What's Up With John B. McLemore's 'Titty Rings' and Tattoos?

We asked a psychological expert.

John B. McLemore — the eccentric clockmaker who disdainfully referred to his hometown of Bibb County in rural Alabama as “Shit Town” — is the star of the hit podcast S-Town. Through the course of seven episodes, host Brian Reed delves into the remarkable, complex life of McLemore, who is depressed, rants on about climate change for hours on end, and boasts a surprising array of disturbing tattoos and a pair of nipple piercings.

It’s not until the final episode that Reed describes McLemore’s Sunday ritual, which McLemore calls “church.” McLemore’s tongue-in-cheek “church” ritual involved close friend/surrogate son/potential gold-snatcher Tyler Goodson helping McLemore injure himself. This involved multiple re-piercings of his nipples, and at least one incident of McLemore asking Goodson to whip him on the back multiple times, then tattoo the lash marks. McLemore also asked to get tattooed repeatedly without ink, the ostensible purpose of which was to simply feel the pain of the needle enter and exit the epidermis.

So was McLemore a sucker for masochism — or was his pursuit of extreme pain a psychological cry for help? Rolling Stone’s Elizabeth Yuko has suggested that McLemore was seeking an informal method of pain therapy or even practicing BDSM, but even that brings up the question of whether McLemore was somehow seeking to supplant what turns out to be a lifetime of deep, emotional pain into some physical manifestation.

Janis Whitlock is the director of the Research Program on Self-Injury and Recovery at Cornell University. She hasn’t heard S-Town, but she says that the eagerness McLemore shows to self-flagellate, experience increasingly potent forms of pain, and find solace in it are not uncommon among those who self-injure — particularly among suicidal males who feel socially isolated, like McLemore.

Whitlock cites research done by her colleague at Cornell, Joe Franklin, that suggests that what a person who self-injures repeatedly is actually seeking is not the immediate pain that comes with harming oneself but pain offset or the ebbing dull pain that follows injury, “instead going far beyond the previous point into a more pleasant feeling often labeled as ‘relief,’” Franklin writes.

“Essentially, the neurological network in the brain area that regulates perceived rejection from society and interpersonal relationships [are the same],” Whitlock says. The regions in the brain are the anterior cingulate cortex and the anterior insula, areas of the brain that interact with each other to dictate not only decision making but complex emotional responses. In particular, however, the network between these two sections of the brain are key to how a person comprehends the emotional effect of pain rather than the physical effect of pain.

It’s this emotional understanding of pain that Whitlock says we’re still trying to understand, equating our body’s digestion of the emotional and physical aspects of pain to becoming “our own walking pharmacies.”

“There’s an engagement of the endogenous opioid system that makes us all walking pharmacies [when we experience physical pain],” Whitlock explains. “We all self-regulate, and some of us know how to trigger the euphoria after self-jury for the offset.”

The offset is really what frequent self-harmers like McLemore are chasing after, and Whitlock says it’s a lot more complex than seeking a physical substitute for psychological pain. She points to early research done by Arizona State University psychologist Nancy Eisenberg that shows the axiom “sticks and stones can break my bones, but words can never hurt me” to be simply untrue. Eisenberg found that areas of the brain of the emotionally wounded lit up more when feelings were hurt than when there was a physical perception of being hurt. It proved that the emotional conception of pain had a stronger effect on humans than physical pain, and that what McLemore was potentially trying to attain was some sense of empathy for his own pain.

McLemore also fits into the demographic of self-injurers. Again, Whitlock hadn’t heard S-Town prior to being interviewed, but her description of the traditional self-injurer could double as a description of McLemore: male, depressed to the point of suicidal tendencies, emotionally fragile yet possessing a strain of bravado when it comes to pain.

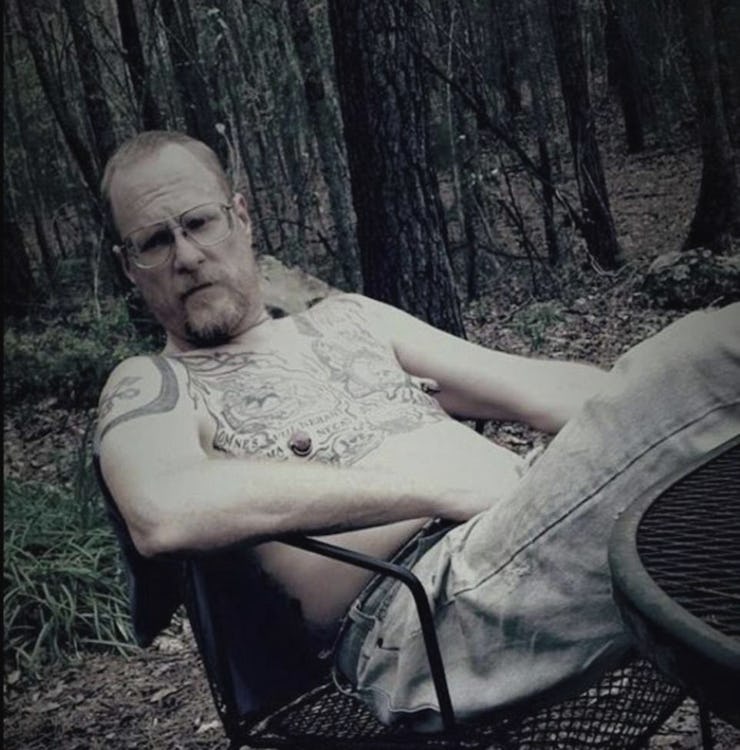

The lashed/tattooed back of John B. McLemore

Importantly, self-injurers report harming themselves to get some control over their pain, emotional or otherwise. “There’s a strong correlation between self-injurers and trauma or abuse history,” Whitlock says. “These people are temperamentally wired to perceive pain more acutely. They’re emotionally perceptive and able to experience the world more subjectively than others. That’s why they rely on the pain offset — it’s a way for them to experience pain that’s more acute and intense.” Remember McLemore’s passionate rants about climate change, his frustration that people simply didn’t care about the same things that he did that often broke into hysterics, laughing, and eventually, sobbing?

While Whitlock isn’t aware of any literature on tattooing over whiplash marks or repeated nipple piercings, she says that McLemore exhibits signs that probably indicate that he is a self-injurer — and that he liked it. On the podcast, Goodson goes so far as to tell Reed that he thinks McLemore was addicted to the pain of tattooing. “He got enough tattoos in one year that someone could get in a lifetime all at once,” Goodson drawls. “He got addicted fast.”

Whitlock isn’t against describing McLemore’s pursuit of pain as an “addiction,” though she says one must be cautious about the terminology. “Addiction is traditionally defined as the introduction of an external substance that a person become habituated to,” she explains. “But we’re all walking pharmacy factories, and we can become attached to the production of a feeling — in which case, self-injury is definitely something that we can become addicted to. The chemicals secreted in our brain can be something ‘addictive,’ and we can try to chase that feeling.”