Incredible Filter Can Clean Water in Fukushima-Like Disasters

A researcher and a high school student made a breakthrough.

Two researchers have created a filter that could greatly help with disaster cleanup Andrew Barron, from Rice University’s Department of Chemistry, worked with then-high school student Perry Alagappan to add carbon nanotubes to plain quartz fiber. One gram of the resultant fiber could get 83,000 liters of water to a standard acceptable by the World Health Organization for 11,000 people.

“The initial idea came from two different directions,” Barron told ResearchGate. “First, was the desire to be able to remove toxic metals from drinking water in remote locations that didn’t have power. The second was the Fukushima disaster, where there was a need to remove complex radioactive metal waste.”

The study, titled “Easily Regenerated Readily Deployable Absorbent for Heavy Metal Removal from Contaminated Water,” was published Thursday in the journal Nature. Beyond Barron and Alagappan, the paper lists Jessica Heimann, Lauren Morrow, Enrico Andreoli as authors. Heimann started the project but left to spend a year abroad. When Alagappan approached Barron to see if he could get some experience for applying to college, Heimann’s project seemed an ideal fit.

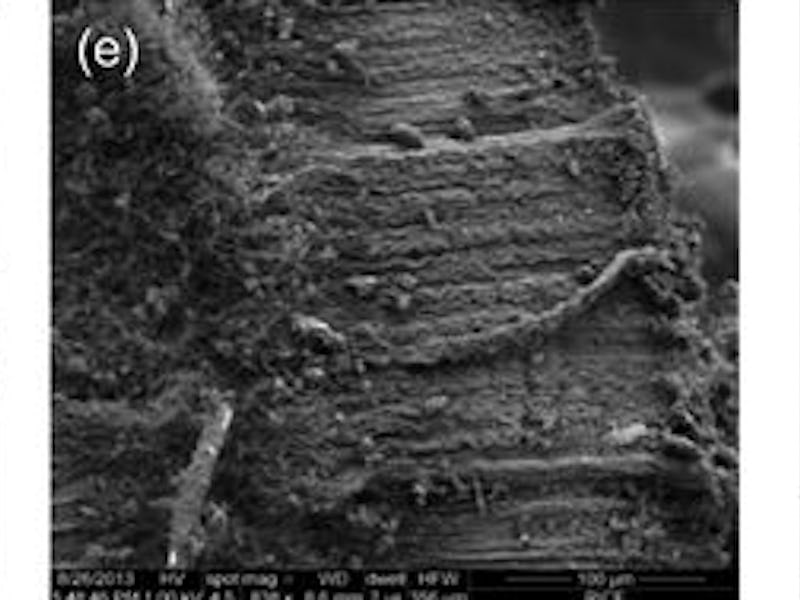

Figure a) shows the quartz wool prior to the carbon nanotubes.

Toxic metals contribute to pollution through five different sources: weathering, metal processing, metal usage, leaching of metals from waste, and metals found in excrement. The project was aimed at coming up with a simple, cheap solution that could be reused and deployed with ease.

The results were impressive. In tests, the filters absorbed over 99 percent of metals. Washing the material in vinegar allows the material to continue adsorbing the metals. The breakthrough has a wide number of practical applications, meaning the team can already start putting the filter to work to develop it further.

“The first is a test we have performed in Guatemala City demonstrated that highly polluted water could be pre-treated by a membrane and then flowed through the activated nanotubes to remove hazardous metals such as mercury and cadmium,” Barron told the publication. “We are also interested in developing the technology to remove metals from waste water from abandoned coal mines, which is part of an EU program called DE-MINE.”