Alien Life Might Live in Subsurface Ocean Worlds

If we found life on Mars, could it have been delivered from Earth? And could Earth’s water actually be from Mars? There’s the possibility of either scenario, explained researchers on Monday, during the first day of an alien-focused conference called “Searching For Life Across Space And Time: A Workshop,” at the Beckman Center of the National Academies in Irvine, California.

When we study water on other planets, we can analyze potential for life separate from the context of our own planet. In other words, we can look at the possibility there’s life with origins separate from our own. This allows us to better understand the biochemistry on its own terms, which might ultimately help us learn more about our own origins.

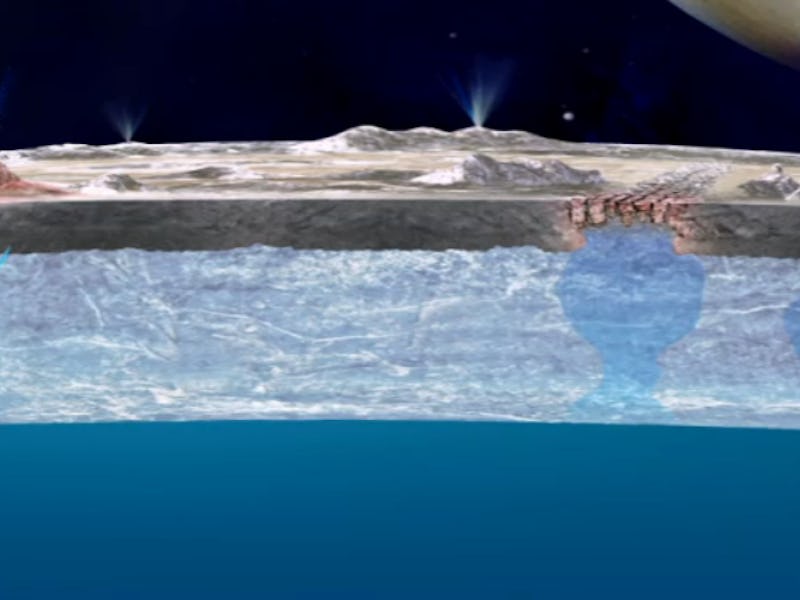

There are at least six moons (you could make a case for Pluto’s inclusion, too) that have or might have liquid water oceans beneath their icy exteriors — meaning, they might be able to sustain life. All the liquid water that might persist beneath the surface of these moons amounts to more than 30 times the total volume of water on Earth, which means a lot there are a lot of compelling places to search for life. Comparatively, the Earth with its relatively small amount of water, might have once been viewed — very long ago — as not a very promising place to search for life.

Arguably, Pluto should be up here also.

“When it comes to habitability,” said NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory astrobiologist Kevin Hand, “It really is not just about the liquid water. It’s also about the extent to which that water is interacting with rocks.”

We know of two standouts in that regard: Europa, which orbits Jupiter, and Enceladus, which orbits Saturn. We know Europa’s ocean has been there for a significant duration of its past, but we’re unclear on the history of water on Enceladus. Its global ocean could have potentially been maintained by tidal energy consistently through time, but the jury’s still out on that.

Life on Enceladus wouldn’t have the same “primordial soup” origins as life on Earth. Rather, it would by icy or hydrothermal. The more we learn about those pathways, the fuller a picture we can put together about how life arises across the solar system.

This is the actual caption by NASA, which can't be improved upon: "A masterpiece of deep time and wrenching gravity, the tortured surface of Saturn's moon Enceladus and its fascinating ongoing geologic activity tell the story of the ancient and present struggles of one tiny world."

We’ve already seen evidence of ocean “plumes” — water being sprayed into space — on Enceladus via the Cassini spacecraft. And Europa’s seafloor could actually be even more active than our own.

In an attempt to prove that Europa’s oceans were actively interacting with its seafloor, Hand and his colleagues looked to surface discoloration. The phenomenon itself is divisive: some believe it indicates salt, while others believe it’s a sign of sulfuric acid. The JPL team ran a recent experiment on what it calls “Europa in a can” — simulated conditions at their lab — that involved putting sodium chloride (a flat, white, spectrally uninteresting substance) into the chamber in the form of a brine that evaporated out water.

The puzzling, fascinating surface of Jupiter's icy moon Europa looms large in this newly-reprocessed color view, made from images taken by NASA's Galileo spacecraft in the late 1990s.

Post-irradiation, the salt had turned a dirty, yellow-brown color — a sight recognizable from imagery of Europa’s surface. They think it means that on Europa, the discolored regions are geologically active, the result of irradiated salt coming up from the ocean below — and thus an active, dynamic body of water, the kind of place we might one day find life.