The impending threat to birth control access posed by the incoming Trump presidency has women scrambling to have a fallopian tube-shaped piece of metal wedged between their fallopian tubes. The reason? IUDs are contraceptive implements that are uncommonly good at preventing unwanted pregnancies — and might not be covered by the Affordable Care Act for much longer than the average American presidential term.

In the United States, intrauterine devices, as they’re medically known, come in two flavors: either pure, nonhormonal copper or progestin-releasing plastic. Both have sperm-slowing effects but use slightly different strategies for doing so.

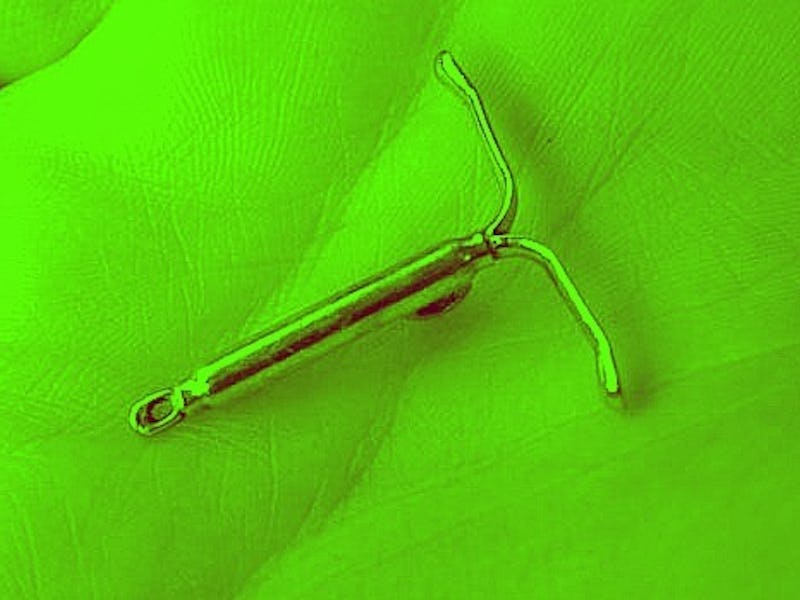

The copper types, known in America by their trade name Paragard, are also known as “coils” because they consist of a thin tube of plastic wrapped in a spiral of metal. Like elbows resting against a ledge, the T-shaped arms of the IUD rest at the top of the uterus, where its coil dangles and releases copper ions below. The bronze-colored metal is a naturally occurring spermicide and induces the uterus and neighboring fallopian tubes to secrete fluids containing copper ions together with sperm-slowing prostaglandins and white blood cells. This mucus flows down into the cervix to create a sperm-hostile zone. Pregnancy, in 99 percent of cases, doesn’t stand a chance for the next 12 years — unless the IUD is removed earlier.

Copper IUDs are also known as "coils" because of the spring-shaped loops of metal they contain.

Hormonal IUDs — known by the trade name Mirena in the U.S. — work in a similar way, except synthetic progesterone plays the sperm-killing role instead of copper. The small tube of plastic rests at the top of the uterus, just like the coil, where it releases hormones that make the mucus in the cervix too thick and sticky for sperm to glide through. It also keeps the uterus lining from becoming too thick, which, if some intrepid sperm does manage to fertilize an egg, prevents implantation on the uterus wall — a necessary step for pregnancy — from taking place.

The hormonal IUD uses progesterone to do its spermicidal bidding.

Insertion requires the help of a gynecologist and can be painful, but once it’s in place, women can generally forget about them. The copper types are effective for up to 12 years, while the hormonal versions last between three and six years. They don’t come cheap: According to a study published in Contraception Journal in 2015, the Affordable Care Act made it possible for 90 percent of insured women to get an IUD for free, but if funding is taken away, their costs can range from $55 to $2,600, depending on the clinic, according to an analysis by Clear Health Costs.

The devices aren’t perfect: They have side effects that include heavier menstrual bleeding, more painful cramps, and they can cause irregular periods. Still, the mad post-election scramble to women’s clinics shows that the benefits strongly outweigh the costs. Not only are they the most effective form of birth control out there, but they’re ultimately cheaper and more convenient than the once-daily Pill or the clumsy condom — which might be the only options left come January.