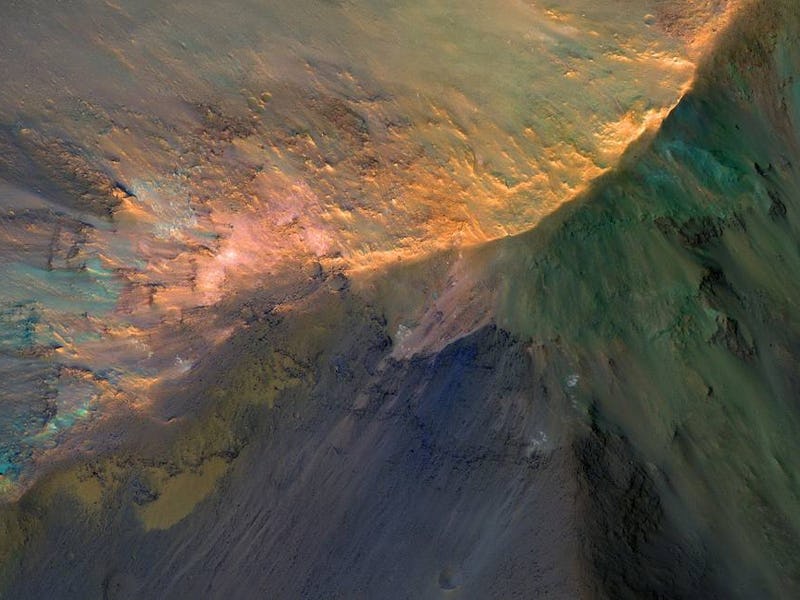

In the northern region of the vast Valles Marineris canyon system on Mars lies the Juventae Chasma — a series of sandy hills that can reach peaks of more than 3,000 feet high. In a new image taken by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), some rebellious sand dunes from the canyon floor are seen scaling the hills.

The orbiter’s mission is to take extreme close-up shots of the Martian landscape to study the mineral composition and trace the surface for any signs of water. In this image of the sun-soaked and sandy swept hills, MRO shows that the red planet is not so red after all. Although the image is color-enhanced, it’s the diverse minerals embedded into the surface that is thought to primarily account for the incredible variety of shades and tones streaked across the canyon.

The exact mineral composition of the Valles Marineris canyons is not entirely known, but scientists believe it once was a region of intense volcanic activity and may have even contained an ancient ocean or lake, which would explain the diversity in colors.

The sandy hills of the Juventae Chasma.

Valles Marineris completely dwarfs the Earth’s Grand Canyon. In fact, at 2,500 miles wide, it is larger than the entire United States and takes up 20 percent of the surface of Mars. In this image, you can see the sheer size of Valles Marineris, which lies along the planet’s equator.

The Valles Marineris canyon system takes up 20 percent of the surface of Mars.

There is perhaps no better place on the red planet to dream about the history of life on Mars. In September 2015, when scientists announced the discovery of liquid water on Mars, the Valles Marineris was the point of focus. When evidence of transient water flows called “recurring slope lineae” were found in the region, scientists became obsessed. A study published in July 2016 stated there was enough water in the region to fill 10 to 40 Olympic-size swimming pools.

“The occurrence of recurring slope lineae in these canyons is much more widespread than previously recognized,” said the University of Arizona planetary researcher Matthew Chojnacki in a statement. “As far as we can tell, this is the densest population of them on the planet, so if they are indeed associated with contemporary aqueous activity, that makes this canyon system an even more interesting area than it is just from the spectacular geology alone.”

With flowing water, sand dunes, volcanoes, and more, the Valles Marineris will no doubt be one of the first regions astronauts study when humans finally land there in 2033.