Zach Gage, 'Really Bad Chess,' and the Expressive Power of Games

The 'Really Bad Chess' designer explains his philosophy on creating games.

Game developer Zach Gage’s art is entwined in his games, and his games ebb into his art in a seamless back and forth that has been customary for his entire life. Growing up with a family of artists, Gage wasn’t allowed to own video games of his own unless he made them himself — his mother even set him up with rudimentary software that helped him create games up through high school (while Gage discreetly snuck off to friends’ houses on occasion to play their enviable game systems). After graduating college with a degree in art, he put his software design experience to work creating interactive concept art. But his life changed when he discovered the Wild West that is the App Store alongside the birth of the iPhone in 2008.

Disappointed with early versions of Tetris on the App Store, Gage opted to create his own, Unify. “I put it out, and people were into it, and on a lark I went to IndieCade,” Gage says. “I met all of these amazing people who were making games and who had somehow heard of Unify and heard of this art game I made, Lose/Lose, and I was just so blown away that this amazing community was out there, and that they knew my work, and so I kind of have been making games ever since.”

Gage's first game, 'Unify'

Gage has since gone on to build an impressive portfolio of work on indie mobile games, including SpellTower, Really Bad Chess, and collaborative work on Ridiculous Fishing, titles which gained a lot of critical attention for their clever design. Yet his games have also reached outside the fairly insular gaming-sphere to appeal to those from all walks of life. That stems from a deliberate effort on Gage’s part to ensure his games have broad appeal.

“There are some small things that I do in every game,” he continues. “I always try to provide a lot of different modes, because people are always looking for different kinds of things. You have people who want to compete, you have people who just want to casually do something and be able to take out their phone and do it. You have people who like time pressure and people who don’t like time pressure. So that’s sort of the small end of the stuff that I try to do to accommodate people.”

'SpellTower' was Gage's first App Store hit.

Through a wider lens, though, Gage wants his games to be accessible, because, like art, he feels that video games are a medium that has the potential to engage society and get people thinking about their own world, and not just the one they’re visiting.

“When I make games, I really feel like they’re an extension of my art practice,” Gage admits, “and so all of the art that I do is really rooted in this idea of trying to get people more critically engaged with the world around them.”

Critical thinking is an inherent, though often rarely practiced, human skill that video games are uniquely equipped to exercise. Playing interactive, cerebral games like Portal or The Witness get you to think in ways you didn’t even know you could, and thus begins a slow addictive drip of critical thought morphine that leads you ever onward. In theory, anyway.

'The Witness' is well-known for its tough puzzles that force players to stretch their brains.

Gage takes a similar approach to these popular games. “I really try to build games that encourage critical thought. And usually I try to make games that seem like they’re easy to get into, but then as you play them, hopefully they sort of push you to critically engage with them and come up with strategies and find new things.”

It’s Gage’s hope that people will take the skills they develop in video games and carry them into other places in life. It’s easier to do this nowadays, thanks largely in part to mobile and social games, as more people have access to games than ever before. “All kinds of people are starting to play them,” Gage notes. “That’s the conversation I want to have. I don’t really want to have an insular conversation about, you know, ‘Here’s a new twist on a Metroidvania.’ I want to make games that are super broad and appealing and can get that sort of critical thinking happening on a wider scale.”

There are some difficulties in bringing games to larger audiences, however. Video games have developed a very specific literacy that is difficult for people who aren’t well-versed in the gaming space. Someone who’s never played a game before won’t know how to react to certain video game situations that a more seasoned player can easily parse. Video game logic does not necessarily equate to real life.

Board games go way back. 'Senet' is an ancient Egyptian board game.

But video games have also developed out of an ages-long literacy of board games, card games, and simply play in general. “When you look at video game design, there are really two histories,” Gage explains. As it happens, video game design stems from a much broader design history.

“This history is from the entire history of human civilization interacting with games. How does it feel when you lose a bunch of physical objects? How do dice work? How do we understand cards? That has its own set of literacies and intuitions,” Gage argues. “So for me, even if I’m not necessarily using specific components like playing cards or chess pieces, I’m generally reacting to the literacy that comes from the physical world.”

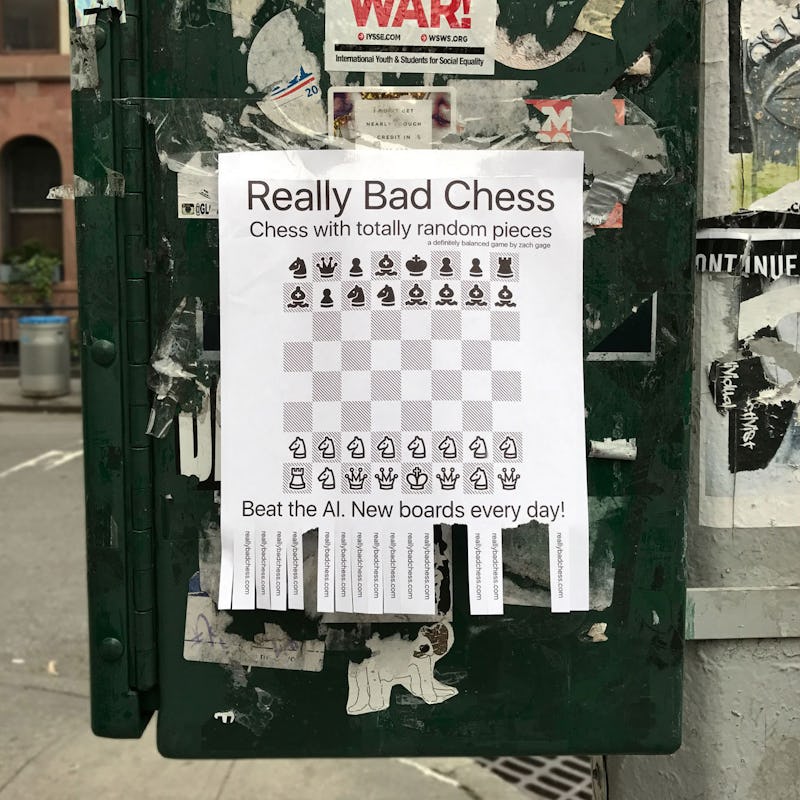

Those sorts of mechanics haven’t been explored broadly in games, but Gage believes that there is a lot of room for video games to grow in that space. Video games need to go back to their roots. They’re capable of exploring mechanical elements, like dice rolling or physical game pieces, from that part of their history in a way that analog games cannot. Gage cites his game Really Bad Chess as an example. The game assigns you a random allotment of chess pieces that may not make sense at first.

'Really Bad Chess' has a blatant disregard for the traditional rules, and it's delightful.

“Really Bad Chess is a modification [of chess] that’s almost impossible to do if all you have is a physical chess board, because you have to buy four more physical chess boards, and not that many people have four identical physical chess boards,” Gage explains. “But in the digital space, it’s like, ‘Oh! Well we just change the pieces to whatever we want.’ And suddenly it’s this new game.”

This unique power that video games have extends beyond game theory and literacy. They also stand alone in other ways. Other artistic and literary mediums — books, music, fine art — provide experiences, but the way you think about those experiences is completely different.

“When you have a painting, a book, or a song, when you think about it, when you engage with it, read the book, look at the painting, or when you listen to the song, you’re having an experience,” Gage says. “But when you think back about the book, painting, or song, what you’re really doing is you’re thinking back to the object in most cases. You’re thinking about how the chords in the song work, what the words in the chorus are, what the painting looked like, or what the book said.”

'Eve Online' provide these sorts of experiences on a grand scale.

Games are capable of providing these sorts of experiences, certainly, but there’s a difference in the emergent experiences and stories only games can provide. When you look back on your experience with a game, you may remember the story and the character. But really, Gage suggests, you’re truly thinking back on what your own experience was and how you can improve on navigating that experience in the future.

“I think that’s really different than a lot of media,” Gage posits. “I think it’s really important, because when you deal with an experience, you’re communicating a lot more information than you necessarily would be communicating just with an image or a set of words, because an experience is something you continue to unpack as you think about it, whereas, you know, with music you will find new things, but often the relationship you found with it, the things that you connect it to when you first heard it, are the things that you connect it to forever.”

Video games provide ever evolving experiences. What you encounter in one playthrough of a game could be entirely different from the next. “When you look back at a video game, play again, or you think about a video game, sometimes you find a thing that wasn’t [what] you remember, or wasn’t the thing you were thinking about, and that makes them very holistic experiences.” Gage elaborates. “And that’s very different from the way that we interact with a lot of media.”

Zach Gage worked with NYSCI on the 'Connected Worlds' interactive exhibit.

These gamified experiences can have affecting, real-world applications. Gage recently worked on an interactive art project with the New York Hall of Science that teaches children about environmental sustainability. A large part of the project was to educate students about long loops — the idea that the consequences of humanity’s impact on the environment might not manifest themselves for many years. That makes sustainability a pretty tough topic to grasp, even for adults.

“So the idea with this project was to build a project that would allow kids to play with the environment in this big interactive space and get a feeling for what it means to have a long loop,” Gage explains. “So if you take all of the water and you feed all of the plants on your wall, and you’re having a great time, and then you turn around, and you see all these other walls and all the plants are dead and none of the kids have any water, they all come over to your wall.”

This interactive experience explains the problem in pure, simple terms. “That’s an experience about the reality of environmental usage that’s very difficult to explain,” Gage says. “And even if you did explain it, you have people bringing all of their own thoughts and feelings and baggage into that. But when you just give people that experience, instead they have fun.”

In other words, video games have the power to put you in a situation and force you to consider different perspectives. “I think when you often look at art, you’re looking through the lens, and you’re seeing something,” Gage clarifies. “But video games, because they traffic in experiences, are really giving you the whole lens. It’s a thrilling concept, and as video games continue to develop, we’ll be seeing this manifest in exciting new ways in the future.”

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.