This Low-Tech Device Is Primed for a Comeback

Business is booming at the dawn of the Trump era.

Cristina remembers the first time her ankle monitor talked at her. It spoke in Spanish.

From the surveillance device affixed to her ankle with a rubber medical grade strap came a man’s voice. “The monitor said, ‘you need to report to the ICE official,’” she tells Inverse through a translator, referring to Immigration and Customs Enforcement. “I called the ICE office and said, ‘I’m in court, they scheduled two meetings for the same time.’”

Cristina, who asked to have her last name withheld, was in the middle of an immigration hearing in San Antonio, Texas during this unsettling episode, back in May 2016.

She worried it could hurt her case, even though the disruption wasn’t her fault. Her attorney, Julie Sparks, remembers the incident well. “I was very upset. It was very unnerving, very disturbing,” Sparks says. “She was just about to start her testimony and I felt they were just harassing her.”

A disembodied voice coming from a device attached to one’s own body can seriously mess with anybody’s head, especially when under the stress that comes with an immigration hearing. “It got us off to a rocky start,” Sparks says. “It’s crazy, we’d be sitting there in a closed, confidential proceeding with her ankle talking to her.”

Bureaucracy was the reason. Cristina was double-booked because her judge decided to reschedule her hearing from morning to afternoon — when she was supposed to check in with ICE. “The court system does not communicate with the immigration-deportation official,” Sparks explains. “So they were expecting her to arrive following her [8 a.m.] hearing, and of course she did not, because it had been rescheduled.”

If her story sounds unbelievable, it shouldn’t. The official website for BI Incorporated, a wholly owned subsidiary of private prison company Geo Group, advertises a GPS monitoring device that allows officers to “send pre-recorded voice messages to offenders through the tracking unit, useful for appointment reminders or to notify an offender upon entering a forbidden zone.”

Every year, the United States detains between 380,000 and 442,000 immigrants, according to Community Initiatives for Visiting Immigrants in Confinement (CIVIC), which advocates for holistic community approaches to immigration as opposed to detention. In some cases, the detainees are held prior to deportation. In others, the immigrants are recent arrivals, sometimes in the process of applying for asylum. Immigrant detention, especially of women and children, became a hot topic in the summer of 2014, following an increase of refugees at the southern border, but then largely faded from public view (many were released in December 2016).

While executive orders already issued by President Donald Trump promised to establish more detention facilities, less attention has been paid to the issue of ankle shackles and continued monitoring while an immigrant’s case winds through the court system. It’s safe to say that by 2020, the end of Trump’s first term, the prison tech industry will be healthier than it’s ever been in history.

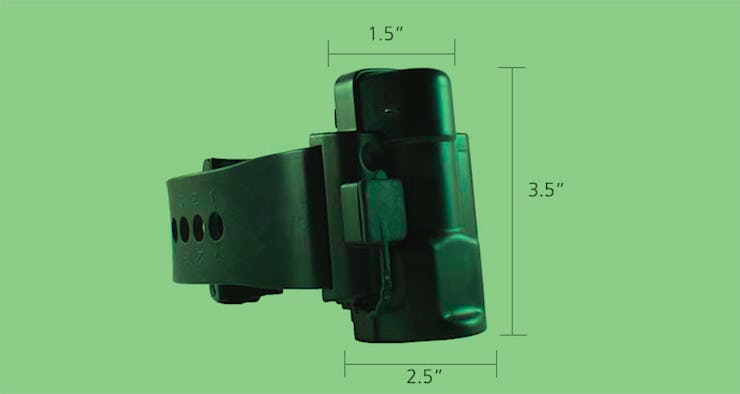

The ankle monitor offers "client communication" in Spanish and English.

Advocates for immigrants say there’s no question Geo Group is lobbying to push the government to expand its use of the electronic monitors, which are part of the Alternative to Detention program.

“They have the financial motivation to increase their capacity of these ankle shackles,” says Amy Fischer, policy director at the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services, an aid group based in San Antonio, Texas.

Pablo Paez, a Geo Group spokesperson, declined to comment on how many ankle monitors are currently in use, and instead directed Inverse to ICE, who did not respond to a request for comment. As of 2013, more than 40,000 immigrants had been enrolled in Alternative to Detention program, according to the Government Accountability Office. It’s not clear how many of them were forced to wear the monitors, and how many were given less restrictive release.

Cristina, 27, is from Guatemala and asked Inverse to use her real first name for this story because she is tired of living in the shadows. She lives in Texas now, and is one of tens of thousands of immigrants who have been issued ankle monitors made by corporations that make millions off of detaining and subsequently monitoring immigrants and asylum seekers. In addition to selling its ankle shackle product, Geo Group also operates a jail-like facility in Karnes, Texas — where Cristina was held. It’s one of three centers in the United States that house women and children fleeing violence, mostly from Central America.

The Karnes County Residential Center in Karnes City, Texas in a 2014 photo.

Cristina has been in the country for more than a year, wearing the monitor the entire time, except for one month. She says ICE took it off in June 2016, only to put it on the next month when she says they told her she was likely to lose her case, which could make her a flight risk.

Geo Group has set itself apart from other private prison companies by creating a way to monetize the entire cycle of immigration and asylum seekers, Fischer tells Inverse. In addition to the detention facilities and the ankle monitors, they also run a case management program that -– like the ankle shackles -– is billed as a detention alternative. “Their business model is much more diverse,” says Fischer. “They really have found this model of not only benefiting off of detention of immigrants but also of continued monitoring and surveillance of immigrants.”

Geo Group’s stock price plummeted following a Justice Department announcement in August that it would phase out the use of private prisons. Geo wasn’t alone. CoreCivic, formerly known as Corrections Corporation of America, is the other largest private prison company, which includes housing immigrants. It runs a family immigrant detention center in Dilley, Texas, as well as 73 other centers, reports the Washington Post, and also saw their stock value crash in August.

Then-candidate Donald Trump at the Phoenix Convention Center in July 2015 in Phoenix, Arizona. He spoke about illegal immigration about 4,000 people.

Under Trump, it’s been a different story. From November 8 to February 13, Geo’s stock increased by 86 percent, with no end in sight. CoreCivic also saw its stock price soar. “Trump presidency is providing a great opportunity to buy prison stocks,” advised MarketWatch in a story published on inauguration day.

“I do think we can do a lot of privatizations and private prisons,” then-candidate Trump said in March 2016. “It seems to work a lot better.” As is often the case, and frequently pointed out, Trump was either lying or didn’t know what he was talking about. A 2016 report from the Department of Justice’s Inspector General found that private prisons often perform poorly compared with public facilities, including “higher rates of assaults, both by inmates on other inmates and by inmates on staff.”

Geo Group’s argument in favor of the ankle shackles, which it calls monitors, is that it allows people in detention the option to be released to the community while still under control — and that it’s cheaper than holding someone in detention. “It’s supposed to be an alternative to detention, but in reality, it’s an alternative form of detention,” says Fischer.

Many of Fischer’s clients, primarily women with children seeking asylum in the United States, claim that they’re seen as criminals because of the stigma attached to wearing a shackle, or grillete, as her clients call them in Spanish. They also say that charging the batteries puts significant strains on their schedules, the devices can be prone to false positives, and that they’re painful and result in a tingling sensation of their feet.

An ankle shackle used to monitor immigrants who have been released from detention facilities.

Nighttime is the worst, in terms of pain, for Norma (not her real first name). She’s 26 and has only been in the United States for a few weeks. She lives in Santa Rosa, California, for now. A gang in El Salvador said they’d kill her if she didn’t give them money, so she, like thousands of other women, fled north, seeking asylum in the United States. After being held for two weeks in detention in Dilley, Texas, she was allowed entry into the United States. Prior to her release, ICE agents fitted her with a shackle. “My legs and feet swell, and it weighs me down,” she tells Inverse.

“I have blood circulation problems,” she says. “I was receiving treatment back in my country.” Norma lives with her nine-year-old daughter, who also made the trip from El Salvador. Her four-year-old son is still in their home country. “We didn’t have enough money for all of us to go, and I was worried something would happen to him on the route,” she says. “He was too young.”

Although asylum seekers like Cristina and Norma have a right to a bond hearing — which would remove the need for an ankle shackle — in many cases Geo Group contractors or ICE agents pressure the women to sign away their rights without a lawyer present. “What we hear from families is that even if they ask for counsel in those conversations [with Geo and ICE] they are denied counsel,” says Fischer. “They are told that if they don’t take the ankle shackle or want bond they’ll be detained for weeks more at a time, which is not true. There’s a very coercive practice to forcing families into accepting these ankle shackles.” Sometimes, bond is set too high for the asylees to meet, so they often feel they have no choice but the shackle.

The newly confirmed Attorney General Jeff Sessions, for his part, has very close ties to Geo Group. As noted recently by the ACLU, “GEO Group hired Senator Sessions’ former aides David Stewart and Ryan Robichaux to lobby in favor of outsourcing federal corrections to private companies. GEO Group is the same private prison company that was accused of illegally donating to Rebuilding America Now, a pro-Donald Trump super PAC, earlier this year.”

Paez, the Geo Group spokesperson, wouldn’t comment on the significance of the rise in Geo stock. “We look forward to working with both the new administration and the new congress in continuing our longstanding partnership with the federal government providing high-quality and cost-effective services while treating those entrusted in our care with the respect and dignity they deserve,” he says.

Contrary to those assurances, opponents of private prisons say there are structural explanations for why private prisons historically have worse human rights records than public facilities. Typically, private and public jails have to provide the same services and operate under the same general regulatory regime, says Alex Friedmann, managing director at Prison Legal News, which advocates against private prisons. “So the question is if they have to provide the same things and operate under the same policies, how do they make money? The answer is, the vast majority of the prison’s operational costs, whether public or private, have to do with staffing, payroll. How many people are employed, how much you pay, what benefits they receive,” says Friedmann. “In general, this is where companies make money. In general, they’re understaffed, they provide fewer or less costly benefits and less training.”

Don’t expect that to change anytime soon, says Friedmann. “The private prison industry in the immigration context has made itself essential. An estimated 70 percent of our immigrant detention beds are run by private contractors” he says. “Over-the-barrel is an overused phrase, and kind of trite, but it’s accurate to describe the situation.”

For her part, Cristina doesn’t have much hope that she’ll be able to stay in the United States but she’s terrified of being deported. She fled after her stepfather raped her, and fears that he’ll steal her child and continue to assault her if they’re forced to return to Guatemala. “I don’t know what to do,” she says. “I feel there’s no hope for me anymore.”