How Salvador Dali's Mustache Stayed Twisted 27 Years After Death

‘It had nothing to do with embalming.’

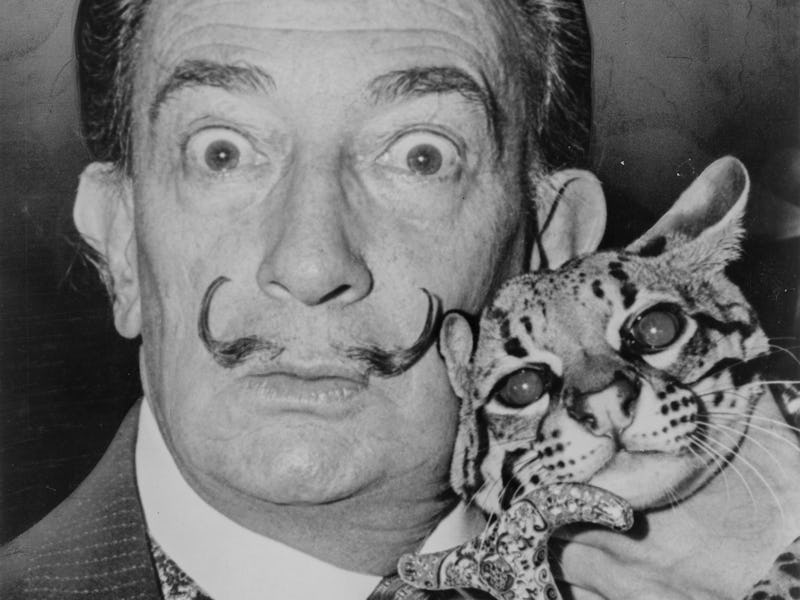

Nearly 30 years after his burial, Salvador Dali’s mustache has retained its exquisitely twisted appearance.

Forensic researchers exhumed the surrealist painter’s body this week to remove bones, nails, and hair for a court-ordered paternity test. Dali’s embalmer, Narcis Bardalet, witnessed the exhumation, and upon seeing the well-preserved mustache, told Catalan radio station RAC1, “It was like a miracle… his mustache appeared at 10 past 10 exactly and his hair was intact.” The “10 past 10” reference alludes to the way Dali bent and waxed his mustache to point as a clock does at 10:10.

The seemingly death-proof mustache, however, is no miracle, and it’s unlikely that embalming techniques had anything to do with its preserved state.

“The embalming has nothing to do with the survival of the hair,” Todd Howell, a licensed Tennessee embalmer, told Inverse.

Hair is already mostly dead, anyway. It contains no nerves, muscles, or blood vessels, which are required for infusing a body with embalming fluid. “There’s no way to distribute embalming fluid into the hair itself,” explains Howell.

Salvador Dali's "Oasis "(1946)

After 27 years, Dali’s hair should be expected to be in good shape, anyhow, says Howell. Hair simply decays at a much slower rate than organs and flesh. Locks of baby hair, for instance, retain their shape and color decades after being snipped off.

His distinctively bent mustache was likely molded in place by an oil-based product, or perhaps beeswax. “They probably put some product in it to give it its signature shape — which may have provided protection to the hair itself,” said Howell.

Dali’s exhumers reported that his body was in pretty good shape, too, suggesting that the embalming process was successful. It’s a tricky process: Before the formaldehyde-based embalming fluid is injected into the body — often through the carotenoid artery in the neck — all of the blood is first drained from the deceased’s body. The fluid, when injected, hardens the tissue and creates an environment that is inhospitable to most bacteria, delaying the decomposition process.

Dali's mustache has stayed at 10:10, even after 27 years in the grave.

But not all corpses are so lucky: The bodies of people who had poor eating habits, Howell says, often have compromised vascular systems. “If you eat a pound of bacon every day, the fats are going to clog your arteries — like crimping a water hose,” he says, explaining that this reduces the effectiveness of embalming.

“Embalming delays decomposition for an indefinite amount of time,” he continues. “Compromised vascular systems will have limited effects. The remains can last for two weeks, two years, or two days.”

Dali’s body is going on 27 years of preservation, so the embalming seems to be doing the trick. But even when his body finally does succumb to a hungry ecosystem of bacteria, his trademark mustache will likely remain bent upwards in its trademark twisted, surreal fashion.