'Syndrome X' Explains How Benedict Cumberbatch Will Live to Be 400

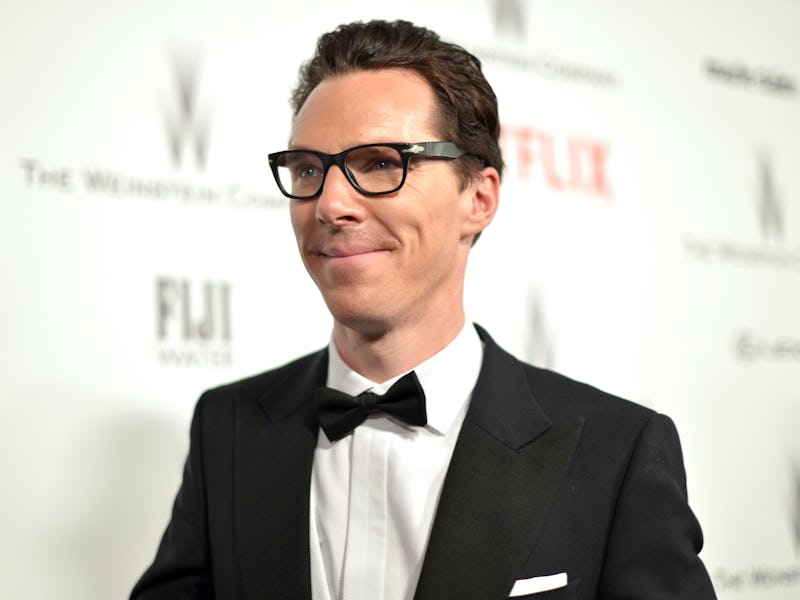

Strong acting chops and a malleable face have allowed Benedict Cumberbatch to play humans at various stages of life, but the Doctor Strange star’s newest role pushes the limits of age to their extreme: In How to Stop Time, he will play a 400-year-old man with a rare condition that slows down the aging process so that he looks only 41. While the film is based on a fiction novel, its premise is not: There really is a disease that slows aging to a crawl, and it’s known only as Syndrome X.

The synopsis for How to Stop Time, a novel by British author Matt Haig, describes its main character, Tom Hazard, like this: “He may look like an ordinary 41-year-old, but owing to a rare condition, he’s been alive for centuries.” As far as we can tell, the book doesn’t give that rare condition a name, but its effects are certainly similar to those of Syndrome X, a disease so rare that doctors haven’t been able to give it a real name.

The most famous Syndrome X case is Brooke Greenberg, a girl with the disease that was first profiled by Dateline in 2001. She weighed only 13 pounds and was 27 inches long when she was 12 years old. Richard Walker, the University of South Florida College of Medicine in Tampa scientist that studied Greenberg for years, noticed that she was indeed aging — just incredibly slowly. Describing Greenberg, he wrote, “She is not simply ‘frozen in time’. Her development is continuing, albeit in a disorganized fashion.” The Guardian reported on a similar case in 2014, describing an unexpectedly small 9-year-old girl named Gabby Williams who was also developing at a very slow rate and had the “hazy awareness of a newborn.” So little is known about the syndrome that it is unclear whether the two girls have the same disease.

Scientists who have studied Syndrome X assume its cause is genetic. Previous research had identified genes that were associated with premature aging, so researchers questioned whether Greenberg’s syndrome might have been caused by mutations in these genes that caused their function to be absent or reverse? In 2009, a team of scientists led by Walker that analyzed Greenberg’s genes discovered that this simply wasn’t the case — those genes remained normal — but their observations led them to hypothesize that there was a “master gene” to control aging — a gene that Greenberg and Williams might lack.

Though Greenberg passed away in 2013 at the age of 20, analysis on her genes continues in hopes that they will reveal what the fundamental driver of aging really is. Figuring that out will, hopefully, help scientists decide once and for all whether aging is simply a natural process — or whether it’s a disease to be cured. In the meantime, the condition she seems to share with Williams will continue to fuel human fantasies of beating aging — whether by slowing it down or eliminating it entirely.