How Silicon Valley Turns Evil in 'The Circle'

Director James Ponsoldt says data can go too far.

The Circle, the titular tech company in Dave Eggers’s 2013 novel and the new movie adaptation starring Emma Watson, is a near-future behemoth, the most powerful and pervasive corporation in the world. It has the strength to bend governments and citizens to its will but prefers to coax them into surrendering their privacy in exchange for consumer comforts. It is an amalgamation of Facebook, Google, Apple, and Amazon, among others, and just like its real-world counterparts, offers its services with a smile and strategically altruistic mission statement. And just as in the real world, it’s a bit unclear just how much we should trust it.

“It was interesting trying to figure out what does this place have to do with the way that my cousins get their news?” he told Inverse last week. “Is the way that these people are living, and the ethical and moral questions that they are begging as far as their responsibility, is there a connect or a total disconnect?”

The company begins its rapid ascent with the advent of TruYou, which allows a user to log into every site and app using their real name, making usernames a thing of the past. CircleSurveys collect volumes of information from people about their habits as consumers, while Retail Raw calculates how much money influencers inspire followers to spend. Homie is a piece of hardware that scans a customer’s home and reorders products for them when they’re running low (think of an automated Amazon dash button). CircleSearch tracks people’s physical movements, while SeeChange, powered by tiny HD cameras the size of a marble, puts the entire world on film.

Ponsoldt spoke with Inverse about The Circle, its real-world predecessors, and how spending years working on his film helped shape his perception of Silicon Valley and its insatiable leaders.

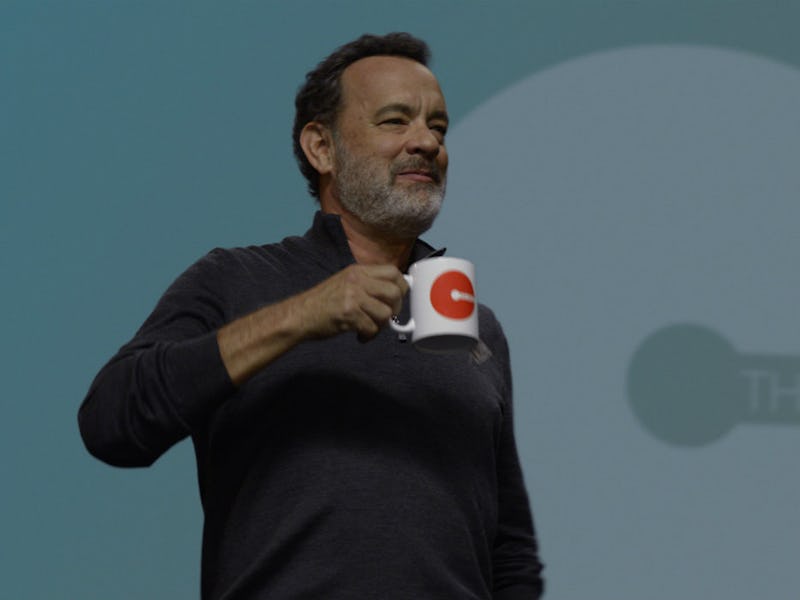

Casting Tom Hanks as The Circle’s leader, Eamon Bailey was counter-intuitive but clever, because who doesn’t want to believe in Tom Hanks?

Ponsoldt spoke with Inverse about both The Circle and its real-world predecessors, and how spending years working on his film helped shape his perception of Silicon Valley and its insatiable leaders.

Everybody does. He’s America’s most-trusted man.

Do you think that the people who run these companies are as altruistic as they say? That The Circle’s Eamon Bailey — and Mark Zuckerberg — really want to connect people, [I think] and Elon Musk wants to save the world? Or is it a scam?

If someone’s saying, “We want to empower people to have all information available to them,” or, “We want to allow you to stay in touch with your friends and family even though you can’t buy a plane ticket,” or, “We want to give you a platform to start a revolution,” — I think there is something idealistic, probably, behind most of those ideas. Then it’s put into practice and becomes a huge business with basically no government oversight. And it is in a company’s best interest to have as much information on its users as possible to predict, what? How to serve them better and make them better consumers. I think it’s not in the nature of companies to self-regulate, or get small or downsize voluntarily because it’s the more ethical thing to do.

It’s in their nature to grow and grow and grow. If you look at the history of monopolies in America, they grow until the government steps in and breaks them up and stops them. Not knowing these people, [I think] it is probably fairly ethical if the initial impulse is the desire to give something away for free. But I don’t know that anyone should possess that much power and information.

No one had to steal all of our information from us. I don’t think I’ve been monitored by the CIA or the NSA. I don’t know, maybe you have. We know that they could. We certainly know very public instances of what their abilities are, but there’s probably just as much information that I gave away without even thinking about the ability to opt out or reading the fine print on the apps on my phone. But they make it seem so bubbly and fun. I’m like, “I was distracted by this shiny object.” We all are. I don’t think it gets as binary as like, “I like technology” or “I’m technophobic.” It’s actually, one can love technology but just have a deep problem with all of your data being taken.

What makes the story here so alarming, versus something like The Hunger Games, is that we are slowly creeping toward it, and there’s no one big enemy to stop or an obvious evil. It’s all inevitable.

You hear about during the height of the Cold War in East Germany, where the Stasi had more data collection on its citizens than ever before in history. Around a third of the country were just informing on each other. So in any situation, if there are three people in a room, we know one of us is a collaborator with the government and has to inform, so are you going to say something bad? Why would you do that? You would just say, “Man, it’s a really beautiful day. That was a wonderful drink.” “How are you feeling?” “I’m feeling great.” We’re all on best behavior.

So as an artist or an individual, I think maybe it does in certain situations make you a better, less negative person — obviously with a big asterisk. But I feel like crap in the mornings where I’ve had coffee, and I want to speak my mind, and just be a genuine, honest person. I think what it curbs is our central humanity, and our ability to be honest.