For nearly 200 years, scientists have seriously pondered the possibility of life on Mars. It’s been a rollercoaster of dreaming: for a long time, the more we studied Mars, the more it looked the like the Red Planet was a cold, dry hellhole, lacking any of the essentials we consider a requirement for even the most primitive life.

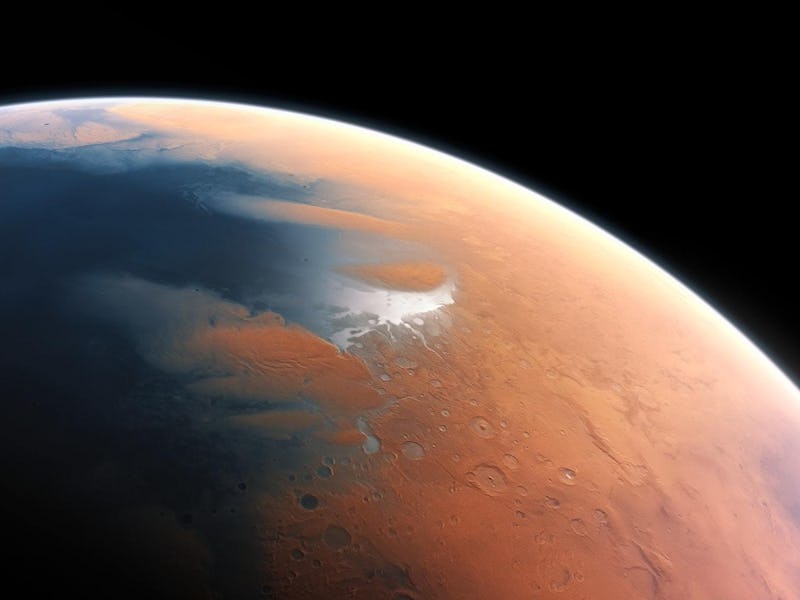

Then we learned Mars was once teeming in liquid water. With the discovery that liquid water currently exists on the surface of the planet, the prospects that aliens actually still call Mars home now seem better than ever. During a Tuesday workshop called “Searching for Life Across Space and Time”, NASA Goddard Space Center biogeochemist Jennifer Eigenbrode made a pretty strong case for why the newest data were collecting about Mars is dramatically raising the prospects we might find signs of past of present Martian life.

It all comes down to what we’re starting to learn about the presence of organics on the Red Planet. Eigenbrode remembers that during the Curiosity rover’s landing in 2011, most members of the NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory were “very doubtful we would ever detect organics on Mars.”

Nowadays, MSL’s scientists realize “organics are all over Mars.” And where there are organics, there’s the potential for those compounds to come together and lead to the genesis of living organisms.

Does that mean there’s life on Mars? Not necessarily. But organic molecules and compounds are the constituents that lead to life. Organics on Earth were by no means a guarantor that life would evolve, but it was certainly essential to the evolution of organic life.

During her presentation in Irvine, California, Eigenbrode pointed to analyses of Martian rock samples from the Gale Crater floor, Yellowknife Bay, and Parhump Hills — areas that are thought to have once possessed liquid water reserves — and they all had traces of organic macromolecules.

This is important, because 70 to 90 percent of organic matter is macromolecular. The complexity is critical to making life work, since metabolism is a complicated process that requires complicated pathways. Organic matter also fuels metabolism itself, since it’s one potential source of energy or carbon. “We need to be looking for this stuff,” said Eigenbrode.

But as Eigenbrode emphasized, the big question is what are the sources for these organics. They could be biological, but they might also very well be abiotic. They may have formed de novo — that is, on the planet itself — or be the result of deposits brought to Mars through meteorite crashes. “if this stuff is abiological,” she cautions, “…looking for organics is not looking for life.”

Nevertheless, “the presence of organic matter actually supports the habitability of an ancient lake,” said Eigenbrode. She’s specially referring to the Gale Crater, which is thought to have been home to vast body of water 3.6 billion years ago.

So what’s next? NASA’s Mars 2020 rover will be the key to understand the extent to which life may have or perhaps does exist on the Red Planet. The new rover will be fitted with an large suite of different instruments that can do a better job assessing the composition and concentrations of Martian organics and how they might relate to life on Mars. Just a little over four years to wait before two centuries’ worth of speculation can finally be confirmed or debunked.