This Astronomer Just Said Old Tech Will Find the Next Earth

On Thursday, astronomers and astrophysicists gathered at Stanford University for the Breakthrough Discuss Conference to share research on topics that lived in the realm of science fiction until very recently: the search for Earth-like planets outside our solar system.

Key to finding Earth-like planets will be leveraging older technologies in more novel ways moving forward.

The symposium is sponsored by Breakthrough Initiatives, whose board boasts Stephen Hawking, Yuri Milner, and Mark Zuckerberg. Breakthrough Initiatives, you may remember, is the same group behind the Breakthrough Starshot plan to send a swarm of tiny robots over four light-years away to )[Alpha Centauri](https://www.inverse.com/topic/alpha-centauri — the closest neighboring star system to us at just 4.3 light-years away.

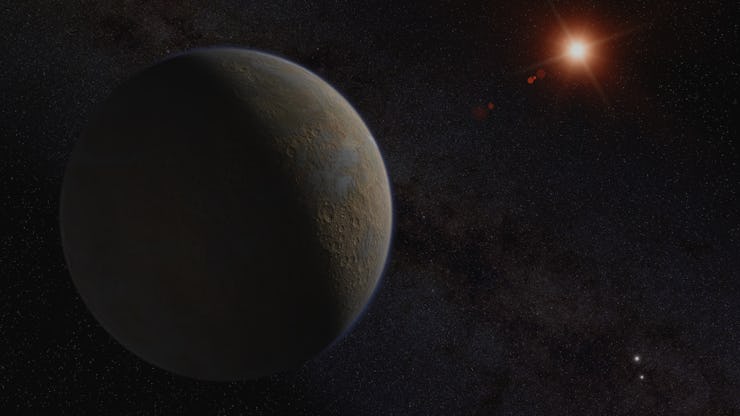

The event kicked off with a keynote address by Queen Mary University of London astronomer Guillem Anglada-Escudé, who took the stage to discuss, among other things, why red dwarf stars like nearby Proxima Centauri (at 4.25 light-years away, with its own rocky exoplanet, Proxima b) are so likely to host habitable planets. Part of the reason: There are a ton of these so-called M dwarfs.

This is a remarkable tone for a scientific conference.

It’s not too surprising, though, considering how quickly things have moved over the past year. Mere months after the Starshot Breakthrough plan was announced in April 2016, scientists discovered Proxima b in August 2016. This small planet lies within the habitable zone orbiting Proxima Centauri.

And even for an event predicated on exceptional scientific advances, one of Anglada-Escudé’s big points is an exceptional one: Scientists are getting even better at finding exoplanets. In fact, he explains that the technology to discover nearby planets has existed for years.

“The instruments that we were using in 2010 are the same as in 2002,” he says.

The primary obstacles were in developing a plan to apply these instruments, and deciding where to look.

“This could have happened in 2002,” says Anglada-Escudé. “What happened is that we didn’t know what to expect. At the beginning it was like fishing, like going into the forest and searching for something.”

These advances are just what Breakthrough Initiatives seeks to foster. The organization’s goals are to find extraterrestrial life and go to it. This is no small task. But the group, funded by Milner and backed by Hawking and Zuckerberg, has the resources to help make it a reality.

Guillem Anglada-Escudé explains that, if the pizza is Jupiter's orbit, then Alpha Centauri is way off in the distance.

As astronomers continue to better understand how to use available telescopes to efficiently search for planets, the search for intergalactic life becomes less and less far-fetched each year. Last year’s ambition is this year’s commonplace.

Even so, the ambition is monumental. Studying Proxima b is nothing like studying Mars.

“It’s 3 orders of magnitude farther away than anything we have tried before,” Anglada-Escudé reminds the gathered researchers. “This is not about a longer stroll. This is a completely different story”

This fits with changing attitudes about how to look for exoplanets. Anglada-Escudé points out that, since red dwarfs are so likely to host habitable planets, in the last few years, astronomers have realized that looking at stars one by one is not a waste of time.

“Detecting planets around red dwarfs, because they are smaller, is up to 100 times easier,” he says. This is the take-home message of 2016’s dicovery of Proxima b. Now we can search star-by-star.

So how do astronomers look for a planet orbiting a distant star? One major way is a technique called transit photometry. This involves measuring how the light coming from a star changes as the planet passes in front of it. In this way, researchers can establish a planet’s orbital period and size.

Transit photometry allows astronomers to find out how big a distant planet is and how long its orbital period is by measuring how much light it blocks from its star and for how long.

The problem with this technique is that planets need to be aligned to our line of sight. According to Anglada-Escudé, 98 percent of exoplanets will be hiding in some weird orbit and therefore won’t be measurable by transit photometry. This necessitates some creative use of existing technologies, such as high-contrast direct imaging and spectral enhancement.

But still, even once you find evidence of a planet, that doesn’t mean much until you prove it.

“If you really want to confirm that something is a planet, you need to put together an experiment to prove it or rule it out,” says Anglada-Escudé. And that’s one of the important takeaways from this presentation: Science only yields flashy results because scientists take the time and energy to bury their heads in the data. Fortunately, lots of people who have pulled something incredible from the data are gathered at the Breakthrough Discuss Conference to share their results. And though Hawking, Milner, and Zuckerberg have their hands in this conference, the range of astronomers involved encompasses so much more than just them.

You can watch the rest of the Breakthrough Discuss Conference live on Facebook.