When Billy Joel plays Madison Square Garden in New York City, he doesn’t drive. Instead, from his house on Long Island to Manhattan, he commutes by helicopter. The Piano Man breezes over the city that never sleeps, skipping rush-hour traffic along the way. In the future, Uber imagines a world where everybody gets to be Billy Joel.

Uber’s held a two-day Uber Elevate Summit in Dallas this week and after Day 1’s splashy announcements and fantastical predictions, the schedule got a little more down to Earth on Day 2. There were two panels about the expected noise they’ll make. Yes, the nitty-gritty of urban air travel isn’t as exciting as a rockin’ Joel gig.

Uber first introduced the world to its grand plan for urban air travel in October. After the initial enthusiasm subsided, the company’s flying-car ambitions mostly stayed out of the headlines as various unrelated scandals, transgressions, and lawsuits took their place. In the five months since the ride-sharing company announced UberAir, the company has clearly done a ton of work, particularly on thinking through the difficult challenges of adapting air travel to dense urban environments.

There are four challenges facing our flying car future, as laid out on Wednesday.

One air taxi, please.

Who’s Going to Build the Vertiports?

At the core of UberAir is the vertiport, which seems like a combination between a heliport, taxi stand, and small airport. The company is working closely with HeliExperts, a consulting firm run by Ray Syms and Rex Alexander that specializes in designing and testing the ground infrastructure required for helicopter flights. While Uber has dabbled in the helicopter charters business before, Syms immediately made it clear that vertiports are being specifically designed for a small, all-electric, VTOL craft. The finished product might not even accommodate traditional single-rotor helicopters. Syms and Alexander displayed elaborate concept designs on Wednesday, working through the complicated equations behind flying and landing hundreds of aircraft in the same place over time, including the design of the landing pads and the airspace requirements for takeoff and landing patterns. They settled on a hexagonal design, with five parking spaces for charging or waiting aircraft arranged around a single flight pad.

Here's what the vertiport in Dallas would probably look like.

That design could be modified to fit different situations too. In Dallas, a central terminal (the two gray hexes in the middle) would be surrounded by parking/loading spots, mostly so that people wouldn’t have to walk across a platform filled with aircraft and spinning rotors and wind.

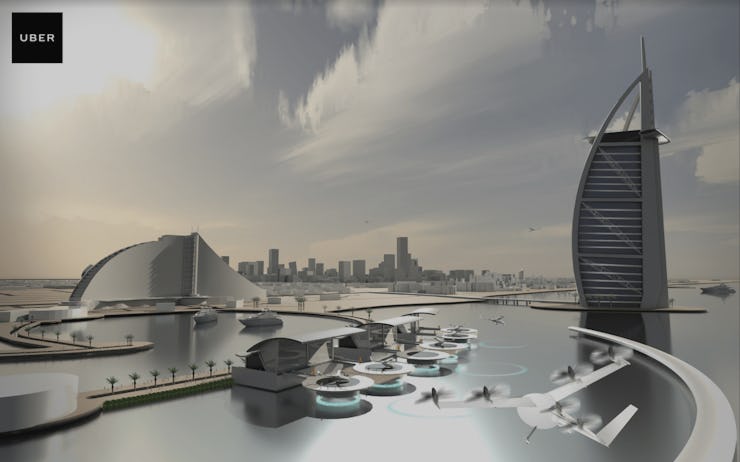

Here's closer to what it would look like in Dubai.

In Dubai, however, Uber was experimenting with the idea of a pier or barge-based system, with two floating landing pads parallel to a line of loading/ charging stations. Airports are often built near water, because the lack of buildings at sea usually ensures that approaching craft won’t run into stuff.

Let’s Talk About Batteries

While the exact specifications of Uber’s VTOL aircraft are still unclear, vertiport development seems like it’s pretty far along. On Wednesday, the company formally announced its partnership with ChargePoint, a green-energy EV charging startup that has already constructed an extensive network of charging stations tied together by an online app and network. ChargePoint will build a new charging system for Uber’s vertiports specifically designed to power VTOL craft, which will have higher energy demands than ground-based EVs. The system will be built on ChargePoint’s Express Plus charging platform, which pumps out 400 kW of power to a single vehicle.

“Uber is looking to the air as the next logical place to deliver on-demand transportation,” Nikhil Goel, Head of Product for Advanced Programs at Uber, said in a statement. “We knew the eVTOL vehicles we bring to drivers would need to stay charged in order to serve as many drivers as possible, so we went directly to the leading EV charging provider to find the solution.”

Uber’s internal data projections show that the company is hoping to have a battery and charging system that can bring vehicles from 20 to 90 percent charged in 15 minutes. It’s also hoping that the system will be modular, so batteries can be swapped out during peak times to take charge time off the board entirely.

Eventually, all of these trips will be autonomous.

The Noise is Getting Out of Control

One of the biggest problems in urban aviation is noise. Planes and helicopters are noisy to a fault, and property values underneath the flight paths of airports are much lower because no one wants to live under the constant noise. This is part of why Uber sees electric VTOL planes as essential to urban mobility. It’s not so much about saving the environment as it is controlling noise so vertiports can get through local legislation and zoning without a ton of public disapproval. To start gauging this, Uber is working with Siemens to do comparison tests on electric engines and combustion engines. Siemens has a new electric engine plane that’s much, much quieter than the same vehicle with a gas engine (14.5 decibels quieter, to be exact). Check out footage of it here (some of which was used in Siemens’s presentation):

Autonomy and Jobs and Pilots

The final part of Uber’s plan, of course, is autonomy. Despite the fact that Uber currently operates as a ride-sharing service built on the labor of a massive workforce of freelance contractor drivers, pilots and humans were rarely discussed Wednesday. Uber is clearly building its next-generation transit empire without a human element in mind, although it also recognizes that functional autonomy will take much longer to implement in the air than it will on the ground. Syms, the helicopter expert, estimated that UberAir will begin with human pilots, and then eventually proceed toward autonomy, a viewpoint that seemed in line with the rest of the presentations. The FAA’s guidelines for fully-autonomous flight are even more un-formed than the Department of Transportation’s judgment on autonomous cars, so the question of autonomy still seems pretty far out for the company. Eventually, however, the only chauffeur the company’s customers will need is a driving, flying, Ubermobile.