Experts agree that Mars was habitable at one point in history. The thing is, searching for habitable environments is a far cry from actually searching for signs of past or present life. To do that, a scientist at SETI explains, we need to get much more specific and look for actual habitats.

According to Nathalie Cabrol, a senior research scientist and director of the Carl Sagan Center, our current level of observation and astrobiological focus is only geared towards broad questions of potential habitability. That’s not good enough. In a marquee lecture at the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco on Wednesday, Cabrol explained how we need to take a more subtle, gradual view of the way the planet changed over time, rather than just categorizing them into three geological periods — the Noachian, Hesperian, and Amazonian periods.

“It’s a gross caricature of what happened,” Cabrol said. “You don’t understand how one went to the next.”

That’s important because early life would have been under “incredible environmental stress” as the Martian environment is historically less stable than Earth’s. Microbial life probably existed (if it ever did) in heated lakes created by impact craters and warmed by volcanic activity.

“The life will have to organize around oasis where they have resources,” she said.

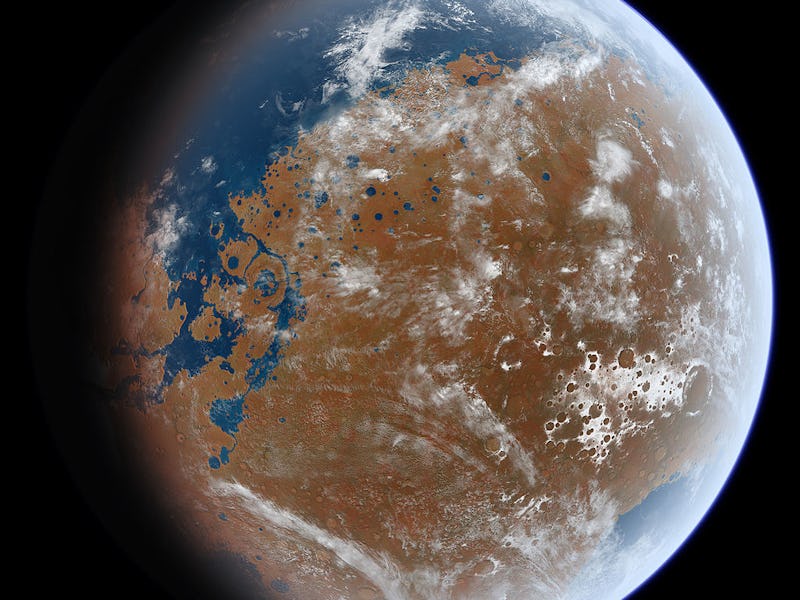

A water source regions on Mars.

Cabrol explained that looking at Earth can be helpful, so long as we don’t get too much of our terrestrial norms. “We’re seeking guidance, not truth,” she said. Different areas in and around the Andes mountains, including the Atacama desert and Altiplano, can be used as decent stand-ins for Mars over time, a technique Cabrol called “space for time substitution.” By observing how lakes deal with high levels of radiation, evaporation, and geological change, it colors how scientists need to look for Martian habitats on the micro level.

“We need to think about habitat fragmentation when we are looking for life on Mars,” she explained, noting that all these lakes likely divided into basins as they dried up over the ages. For the best chance of finding signs of life, scientists need to find “the last oasis that will last the longest.”

“We are just seeing tipping points, we are not seeing what happens on the subtle transitional level,” she said.

Cabrol continued, saying that we need to work on creating a “critical intermediate detection threshold” — a sort of middle stage between physical, surface level studies and the broad evaluations we’re doing now. She highlights mineralogy and composition data, as well as a greater understanding of climatic cycles and events that would actually affect the planet on a habitat level.

“We need to adopt the tool to the exploration, not the exploration to the tools,” she said, adding that explorers need to have specific places of interest identified years in advance before they land for a more thorough examination.

Otherwise, she declared, “we’re wasting time.”