What's the Difference Between a Replicant and a Host?

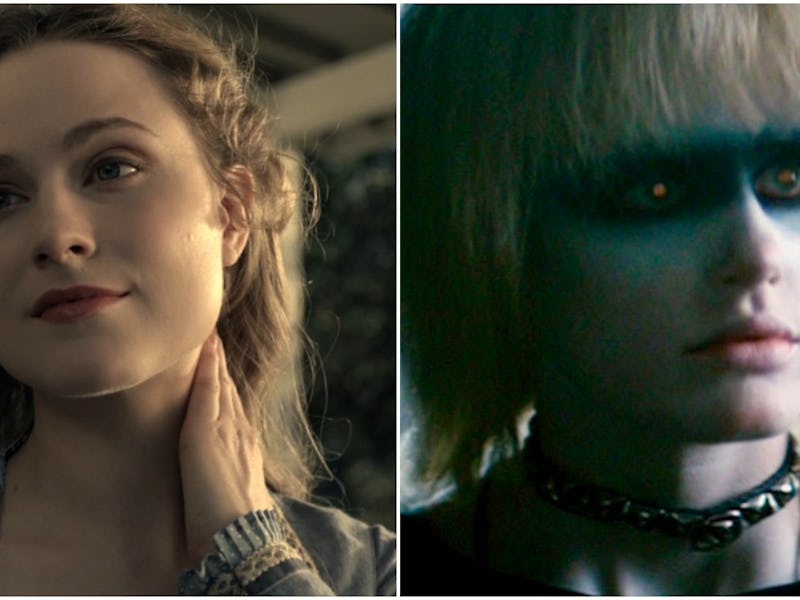

The artificial intelligence from 'Blade Runner' and 'Westworld' go head to head.

Not all robots are created equal. Case in point: The replicants from Blade Runner and the hosts from Westworld seem to be similar, but these subservient machines have a lot of differences. To pinpoint the differences between replicants and hosts, Inverse spoke to Selmer Bringsjord, the chair of the Department of Cognitive Science at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, who walked us through the important distinctions.

Narrative

The primary difference between replicants and hosts is predetermination.

Other than Rachael, Tyrell’s advanced replicant who in Blade Runner is said to have no set lifespan, the movie’s Nexus-6 models have a built-in contingency plan. Their four-year lifespan guarantees they cannot live forever. They’re supposed to do their menial off-world jobs and then expire. The Westworld hosts, on the other hand, have an ostensibly endless lifespan, as they are resurrected by the park’s technicians. They could, in theory, exist forever if they escape the confines of the park; they’re robots, so they don’t get sick.

The real split over narrative is whether the hosts and replicants stick to what they’re supposed to do. “The Westworld hosts are artificial creatures that are overtly narrative-based and narrative-entangled,” Bringsjord said. Robert Ford and park technicians program them to stick to specific loops and leave their interactions with humans and each other up to a false sense of chance. Everything is set in advance and completely under the control of their predetermined loops. Bringsjord posed it as a rhetorical question: “How do you manage to give a character autonomy and at the same time ensure the narrative arcs you want?”

Replicants are programmed without superficial differences from humans, and are given free consciousness to make their own decisions.

Self-awareness

This one’s a doozy, and will inevitably get mucked up even further as Westworld enters new seasons. As it stands right now, normal hosts are not self-aware, for obvious reasons (they probably wouldn’t like their lives if they knew the truth about them). And though hosts like Maeve and Dolores do have self-awareness, it might be predetermined, too. “They’re designed from a narrative point of view to convince you of that,” Bringsjord said, referring to the idea that the hosts’ sense freedom at the end of Season 1 was programmed into them by Ford. The same thing happens with Bernard, who finds out that he’s actually a host version of Arnold, which was all part of Ford’s plan in the first place. None of them are truly independent.

Things are more complicated in Ridley Scott’s classic film.

“Blade Runner is predicated on the assumption that artificial creatures are so sophisticated — cognitively and physiologically and biologically — that it even takes the highest echelon of human intelligence to figure out whether they are replicants,” Bringsjord said. Even though the movie posits empirical techniques like the Voight-Kampff Test to ascertain whether you’re dealing with a replicant or not, the robots like Roy Batty in Blade Runner have true emotion and self-awareness.

The two robot types come together when, like Bernard/Arnold, Rachael is programmed with memories from Tyrell’s niece and later wrestles with that revelation.

Then again, if Deckard himself is a replicant, as hinted at when Gaff gives him an origami version of the unicorn seen in his dream, the next versions of the Nexus robots do not have self-awareness.

Occupation

Here’s where replicants and hosts are more similar than different on a basic level, though there are still differences.

Replicants and hosts are created to do essential tasks, often for the benefit of humans. Leon and Roy Batty are militarized replicants, while Pris and Zhora are host-like basic “pleasure models.” The robots in Westworld are also assigned specific duties, many of which involves sexual encounters with park guests.

“The dynamic is very similar, but Blade Runner is harder-hitting,” Bringsjord explained. “It comes right at you and it ends up being a commentary on forms of slavery. Westworld poses that question for the eroticism of it. It poses more philosophical questions about what is intimacy, while Blade Runner only insinuates it.”

He also distinguished between how Westworld and Blade Runner deal with the implications of having robots doing menial jobs in our current reality. “How do we verify that autonomous machines with some range of power are in fact certifiably safe?” he asked. “Westworld is just absolutely spot-on relevant when talking about current robotic attractions for entertainment purposes. There’s definitely no elements of that in Blade Runner.”

God

Both Westworld and Blade Runner involve powerful corporations with vast technical capabilities creating robotic individuals, which symbolically carries a non-religious concept of God, or a maker. Specifically, the parallels between Tyrell and Ford as the gods of their respective stories are obvious. But whereas Blade Runner posits Tyrell as a monotheistic one true God, Ford has a lot of help.

“From very early on in Westworld you’ve got people monkeying around and hacking into these machines,” Bringsjord explained, inferring that many people are involved in the direct creation of each host, including Arnold. You don’t have that lack of purity in Blade Runner,” he said. While there are characters like Hannibal Chew who literally piece together replicants, it is Tyrell alone who creates their conception of themselves. Or as Bringsjord put it: It’s very clear that he’s working under the auspices and the intellectual direction of Tyrell.”