Why Ben Affleck's Batman Spurred Hans Zimmer to Quit Superheroes

"I didn’t feel the pain that I felt in Christian’s performance."

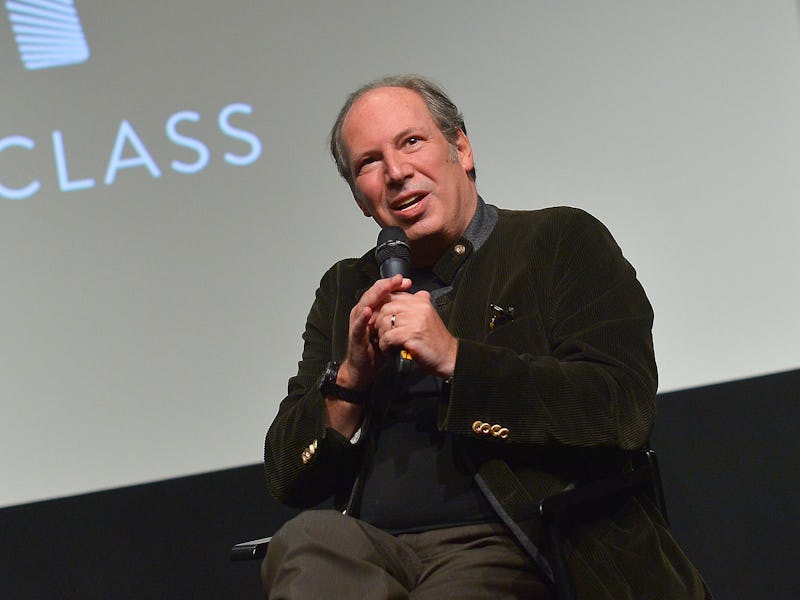

Hans Zimmer is as prolific as he is innovative. The 59-year-old German composer began his career playing in bands, transitioned to advertising jingles, and moved on to movies in the late ‘80s. A lucky break led to work on Rain Man, and since writing the score for Barry Levinson’s Oscar-winning drama, Zimmer has written music for over 150 films in just under 30 years.

Zimmer’s accomplishments — which include an Academy Award for his score on The Lion King — are even more impressive when you consider that he received all of two weeks of formal musical training. And to this day, even after scoring huge hits like the Dark Knight trilogy, 12 Years a Slave and Gladiator, Zimmer likes to joke about his unconventional arrival in the industry.

“Backdraft was the first movie where somebody let me loose with a huge orchestra, and I didn’t really know what to do with them,” Zimmer admitted in an interview with Inverse this week. “I had overheard the producer say that the composer on Ron Howard’s previous movie had used 101 people on the orchestra, so I booked 101 players, because I thought that’s what you should do.”

The composer definitely figured out what to do with all those musicians in the subsequent two decades, and he’s now offering up his expertise to aspiring musicians in a new MasterClass, available online now. Zimmer spoke with Inverse about becoming a teacher, his embrace of technology, and why he retired from superhero movies.

How did the way you learned influence the way you teach people through MasterClass?

One of the things that seems to get lost a lot in teaching music is when you have a band in a room and we start playing together, the main thing is we’re listening to each other. Because that’s the only way we can go and make the other person sound great. You figure out how to support them. And you really quickly figure out how, when somebody plays a C, you just know it’s a C. You don’t have to have perfect pitch, you train yourself to have relative pitch. You know what sounds good and what doesn’t sound good.

The other side of this was, when I was growing up, it was just the time when technology started to come around. Friends of mine were playing with their little processors, and I thought, this is really interesting, I could go and pervert this new technology to become a musical instrument. So I got into electronic music and all that stuff. People forget that every musical instrument is a piece of technology of its time. Violin is about as cool a piece of technology from the 16th century as you can get. And when you get to the church organ — this is the stuff I learned on Interstellar — the church organ is the most complicated piece of technology of its day. And it didn’t actually get beaten as far as technological complexity goes until the telephone exchange. By the 17th century, we already had these amazing pieces of technology at the service of art and music.

Then something happened where people were going, “Oh, synthesizers are not instruments. Electronics aren’t music.” And now everybody’s working on their laptop and making music on their laptop. I’m not saying I was ahead of the curve because I was smart, I was ahead of the curve just because I didn’t want to go and have piano lessons.

You said last year that you were retiring from scoring superhero movies. How’s that going, and why did you decide to do it?

Well the retirement is going pretty well because I’m not doing a superhero movie; I’m working on something completely different with Chris Nolan. I’m also going on tour because all my musician friends said to me, “Time to stop hiding behind the screen. Time to actually look the audience in the eye. Time to do things in real time.”

I keep thinking about new styles of music and new ways of using technology, new ways of figuring out how to make everything that we do an experience for other people. And I just couldn’t do it anymore with the superhero movies, it’s as simple as that. If you take the three Chris Nolan Batmans, that’s three movies to you, but to you and Chris, it was 12 years of our lives. So sometimes you just have to say, “I don’t know where I’m heading, but I’m going to jump off this cliff.” As soon as I said it, there were a lot of phone calls coming my way going, “Are you crazy?” But I’ve never written music for money; money isn’t inspiring. And I didn’t want to get into it where it became a job.

Ron Howard actually said something very smart to me. He said, “Don’t say you will never do a superhero movie again. Wait for somebody to turn up with an amazing script for a superhero movie.” And I suppose that’s what I’m saying: Can I please have the amazing script?

It just did my brain in to have written Christian Bale as Batman, and suddenly it’s Ben Affleck [in Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice]. And it felt like I was betraying everything Christian had done. So there’s a certain amount of loyalty attached to those movies, as well.

It’s interesting that the actor changes the way you do the music when it’s the same character but a different person under the cape and cowl.

I spent months trying to come up with something for Ben. The Batman that I know and the one I learned is the one that Christian did, and Ben plays it differently. And I can’t quite shake that off. For me, the Christian Bale character was always completely unresolved. It was always about that moment at the beginning of the first movie, where he sees his parents getting killed. It was basically arrested development. The Ben character is more middle-aged; he seems to be grumpy as hell, but I didn’t feel the pain that I felt in Christian’s performance. And it was that pain that made me interested.

So you handed Batman off to Junkie XL?

Well … nearly. We did it together. Well, you know, honestly, thinking about it, we really did do it together. And it was great having a partner in crime on this thing. And you can’t have a better partner than Junkie. The guy is on fire constantly. He’s one of the most creative people I know, and plus, he’s as geeky as me.

What do you think the next big trend in movie composing will be?

I think the next big trend — and it really is happening already — is just people writing far more individualistic scores and breaking new ground constantly. If you listen to people like Johan Johansson, the borders between film music and popular music and classical music, all those walls are just coming down. And the walls between technology and people who went to music academy as opposed to people who are just incredibly passionate about music, all those walls are coming down. Look at what Johnny Greenwood is scoring. He’s in Radiohead, but he’s one of the greatest film composers out there. He’s a composer-in-residence at the BBC. There’s a guy who is comfortable in all fields.

Are filmmakers getting more comfortable letting composers experiment?

I think the good filmmakers always did. There’s that famous story of Hitchcock and Bernard Herrmann in Psycho. He only gave him one rule: The shower scene must have no music, otherwise you can do what you want. So, of course, the first thing Herman did was wrote an amazing thing for the shower scene. Music is inherently indefensible. If I play you a piece of music, and you don’t like it, I can’t explain to you why you should like it; it makes no sense. Herrmann took a risk with a very volatile director, writing that piece, and obviously, Hitchcock saw it and it was brilliant and he went “absolutely.” I think it’s always been a composer’s job to — in a funny way — not do what the director tells you to do because you’re supposed to listen to the subtext. People used to have the saying that we are supposed to serve the film, and I’ve used that myself, I said that many times. But really, the job is to go and enhance the film and bring something new to the table.

Looking back on your work, are there any scores or cues you would like to do over?

No, because otherwise you don’t move forward. I don’t watch them because I know that this is exactly what would happen. I’ll give you an example of something I’d love to do over: As Good As It Gets, the Jim Brooks movie. When we previewed it, there wasn’t music over the first scene, so people didn’t know it was a comedy. And Jack’s outrageous performance, like putting the dog down the garbage chute, all that stuff, you could just hear a collective jaw drop from the audience because they didn’t know if it was funny or just the most brutal thing they’d ever seen. And I put a little bit of music at the beginning, just to let them know it was a comedy, and I wish I hadn’t. It was great when it was unmitigatingly tough.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.