3 Questions About the New Copy of the Declaration of Independence

The new copy highlights the debate between states and a national identity.

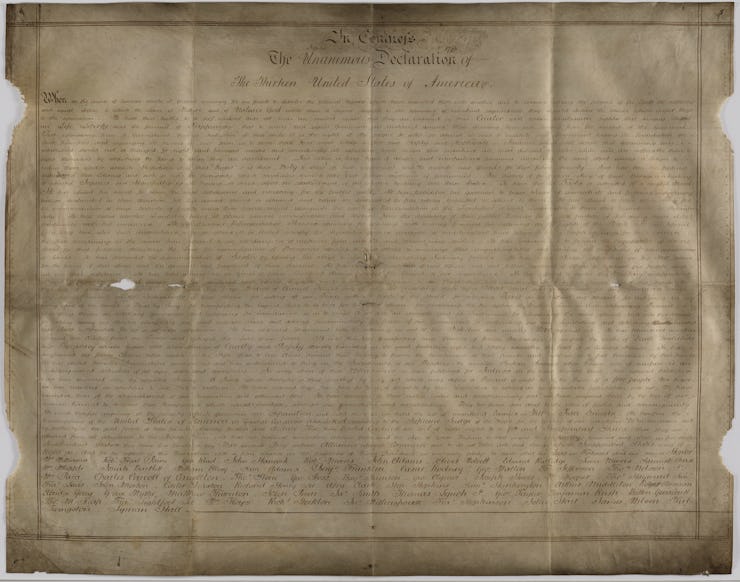

Before researchers announced last week their discovery of a new parchment manuscript of the Declaration of Independence, the only ceremonial parchment version of the Declaration was the official one at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. But this new handwritten manuscript from America’s tumultuous 1780s was hidden in plain sight the whole time.

The document was discovered by Emily Sneff, the research manager of Harvard’s Declaration Resources Project, and Danielle Allen, a political theorist at Harvard University, and has a few key differences from the original, particularly the order of the signatures.

It was also found in England. Its existence surfaced three major questions about America’s history and the writing of the Constitution.

Allen laid them out to the Harvard Gazette:

“One is: Can we date this parchment based on the material evidence? Second: Who commissioned it, and why? And third: How did it get to England?”

Sneff discovered the copy in the West Sussex Record Office while browsing through the archives. Although there are a number of copies of the Declaration, most are reproductions of the original version from the National Archives that were published in newspapers. The Sussex version was odd because it was on parchment and horizontally oriented. Sneff also noticed that the signatures were in a different order, that the punctuation was different, and the handwriting was not the same as the original.

The Sussex Declaration.

Dating the Parchment

The first step to figuring out if the copy was real was to date the parchment. In a paper in final revisions for the Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, Allen and Sneff analyzed the parchment in a few ways to suggest that the copy was made in the 1780s, very close to the time of the signing of the original Declaration.

Detail of the "Pursuit of Happiness" on the Sussex Declaration.

To do this they compared the penmanship of the document, the ceremonial formatting, and the preparation of the parchment to other historical documents. The misspellings in the signatures on the copy, due to having to decipher them from the original signatures on the Declaration instead of a printed list, were the final confirmation for the 1780s date.

Why It Was Made

One of the major differences in the new copy of the Declaration is that the signatures along the bottom are in a totally different order than on the National Archives version. Allen and Sneff point out that between 1776-1791 the names of the signers were not stable, and some people, like Thomas McKean, were added after the original signing.

Detail of the List of Signers on the Sussex Declaration.

Instead of following the order of the original Declaration, the Sussex Declaration puts the names in an order based on a cipher specifically designed to keep the names from being grouped by state. Allen and Sneff argue that the deliberate re-ordering suggests that the commissioner was James Wilson of Pennsylvania, one of the original signers and a strong nationalist who became one of the first Supreme Court Justices. This argument was presented at a Yale University conference on Friday.

How It Got to England

Although Sneff and Allen haven’t written a paper on how the copy made its way to England, their current hypothesis is that it made its way to Charles Lennox, the third Duke of Richmond. Lennox was a major supporter of American independence, and his papers are collected at the West Sussex Records Office. Exactly how that may have happened though, is still a mystery.