Paul Has Been Dead for 50 Years

Fifty years later, the mystery of Paul's fake death still haunts us.

On November 9, 1966, Paul McCartney was prematurely killed, the victim of a bizarre conspiracy theory. In many ways, the hoax was also the original crazy fan theory. Fifty years later, we know Paul is definitely alive — and still making music! — but in all the strange lore and mythology surrounding the Beatles, this theory is probably the most confounding. Here’s a brief guide to understanding why Paul was thought to be dead, why we know he isn’t, and why people still care.

The basics are as follows: Some fans thought that the Beatles actively put clues in their albums designed to fuel a conspiracy theory that McCartney had died in 1966 and was replaced by lookalike actor named William Campbell. While the conspiracy theory puts Paul’s death in 1966, the theory first surfaced on October 12, 1969, one month after the official (and legally-binding) break-up of the band. Patient zero of the “Paul Is Dead” Theory was an American DJ named Russ Gibb of radio station WKNR-FM. Gibb claimed he got an anonymous phone call saying that Paul McCartney was dead, and actually had been dead for just under three years.

In a series of very lengthy 1970 interviews for Rolling Stone — later republished as the 1971 book Lennon Remembers — journalist Jann Wenner asked John Lennon what he thought about the whole conspiracy theory, and John Lennon was unequivocal: “That’s bullshit. I don’t know where that started. It’s balmy … the whole thing was made up. We wouldn’t do anything like that.”

Maybe the fans didn’t know the band as well as they thought they did, because they had plenty of “evidence.” The first piece was the suggestion that the end of the song “Strawberry Fields Forever” features John Lennon chanting “I buried Paul.” The comprehensive Beatles biography — The Love You Make, written by former Apple Corp. manager Peter Brown and Steven Gaines — puts it like this: “As much as it might have been John’s sentiments at the time, it was hardly true.”

And yet, the search for retroactive pieces of evidence backing the theory didn’t stop. When fully formed, the theory looked like this: Paul was killed in a car crash on November 9, 1966. This car crash is referenced in “A Day in the Life” and more vaguely in “I Am the Walrus.” After this point, Beatles replaced Paul with Campbell, who had won a Paul McCartney lookalike contest. This “explains” why the Beatles introduce “Billy Shears” in the first on track of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. And if you play the song “Revolution No. 9” from The White Album backwards someone says “Turn Me on Dead Man.”

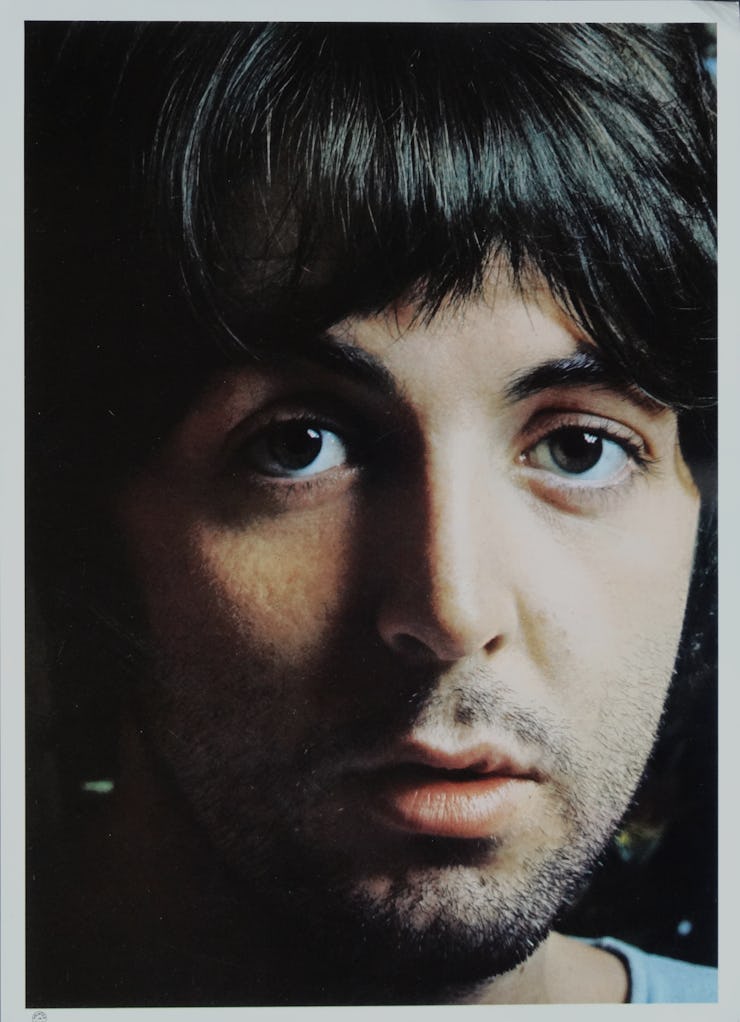

Most famously, the cover of Abbey Road presents a funeral procession: John as a priest, Ringo as a pallbearer, George as a gravedigger, and Paul, of course, as a corpse. Various photographs were analyzed and retroactively filled with more bits of evidence: A White Album photograph gives us a scar on Paul’s lip that he wasn’t supposed to have, and the Sgt. Pepper’s photos have him looking more ghost-like than the other Beatles.

As Brown and Gaines explain in The Love You Make: “It seemed as if a Paul-is-dead mini-industry developed overnight. One of the more ghoulish entrepreneurs published a magazine devoted to the subject.” In 1969, these kinds of fanzines certainly helped to propagate the notion that Paul was dead, something which seems pretty impossible (at least long-term) with the way information travels on Facebook. Brown specifically asked Paul to tell the press that he was alive, but Paul declined, wanting to simply let it go and hang out in his farm in Scotland. “I finally called Paul on his private line at the farm and told him that work at Apple was being disrupted by thousands of queries about his health,” Brown writes.

It was in an interview with Life Magazine in which Paul McCartney cleared up once and for all the idea that he was indeed and in fact alive. “The rumors of my death have been greatly exaggerated,” he said. “However, if I was dead, I’m sure I’d be the last to know …”

Call it a “hoax” or a “fan theory” — the notion that Paul was dead was obviously false — but it was pervasive for one specific reason: At least one of the clues did seem straight-up weird. In the White Album song “Glass Onion,” John Lennon sings: “Here’s another clue for you all. The Walrus was Paul.” Now, despite containing a great “oh yeah” (which was sampled by Danger Mouse for the mashup album “The Grey Album) no one would claim “Glass Onion” as their favorite Beatles song, mostly because it’s so self-referential and, basically, silly.

And yet, why does John say, “Here’s another clue” if he wasn’t at the very least trying to stir up some kind of trouble? Obviously, Paul wasn’t (and still isn’t) dead, but Lennon denying that he or any of the the other Beatles didn’t know or understand where this came from in the first place is the part that still seems strange. Obviously, claiming that Paul was really alive make sense. But denying any involvement in the prank to begin with? Seems fishy.

So, on this day, celebrate the fact that Paul McCartney is in fact alive. But, consider this: Everyone knows John Lennon was a witty and surreal humorist. Would he have had the foresight to plant a few “Paul Is Dead” clues on a few albums, and then, a few years later phone a radio DJ with the news? John was in a pretty earnest phase at that point, but, he did hate Paul McCartney in 1969. He even referenced the theory in his anti-Paul song “How Do You Sleep” when he sang, “Those freaks were right when they said you were dead.”

Still, even if Lennon didn’t call the radio station (which really, he probably didn’t), and we accept it to be true that Gibb did receive a phone call, who made that phone call and why? In the annuls of weird pop culture mysteries, that question, the identity of the person who started the rumor, is bizarrely, still haunting.