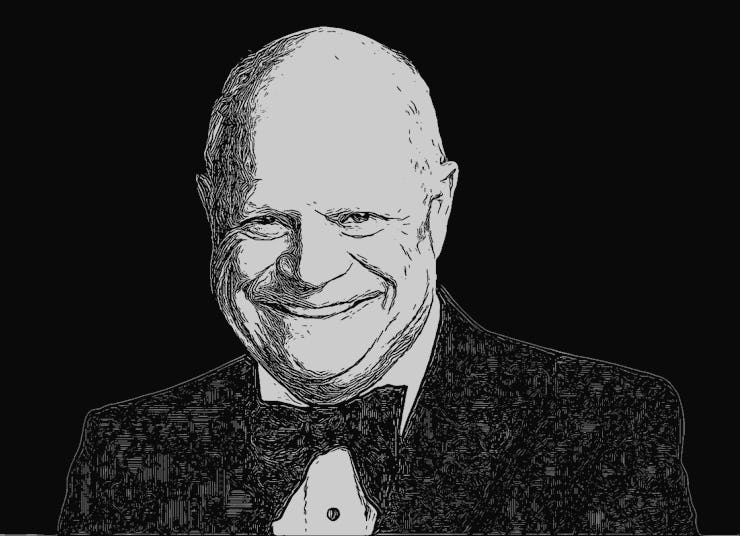

Last week, legendary comedian Don Rickles died of kidney failure at the age of 90. Many went online to mourn the legendary insult comic; on Twitter and Facebook, both fans and those close to Rickles celebrated his brash style and take-no-prisoners approach to comedy.

Why does the passing of a comedian like Rickles hit some people especially hard in the feels? Outpourings of grief were similar at the deaths of John Belushi, John Candy, George Carlin, Chris Farley, Greg Giraldo, Mitch Hedburg, Bill Hicks, Andy Kaufman, Sam Kinnison, Phil Hartman, Bernie Mac, Patrice O’Neal, Gilda Radner, Gene Wilder, and Robin Williams, among others.

Inverse asked psychologist Dr. Robin Hornstein about the process of mourning celebrity deaths, and she offered up three theories explaining why we grieve so intensely even when we don’t personally know the person who died.

A Strong Sense of Empathy

Hornstein says that a particular closeness to a celebrity’s death may stem from an empathetic connection a person has made to the celebrity. Enjoying someone’s skill — like Rickles’s comedy — we get a glimpse of what it might feel to actually be them.

This theory is supported by studies on empathy as it connects to sports and the performing arts, which suggest that observing someone’s actions — or even just imagining other’s actions — prompts a matching neural and autonomic state in the viewer. This is thought to be especially common when people watch other humans in motion — like seeing a baseball player on the field or a standup comic moving across the stage — because of the bidirectional link between perception and action in the brain.

Disenfranchised Grief

“Disenfranchised grief” is a term for grief that isn’t socially sanctioned, openly acknowledged, or publicly understood. In other words, it’s the sense of grief that also makes you feel uneasy because you’re unsure whether society will accept that grief as valid. If a person mourns a celebrity they don’t know, and questions their right to grieve, that’s disenfranchised grief.

But society’s questioning doesn’t make this grief any less real.

“We fall in love with the story, beauty, humor, and creativity of others,” says Hornstein. “Are we allowed ‘miss’ Bowie or Prince? I would say yes, because they hold a certain meaning of us.”

Rickles’s importance to his fans, Hornstein reasons, may be rooted in his mission to make us laugh at ourselves and his ability to connect to others as a “regular guy.”

“We wanted to be Rickles, but be wanted by someone like Bowie,” Hornstein says, distinguishing between the emotional processing of both deaths.

Representational Loss

“Rickles is the loss of the elderly cohort, or for others, their parent or grandparent,” Hornstein explains. “Thus representational loss is hard to handle because many people want to deny the truth of impending death.”

The way Rickles was publicly mourned illustrates her point perfectly; in the days following his death, many people (including celebrities) testified that his loss was harder to deal with because of the influence he had as a prominent comedian.

Rickles also represents a specific period of time, Hornstein explains, and mourning for him could also indicate an acknowledgement of the end of a cultural era.

“Rickles, like all language-based performers, was set in a time period,” says Hornstein. “His humor was sexist by today’s standards, but it fit into the culture he appealed to at the time — mostly white, traditional, and working or middle class — and it worked.”