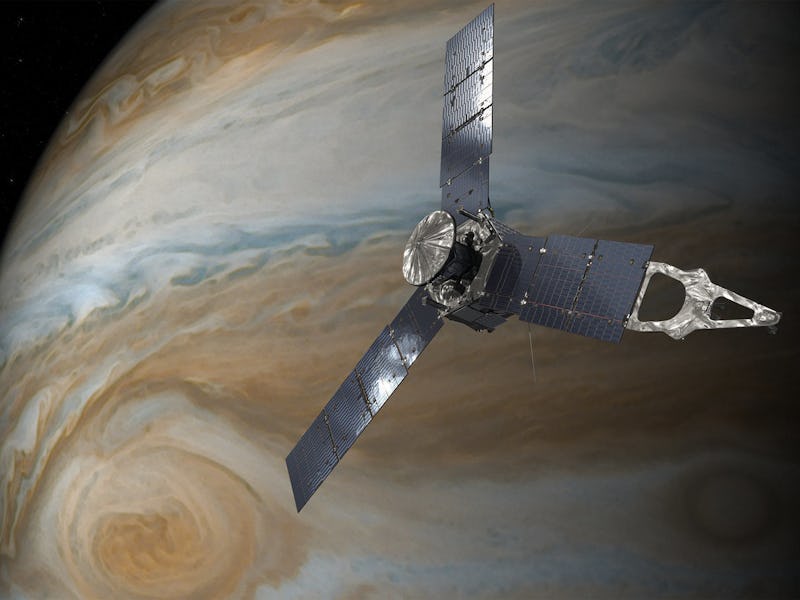

NASA caught a glimpse of Jupiter on Monday, as its Juno orbiter passed the red planet at 4.52 a.m. EST. The spacecraft, moving past the planet for its fifth time, has been collecting data since it entered Jupiter’s orbit in July 2016, after lifting off from Florida’s Cape Canaveral launch complex in August 2011.

“This will be our fourth science pass — the fifth close flyby of Jupiter of the mission — and we are excited to see what new discoveries Juno will reveal,” Scott Bolton, principal investigator of Juno from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, said in a statement released Friday. “Every time we get near Jupiter’s cloud tops, we learn new insights that help us understand this amazing giant planet.”

During the passing, Juno had its eight instruments switched on and collecting data from 2,700 miles above the clouds, moving at 129,000 miles per hour. In other orbits, the satellite has reached as low as 2,600 miles above the clouds.

The mission is aimed at learning more about Jupiter’s origins and structure. Probing below the clouds, the satellite is designed to find out more about the planet’s atmosphere and magnetosphere. So far, the team has discovered that Jupiter has complicated magnetic fields, and that the unique cloud tops extend well below the surface into the gas giant’s interior.

Each of the satellite’s five orbits last for 53 days, but NASA originally intended for only the first two orbits to last for that long. After that, the plan was to switch on Juno’s engines and move the satellite closer to Jupiter, meaning more frequent 14-day orbits that should lead to larger collections of data.

Unfortunately, during a check of the internal systems, the agency found that the helium check valves were taking several minutes to open when they should have taken just a few seconds.

“During a thorough review, we looked at multiple scenarios that would place Juno in a shorter-period orbit, but there was concern that another main engine burn could result in a less-than-desirable orbit,” said Rick Nybakken, Juno project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “The bottom line is a burn represented a risk to completion of Juno’s science objectives.”

Instead of undertaking a risky firing that could have put the whole mission at risk, NASA decided to stay at the 53-day orbit levels. The agency has justified it by claiming that they will receive “bonus science” from the repeated passings, which is possibly true, but it’s not quite the exciting information the team could have collected from closer passings.