Where the Next Climate Change Wars Could Erupt

Simmering political tensions plus weather shocks are a recipe for disaster.

The word “rival” comes from the Latin for sharing a river, and in a world of climate change, rivalries are bound to become more fraught. Changing weather patterns don’t cause war, but they can bring simmering tensions up to a boil. Syria’s protracted civil war, for example, was brought on by drought and crop failure, made worse by climate change, which heightened underlying political and social tensions until the country erupted under the pressure.

Hotter temperatures alone push people quicker to anger and violence. But the real problems come when the climate shifts affect resources — food, water, land. In a world of climate change, finite natural resources are both diminishing and shifting, and they do not respect property or political boundaries in their migrations.

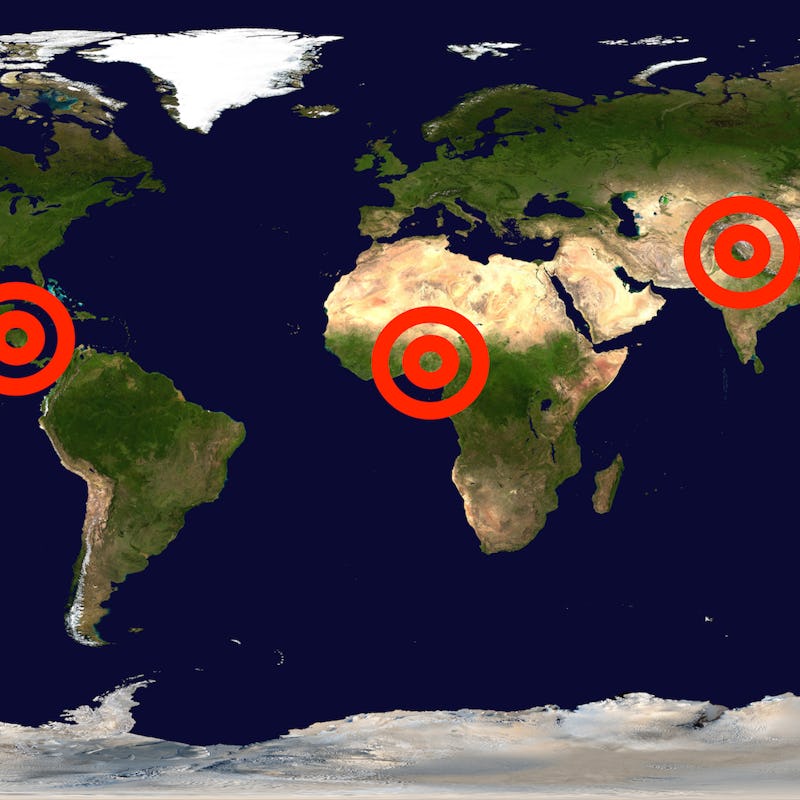

This month, the Center for Climate and Security published Epicenters of Climate and Security: The New Geostrategic Landscape of the Anthropocene, which documents the intersection between climate risk and conflict risk. Based on the report, we’ve highlighted five regions to watch.

The places in the world that rely on fish the most are also the places where catches are expected to decline.

Fish Wars in the South China Sea

The South China Sea is a hot potato of international diplomacy for a slew of reasons, but fishing is among the biggest. “Vietnam and China have repeatedly clashed over fishing rights in the South China Sea, including a 2005 incident where Chinese patrol boats opened fire on Vietnamese fishing trawlers, killing nine crewmen,” writes Michael Thomas of the Center for Climate and Security.

Climate change heightens the risk of wars over fish in at least two ways. For one, it moves the resource around, pushing fish out of their normal ranges as environmental conditions change. If fleets follow the fish, they are more likely to sail into dicey political waters and incur the wrath of foreign vessels. Secondly, climate change can cause declines in fishing stocks by killing off crucial coral reef habitat and destabilizing the food webs that the fish depend on.

The region hosts more than half of the world’s fishing fleet, and the fisheries’ resource has declined an estimated 70-95 percent since the 1950s. The potential for conflict is huge, and the stakes are unimaginably high. “China is the most advanced and uses its 200,000-strong fishing fleet as a ‘maritime militia,’ operating with impunity as an irregular naval force, claiming islands, ferrying goods and materials to assist the [People’s Liberation Army] in port and military base construction, and collecting maritime intelligence inside the so-called nine-dashed line,” Thomas writes. “Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia and the Philippines have all blown up or threatened to blow up vessels that enter ‘their’ waters and regularly use their navies to intercept and destroy foreign fishing vessels.”

What happens in China does not stay in China.

River Wars at the China-India Border

China controls the Tibetan plateau, which provides water to two billion people. But the country has water issues, with more than a fifth of the world’s population and just seven percent of the freshwater. Imagine how India felt when, in 2013, China suggesting diverting water headed south so that it might refill the dwindling reserves of the Yangtze River.

“The statement that nuclear explosions could be used to blast a passageway through the Himalayas conveys a threatening security message to the sub-continent downstream,” writes Troy Sternberg of the University of Oxford. And it’s conceivable that glaciers melted from global warming will stress the region enough to spark a real water war. “The potential for the two most populous and nuclear-equipped nations going to war dwarfs anything the Middle East can present.”

Sub-Saharan Africa is very vulnerable to climate-driven conflict.

Cattle Wars in Nigeria

Nigeria is vulnerable to climate conflicts on a number of fronts. Cities along the coast are vulnerable to joint pressures of urbanization, political instability, social unrest, and climate change effects. But further inland, in the country’s Middle Belt, a conflict is already brewing that has killed thousands of people in a resource war that will only intensify as the region heats up.

The conflict, in simplified terms, is playing out between farmers and migratory cattle herders who are fighting over access to grazing lands that are increasingly drought-stricken and degraded. The 2015 Global Terrorism Index noted that militants among the Fulani herders were the fourth most deadly terrorist group in the world. They killed more people in 2016 than the more infamous Boko Haram.

Central America is very vulnerable to shocks that affect coffee production.

Coffee Wars in Honduras

Honduras relies on coffee exports for an astonishing five percent of its GDP. And coffee is a particular crop, more sensitive than most to climate shifts and the things that come with it, including pests and disease. “The coffee plant is highly sensitive to temperature and rainfall variations and has a narrow range of optimal conditions, outside of which bean quality and yield decline,” writes Shiloh Fetzek from the Center for Climate and Security.

By 2050, the optimal altitude for coffee production could climb up the mountainsides by more than 600 feet. It’s easier to move a plant than land title boundaries, and for smallholder farmers following the plants to their preferred environment just won’t be possible.

The country got a taste of the hardships to come in 2013, when a severe outbreak of the fungal disease called coffee leaf rust cut the region’s crop in half. Coffee leaf rust can’t survive at temperatures below 50 degrees, which normally limits its spread. But in a hotter future, more and more precious coffee will fall victim to this blight, stressing social and political relationships.

Ice-free Arctic summers will be the norm by the middle of this century.

Oil Wars in the Arctic

Nowhere on the planet is changing in the face of global warming as dramatically as the High Arctic. The region was very recently an impenetrable fortress of snow and ice, but today oil rigs are making forays, and bigger and bigger cruise ships are boldly making the passage. The entire Arctic Ocean could be seasonally ice-free by the middle of this century.

While the Arctic is notably governed through peace and cooperation between neighbor states, that doesn’t mean everyone always agrees. A border dispute still looms on the continental shelf, north of where Alaska meets Canada, which could become significant if fishing and oil extraction become profitable in the region. There’s a further dispute over whether the Northwest Passage is internal water to Canada or as international strait of passage. So far, shows of military presence by the United States have not produced a major diplomatic crisis, but stakes will go up as the region becomes more accessible and valuable.

The claims of Russia to the Arctic complicates matters. “Since Russia’s incursion into Crimea and eastern Ukraine, each member state of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) has suspended all forms of military cooperation with Russia, including in the previously apolitical zone of ‘military cooperation’ in the Arctic,” write Francesco Femia and Caitlin Werrell of the Center for Climate and Security. “In a context of possibly greater interaction between Arctic nations (due to melting ice), but less cooperation due to diplomatic conflicts elsewhere in the world, the probability of heightened tensions between major powers increases. While the current probability of conflict in the Arctic is low, the future is uncertain due to a rapidly changing physical and geopolitical landscape.”