Tanning Is Actually the Sun Slaughtering Your DNA

Getting that sexy summer glow isn't so sexy from the perspective of DNA.

The sun is a mighty thing. It pumps out 389 million billion billion — not a typo — watts of stellar radiation every second, 174 quadrillion of which strike planet Earth. To step outside in the daytime is to wander into the firing line of the most powerful energy blaster for more than a parsec.

Mostly, that’s actually pretty good news. All that energy turns the sky blue, powers solar arrays, and supports all life on the planet.

Oh yeah, it’s also the basis of that summer glow — the tan — that so many pale humans are in pursuit of. We’re in the firing line of a wavelength of just over 300 nanometers on the low end to about 400 nanometers on the high end, which is part of the ultraviolet, or UV light range.

And not all of it is good.

It’s “sort of basic organic chemistry,” according to Sherrif Ibrahim, a dermatologist and skin cancer expert at the University of Rochester Medical Center.

A little primer back to high school: DNA is a long molecular structure, replicated over and over in the nuclei of each of your cells. It contains the instructions your cells use to survive, go about their business, and reproduce into new cells, written in a chemical code of cytosine (C), guanine (G), adenine (A), and thymine (T).

When sunshine lands on your skin, the UV light enters your cells. Photons slip between the walls of the nucleus, landing on individual, chemical letters of your DNA strands. Most of those photons dissipate harmlessly, reflected or transformed into heat.

But some don’t. Those photons strike the thymine in your DNA with just the right activation energy to mess with the covalent bonds — links of chemical energy — that hold them together. And when that happens, they transform.

Moments after the UV strikes your skin cell it leaves behind DNA rewritten. A “T” is scratched out, replaced with an “A.”

The good news is your body is pretty skilled at responding to and repairing DNA damage: Your cells have little copy editors wandering around their nuclei, enzymes that spot errors in strings of DNA. Those enzymes notice most of the irregular “A”s, and tear them out, replacing them with “T”s.

That’s also when tanning begins. UV light blasts your skin, leaving by invisible legions of mutations. And the cells that make up most of your skin — keratinocytes— send out emergency signals to specialist cells, known as melanocytes.

A diagram represents melanocytes in the skin

Melanocytes are less common in your skin. There’s just one of them for about every 36 keratinocytes. But they’re powerful.

“If you look under, say, an electron microscope, it’s absolutely fascinating,” Ibrahim said. “You’ll see the melanocytes are like little spiders that extend out their arms. They make the melanin, which is [a dark, sun-resistant] pigment, and they package them into these little balls, called melanosomes, and they distribute these melanosomes to these 36 keratinocytes.”

When the keratinocytes send out their distress signals — MUTATION! MUTATION! — the melanocytes dump extra melanin into their neighboring cells. That melanin forms a protective shield over those cells’ nuclei, protecting the vulnerable DNA hidden inside. And your skin darkens, and you get a tan.

But that process doesn’t begin until after the damage has been done, Ibrahim said. “Tanning is the body’s physiological response to DNA mutation. So nobody tans unless their skin cells are detecting mutations to DNA,” Ibrahim said.

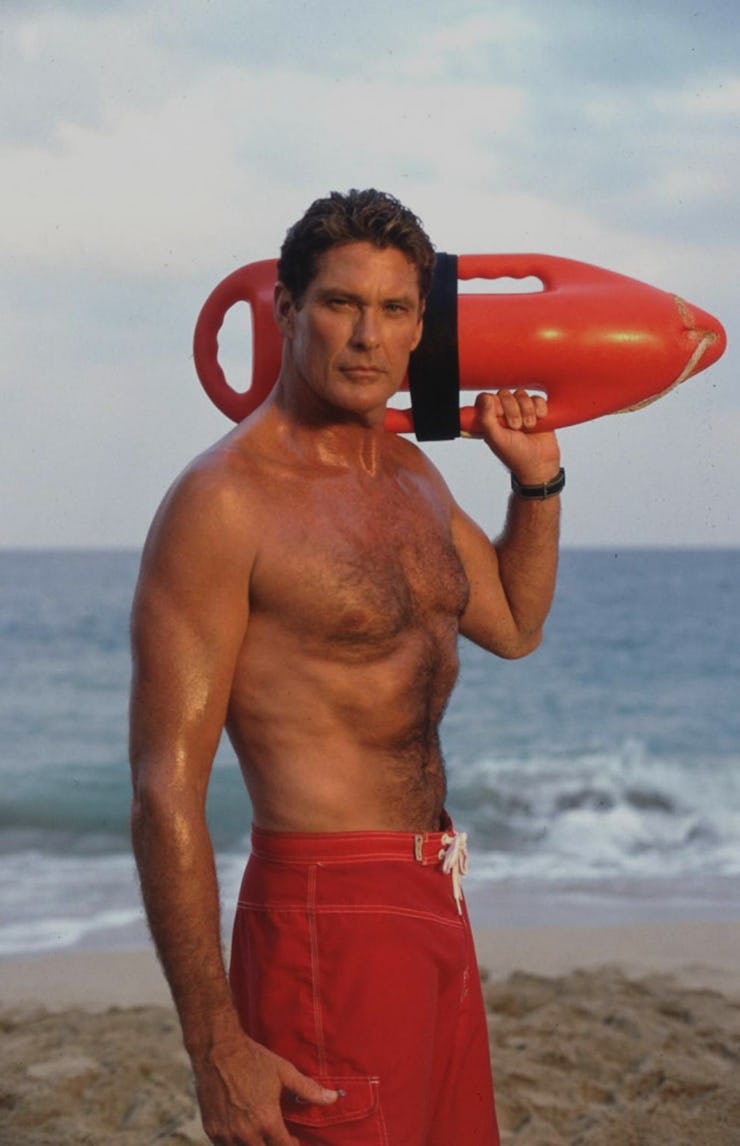

People sit under umbrellas on the beach in England.

Those mutations are bad news for people who like to tan, because they can get out of control. Enzymes within the body will handle the bulk of the mutation damage. And if things get really bad, your cells commit mass suicide to protect you. That’s a sunburn.

“But if you’re acquiring a lot of these mutations, then obviously some will slip by the body’s defenses,” Ibrahim said. “And as you get older you’re going to eventually get more of these mutations that slip by the body’s defenses.”

He said many of his patients seem to think that they should get and maintain tans throughout the summer to protect themselves from burns. But every bit of skin-darkening DNA-mutating sun exposure adds up over a lifetime. And some of those mutations will strike genes that limit growth and prevent tumors. Once that happens, cancer can strike.

How do you protect yourself? The only good answer is sunscreen, Ibrahim says — and lots of it.

Ultimately, the best skin is when you don’t tan at all, even under a full sun. “You want to be outside and not have your skin change color at all,” he said. “No redness, no brownness. That’s when you’re adequately protected.”