The Longest Autonomous Car-Ready Highway Nears Completion in Ohio

Fiber optic cable is being laid right now.

To put it bluntly, the westward drive on U.S. Route 33 from Columbus, Ohio can be a rather boring trip that winds through fields of corn. But if you glimpsed onto the shoulder of Route 33 this month, you might have seen construction workers digging trenches. In those trenches, they were laying thick orange fiber optic cables. It turns out that this unassuming state highway will soon become a testing ground for some of the world’s most advanced car technology.

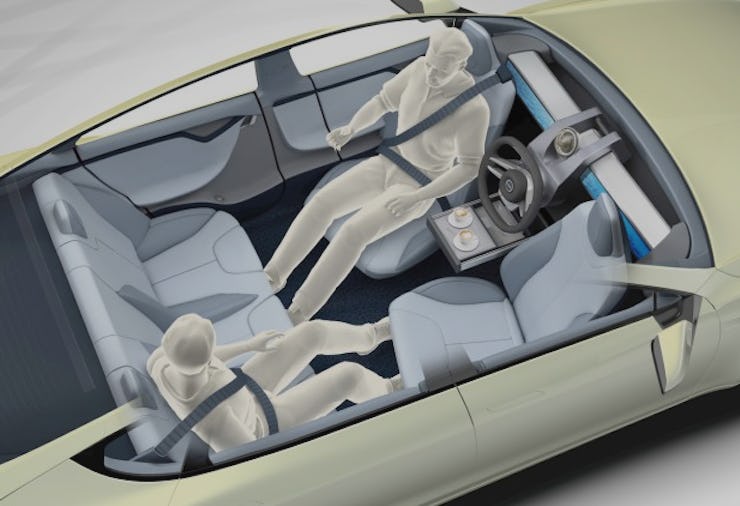

When finished, the 35-mile stretch from Columbus west to East Liberty, Ohio, should be longest “autonomous-ready” highway in the country. The road is being lined in fiber-optic cable to allow sensors along the highway to communicate with autonomous cars, using the wifi connection to inform the connected cars about upcoming traffic, weather changes, road conditions, and accidents. The sensors and fiber connection will be used for autonomous car testing along the route. They will also connect with government vehicles using short-range radio transmitters.

The $218 million project is intended to put central Ohio on the map for autonomous car testing and the future highway was born because a few towns along Route 33 had a very current-day problem: Their internet speeds were too slow.

The towns started to look into internet speed right as the Ohio government and the Transportation Research Center, the largest independent car testing facility in North America, started looking into expanding autonomous car testing. “It’s serendipity, I guess,” says Donna Goss, director of development in Dublin, Ohio to Inverse.

Suddenly, the sleepy towns of Marysville, Dublin, and Union County were able to apply for “smart mobility” grants in order to build modern internet infrastructure, as well as a smart highway. In practice, “smart mobility” is having cars that communicate with each other and things like traffic lights or turning lanes. The U.S. Department of Transportation, as well as the Ohio State Legislature, and Ohio State University award million dollar grants for projects to implement these technologies.

The miles of orange cable are six inches in diameter and can support seven different fiber cables, Eric Phillips, CEO of Union County Economic Development Partnership, tells Inverse. Only one fiber cable is being inserted now, and it will have 432 strands of fiber to support the internet needs of the local communities and the connected highway. The sensors along the highway will use the fiber internet to help run communication between cars fitted with receivers and sensors along the route.

The 35 miles of fiber-optic cables that connect Columbus and the Transportation Research Center in East Liberty, Ohio are currently being installed. The conduit and snaked fiber will be completed by the end of August. The internet will be up and running by the early September, and sensors will be installed along the highway next year to make it fully operational, says Goss.

Next year, communications towers using Dedicated Short Range Communication, short-range radio transmitters, will be installed along the route every 600 meters. One of the grants for the project pays to install wireless communication devices in 600 vehicles, which Phillips says will likely be Ohio government vehicles or school buses. The cars won’t be autonomous yet, but the communication between the cars and the connected infrastructure will start late summer 2018. Traffic patterns on the highway that sees 50,000 vehicles a day, and reports on how cars react to accidents and weather conditions will be recorded. This will give vital information for autonomous car development.

Although this is on its way to be one of the most high tech highways in the country, route 33 is not particularly futuristic looking.

Last year, Columbus won the $50 million Smart City Challenge to transform the city to have infrastructure that can communicate with buses and cars retrofitted or specifically designed to receive information from lights or construction zones. This allows for road testing of autonomous cars in Columbus, as well as paving the way for the use of fully autonomous buses along route in the city.

Between the Smart City Grant, and the autonomous higghway, Columbus natives hope that the projects will reverse the “brain drain” Ohio has suffered for decades, as the region’s brightest left for job opportunities on the coasts.

Reversing brain drain takes doing something that isn’t happening in the rest of the country, says Phillips. “We’ve got to innovate, we’ve got to look for different ways, and [smart mobility] is an opportunity that a lot of people haven’t taken advantage of,” Phillips tells me. In the last 14 months he says his town has gone from having slow internet to being the focus a major development that he hopes will make Columbus a little more like Silicon Valley.

Honda is taking advantage, and is installing autonomous communication devices in 200 of the cars that are used by plant employees as they drive to work along Route 33. People are hopeful it’s a sign companies will use the highway even before autonomous cars are on the streets. “Automakers, they’re not in the automotive business anymore, they’re in the technology business – they’re competing with Google,” Irene Alvarez, communications director for Columbus 2020, the economic development group for the region tells Inverse.

The Honda Plant in Ohio.

Supporters of the project hope that Ohio can develop it’s own “research triangle,” to draw engineers back to the state. The situation is similar to the start of the Research Triangle in North Carolina, when IBM moved its research labs in to the Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill area in the 1960’s. Today the Research Triangle area has 260 companies; most focused on engineering and tech. Phillips thinks that with the smart mobility highway, and connected infrastructure projects Columbus is posed to become a hub for transportation of the future.

“We won’t be exporting engineers anymore”

“I really want this area to be the new Research Triangle for autonomous and connected vehicles,” says Phillips. “If we become the Silicon Valley of smart mobility, or IoT, or smart tech, we won’t be exporting engineers anymore, they’ll want to come to Columbus.” And Columbus is doing its best to have everything ready for the first test drive of a fully autonomous car. If Columbus is lucky, the future of transportation might make its first voyage on a quiet highway that meanders through the cornfields.