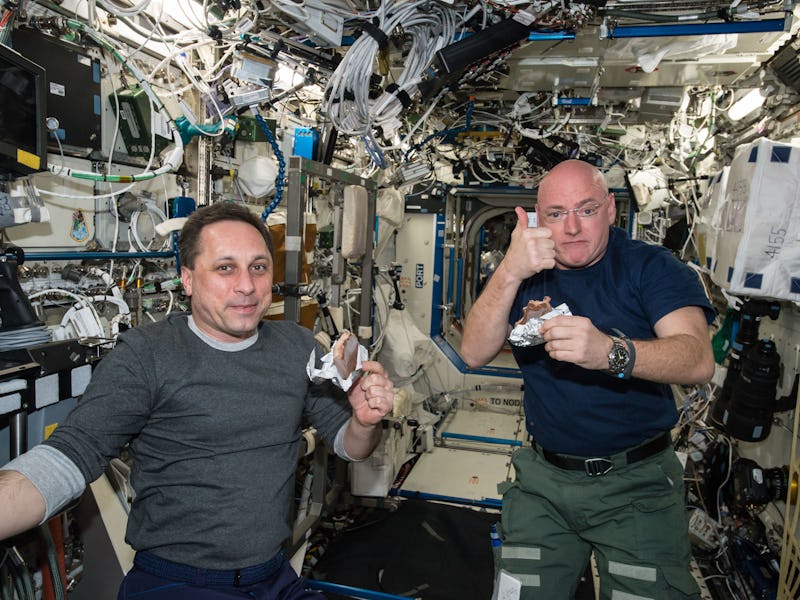

Scott Kelly was the first astronaut to spend a year in space, but he will be far from the last. Eight months after he and Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko came back to Earth after 342 days aboard the International Space Station, NASA is expressing hopes to conduct at least five more year-long missions, and collect much more data relevant to the effects of long-term duration in space on human health.

Simply put, Kelly and Kornienko by themselves do not provide enough data for NASA to make rigorous assessments on how microgravity and a space environment affects astronaut physiology. To extrapolate we need to have more time in space, and more observations,” William Paloski, the director of the Human Research Program at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, told Ars Technica.

And it’s not as if NASA is only just beginning to prep for follow-up studies. “We started working on additional missions two years ago,” Paloski said.

Five more missions is probably all NASA can so far plan for. The ISS is expected to stay operational only up to 2028. The earliest NASA could start these missions would be September 2018. That gives the agency just about 10 years to pull together astronauts to agree to one-year stays in low Earth orbit, although the agency would shoot to wrap up by 2024, with the potential for some of those missions to overlap with one-another.

According to Paloski, NASA would ideally structure the missions like the Kelly-Kornienko flight: one Russian and one U.S. or international partner paired to stay for an entire year supported by a rotating crew with shorter stints. Future one-year missions would include women and younger astronauts to get a broad collection of participant data.

It’s unclear whether all of this could conceivably move forward. Russia is winding down its commitment to the ISS and is expected to downsize the number of cosmonauts it keeps on the station from three to two.

Paradoxically, according to Paloski, Russia seems to also prefer conducting more audacious long-duration missions, such as simulating a Mars mission by having a crew stay at the station for six months, landing on Earth and residing in isolation for three to six months, and then traveling back the ISS for six months — to mimic the commute and stay at the Red Planet.

In an effort to keep things simple and keep the science streamlined, NASA wants to just stick with one-year missions.

Kelly’s year in space thrusted him into the spotlight as the new face of human exploration at NASA. He is still participating in the analysis of all of the physiological data relevant to the effects of a lengthy stay in space — and so is his twin brother Mark, who is acting as a control subject for the study.

Kelly was recently selected as the United Nation’s newest ‘Champion of Space’ — which essentially makes him the world’s official space cheerleader. Not a bad way to kick off a life of retirement from NASA.