Why Hasn't Trump Mentioned Big Data Firm Palantir?

The secretive tech company has been building a massive surveillance weapon for years.

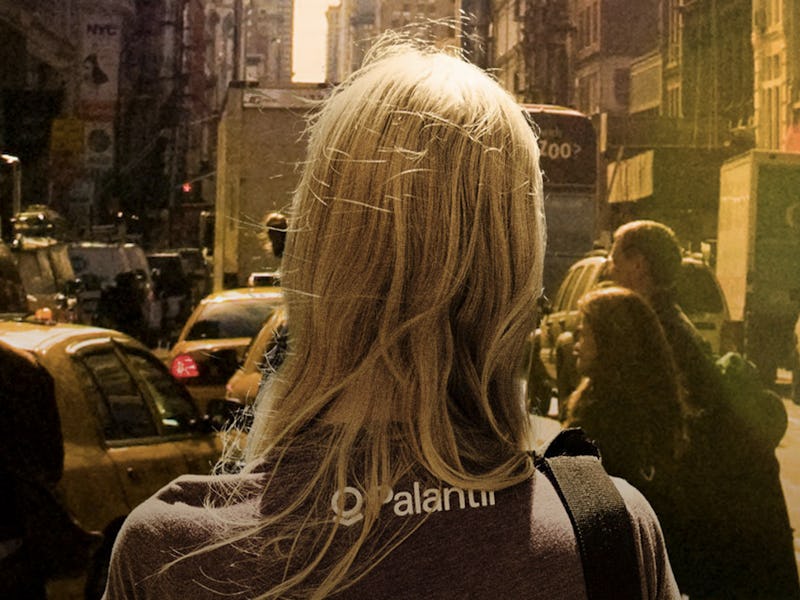

Even in secretive Silicon Valley, Palantir Technologies keeps a low profile. If you live outside northern California’s data-driven tech bubble, you might not have heard of the company, but it’s definitely heard of you.

Co-founded by Peter Thiel, Elon Musk’s brazenly Republican, Trump-supporting former BFF, Palantir Technologies collects data — mostly on people — and makes it easy for organizations to search for and analyze it. The CIA loves it, cops love it, other corporations love it, but surprisingly, President Donald Trump hasn’t mentioned it yet.

In January, two days before Trump was inaugurated, a group of around 50 tech employees and Silicon Valley residents huddled in the rain outside the Palantir Technologies headquarters in Palo Alto to protest the company’s involvement in the Analytic Framework for Intelligence (AFI), a program used by the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol department to track immigrants and travelers, would quickly run afoul of the civil liberties of American Citizens and foreign nationals visiting the country alike.

The protestors, many of whom came from Stanford University across the street, set up the “Do Better” campaign, a public petition for Palantir to take responsibility for the possible repercussions of its software — and unequivocally pledge to not use it to fulfill Trump’s campaign promise to create a registry of Muslims in America.

“Companies like Palantir sell themselves as ‘Big Data Analytics.’ That is, Palantir’s job is to take the large amount of surveillance data generated by the government and other companies, and organize it to provide answers to questions that their clients have,” Gilbert Bernstein, a Ph.D. student in Stanford’s Computer Science program and signatory of the Do Better pledge, tells Inverse. “Since their clients are mainly government agencies, this means that they organize information for DHS, ICE, and related agencies.”

The problem, protesters say, is that Palantir and other big data companies don’t like to take responsibility for what their clients do with all of that data-firepower. The Verge reports that Palantir’s AFI program amalgamates and analyzes massive amounts of data from local, state, and federal law enforcement databases — everything from fingerprints to tattoos and family information. The fear here is that centralizing that data will make it vastly easier to enact a system like Trump’s “extreme vetting,” or a registry on Muslims. If, for instance, a Muslim-American or undocumented immigrant gets booked for a minor crime and spends the night in a local lockup, their information, including identifying features and family contact info, could flow directly into a federal database tracking people like them.

“To put it differently, Palantir helps selectively enable the U.S. government to more efficiently and effectively detain and deport people,” Bernstein says. “They do not help people trying to stop deportations. And they make money in the process. As with IBM during WWII, the question isn’t so much about civil liberties being violated — the government does that. The question is about whether you’re helping grease the wheels of that machine, which Palantir absolutely is.”

According to a Politico report published in August 2016, Palantir has earned “at least $1.2 billion” in government contracts since 2009. Palantir CEO Alex Karp, a zany tech dude who favors neon clothing and travels everywhere with a 270-pound former-Marine bodyguard, told Forbes in January that the incoming Trump administration had not asked him to build a Muslim registry, and that, “if we were asked, we wouldn’t do it.” But for the 50 or so protesters willing to brave the rain six days later, that answer just wasn’t good enough.

“It’s farcical and terrifying that anyone should think that a declaration of ‘we would not do that’ is a sufficient guarantee about the application of a technology which, if/ when it is abused, will cause significant harm and morbidity,” says Ethan Li, a graduate student in Stanford’s CS department who also signed the pledge.

“Refer to the history of Japanese Americans and public health consequences for the Japanese American community for an illustration of what might happen,” Li says. “There need to be transparent accountability processes to outside stakeholders affected by the technology.”

Transparency, it seems, is the number one goal of Do Better. The protest’s signatories aren’t Luddites; the vast majority of them are tech workers or students. As the Intercept observed recently, the company has always been open about its intentions to market its services to the government.

Karp doesn’t shy away from discussing the trappings of his shadowy relationship with the intelligence community (he told Forbes the bodyguard is “a massive cramp” on his life because it “reduces [his] ability to flirt with someone;” but necessary because he says he receives death threats from extremists and is stalked by conspiracy theorists and schizophrenics), but he won’t discuss details of the contracts his company has been awarded.

The CIA’s venture capital firm, In-Q-Tel, was one of Palantir’s first investors. After a demonstration of some of Palantir’s capabilities in 2008, a classified British government report obtained by the Intercept noted that Palantir “has been developed closely internally with intelligence community users (unspecified, but likely to be the CIA given the funding).”

Trump now has a direct link to Palantir through Peter Theil, who currently serves as the Chairman of the company (it’s worth noting that the company itself is named after the shadowy crystal ball Saruman uses to communicate with the Dark Lord Sauron in the Lord of the Rings.)

Theil is a high-profile member of the Trump transition team, and as one of Trump’s only firm supporters in Silicon Valley surely has the president’s ear on technological issues. And all of this makes tech employees uneasy as hell.

“I believe information technology has the potential to facilitate massive improvements to the global standard of living by building systems that work to ensure more equitable distributions of resources (economic, natural, political, educational, health, etc),” says Alison Buki, a front end developer and designer based in D.C. who signed the Do Better pledge. “However, as history has shown — see IBM’s involvement in the Holocaust — too often these technologies are put to the service of oppressive regimes that seek to surveil, control, or in some cases eliminate specific populations for political purposes.”

In 2012, Palantir established the Council of Advisors on Privacy and Civil Liberties, a 12-member body of consultants, lawyers, and academics. The PCAP objective, according to Palantir, is to make sure the company lives up to its stated mission that “…in the world of data analysis, liberty does not have to be sacrificed to enhance security.”

Its website was last updated in January. Palantir did not respond to multiple requests from Inverse for comment.

So far, Trump hasn’t mentioned Palantir, or the AFI, or any of the software company’s wide-ranging capabilities. But as Palantir has proved in recent years, it doesn’t need recognition or a shout out from the bully pulpit to make money — it works best when it’s unseen.