Why Are We Stuck with the QWERTY Keyboard?

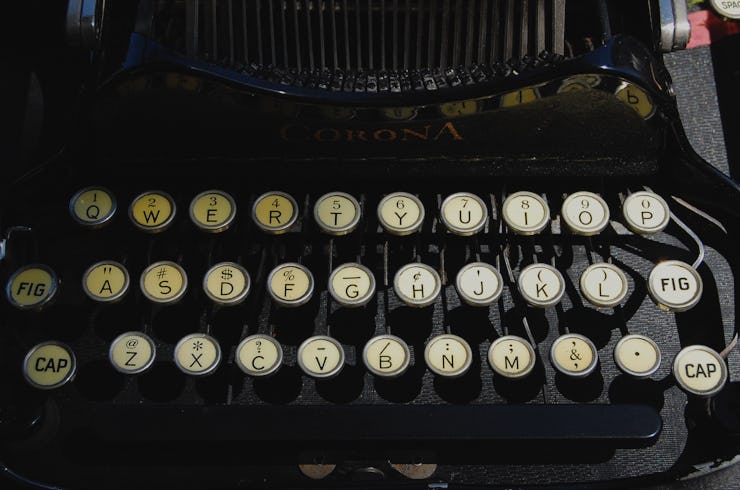

Slow down, dear typist, or else the paper will jam.

Excerpted from New Scientist: The Origin of (almost) Everything, written by Graham Lawton and illustrated by Jennifer Daniel.

Technology often contributes new words to the English language: television, hoover and iPod to name a few. But none have origins quite like the word QWERTY.

As one of the world’s most ubiquitous technologies, used by billions of people every day, we rarely give a second thought to computer keyboards. But behind the ordinariness and familiarity there’s something very odd about them. Why are the letters arranged that way?

The world’s love-hate relationship with the QWERTY keyboard began in a small workshop in Milwaukee in 1866. That was where a publisher called Christopher Latham Sholes began work on an invention he hoped would make him rich: a machine to automatically number the pages of books.

Sholes was joined by an inventor friend called Carlos Glidden. In July 1867, he happened to read a short description of a “type-writing machine” in Scientific American. It appears to have inspired them to change course and create ‘a machine by which … a man may print his thoughts twice as fast as he can write them’.

Piano or typewriter?

A year later they were in possession of three patents. You’d be hard pressed to recognize their creation as a typewriter, though. It looked more like a piano, with ivory and ebony keys, one for each letter.

The machine was prone to jamming and the lines of type tended to drift off course, but Sholes used it to write to potential investors. One of them, James Densmore, immediately bought a quarter share of the patents, sight unseen. But when he got to Milwaukee to cast an eye over his investment, he was less than impressed, declaring it to be ‘useless’. Nonetheless, Densmore believed in the general idea and urged Sholes to continue.

What happened next is a little murky. Sholes filed another patent in 1872 which shows the piano keyboard had been dropped in favour of rows of circular keys, but it did not specify which letter waswhere.

Then, almost out of the blue, QWERTY (almost) appeared. In August 1872 Scientific American published a glowing article about the ‘Sholes’ Type Writer’, illustrated with an engraving of the machine showing a four-row keyboard with a second row starting QWE.TY.

QWERTY comes together

Densmore demonstrated the typewriter to engineers at E. Remington & Sons, a gunmaker based in New York that had branched out into home appliances. Remington signed a contract to manufacture the machine, and produced a prototype with another slightly different keyboard: QWERTUIOPY

Sholes was apparently unhappy and demanded that the Y be reinstated between the T and the U. Remington agreed, and for the first time QWERTY came together. Remington put its No. 1 Type Writer on to the market in 1874 and it quickly became the world’s first commercially successful writing machine.

By 1890 there were more than 100,000 QWERTY keyboards in use in the U.S. QWERTY, then, clearly evolved gradually from an initial design in the 1870s. But where did the arrangement come from?

One often-repeated explanation is that it was designed to “slow the typist down” in order to stop the mechanism from jamming, a bug that dogged earlier designs. This was supposedly achieved by keeping common letter pairs apart.

But that cannot be true. E and R, the second most common letter pair in English, are next to one another. T and H, the most common of all, are near neighbors. A statistical analysis in 1949 found that a QWERTY keyboard actually has more close pairs than a keyboard arranged at random.

Another urban myth is that it enabled salesmen to impress customers by rapidly typing ‘TYPE WRITER QUOTE’ from the top row. It’s a nice idea – and it does seem unlikely that these letters would appear together by chance – but there is no historical evidence for it.

Perhaps a more convincing though prosaic reason is that the keyboard is simply a semi-random rearrangement of the original piano-style keyboard.

We’ll probably never know. A century after Sholes finalized the keyboard, historian Jan Noyes of Loughborough University published a lengthy analysis concluding: “There appears … to be no obvious reason for the placement of letters in the QWERTY layout.”

Worst possible design

One thing is clear: the keyboard was not designed with touch-typists in mind. As Noyes pointed out: “the original QWERTY keyboard was intended for ‘hunt and peck’ operation and not touch-typing.” Touch-typing was a later invention.

That may explain the well-known practical shortcomings of QWERTY. In the 1930s, as typewriters and typing became more common, researchers began questioning its usefulness. One fierce critic, educational psychologist August Dvorak (a distant cousin of the composer), had a team of engineers test 250 keyboard variations and concluded that the QWERTY design was one of the worst possible arrangements.

He had ulterior motives. In 1936, Dvorak had patented an alternative, the Dvorak Simplified Keyboard. He claimed it was easier to master, faster to use and put less strain on the hands. But it did not take off. In fact, since becoming the de facto standard, the QWERTY keyboard has seen off dozens if not hundreds of supposedly superior competitors. It transferred seamlessly from mechanical typewriters to computers and now on to touch screens, and is ubiquitous wherever the Latin alphabet is standard.

Yet despite its dismal reputation, it is not all that bad: a study in 1975 found that an accomplished typist could attain over 90 percent of the theoretical maximum speed.

The real reason for its stubborn persistence is inertia: imagine the cost of designing, testing and manufacturing an alternative and then retraining billions of people to use it. As long as keying letters into a machine is needed, QWERTY is here to stay.

The illustration below appears best on a desktop computer.

Excerpted from New Scientist: The Origin of (almost) Everything, written by Graham Lawton and illustrated by Jennifer Daniel. Available now from Nicholas Brealey Publishing.