheimer's or Parkinson's, it's possible — and this is all fairly conjectural, but now testable in a lab — that something is wrong with a brain's lymphatic system: clogged vessels, for instance, might allow proteins to pathologically clump. "If they exist in humans," Louveau said of the lymphatic vessels, "that makes all of our studies more relevant for human disease."