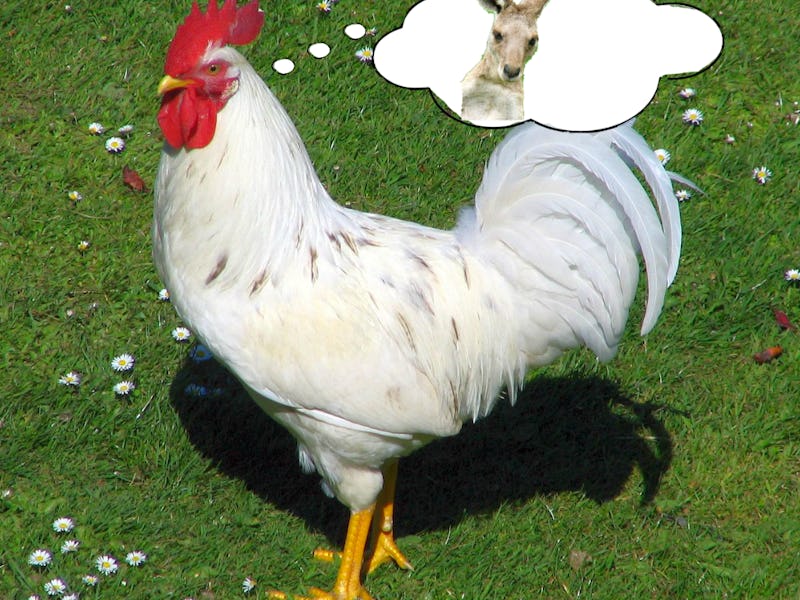

"Behavioral Synchrony" Explains Why Cluck Norris Thinks He's a Kangaroo

Go to Erldunda Roadhouse in Australia’s Northern Territory and you’ll find an unusual rooster by the name of Cluck Norris. Once a regular, homeless bird, Norris has developed some particularly wild habits ever since his adoption by the roadhouse’s managers. Norris now thinks he is the most Australian creature of all: the kangaroo.

According to Australian news outlet ABC, Norris hangs out with the kangaroos that live in at the roadhouse and “likes to bite like a kangaroo, and he likes to have a kick like a kangaroo as well.” This is certainly strange behavior, but one zoological theory explains it in schoolyard terms: Norris just wants to fit in so he doesn’t get beat up.

Animals who aggregate themselves into herds, schools, flocks, and colonies naturally synchronize their behavior with each other. This is called, appropriately, behavioral synchrony, and it’s thought to be a natural inclination that increases an individual’s chance of survival.

By trying to fit in, Norris is just attempting to save his ass; it’s thought that predators are more likely to attack an individual who can easily be singled out. Given his situation, Norris is doing well: Cain Powell, who works at Erldunda Roadhouse, told ABC that “He’s exactly the same, like the other ‘roos,” continuing, “They will come up and always want to get a pat off me, and he will want to come up and get a pat off me.” Powell says that he has seen roosters impersonate dogs and cats, but never kangaroos; still, the behavioral synchrony theory suggests that interspecies differences aren’t a dealbreaker.

Behavioral synchrony can manifest in a variety of ways, whether it’s a bunch of monkeys yawning at the same time or the mimicry of a newborn baby human copying the facial expressions of its mother. By acting like a kangaroo, Norris is adapting to his new flock; copying the behavior of the marsupials allows Norris to gain the locations of optimal feeding sites and lessen his chance of being singled out by a predator, a 2008 study in Cell suggests.

Sure, it’s tricky to imagine that a predator couldn’t visually pick Norris out of a kangaroo crowd, but Norris doesn’t know that. He — much like Leon, the turkey who thinks it’s a dog — inherently believes that it’s safer to blend in with his pseudo-flock.

Behavioral synchrony better explains what’s happening with Norris than any cuter narrative of an animal friendship. Those interactions are less easily explained — Mark Bekoff, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, told The Atlantic that “we don’t know” why animals, especially predator and prey, form cordial relationships. Don’t let him fool you: Norris is no friend to the kangaroos — he’s an opportunistic kangaroo-wannabe because he thinks it will help him survive Down Under.