Why You Feel the Urge to Blame Someone for Tuesday Night

You're primed to blame someone after you've been wronged.

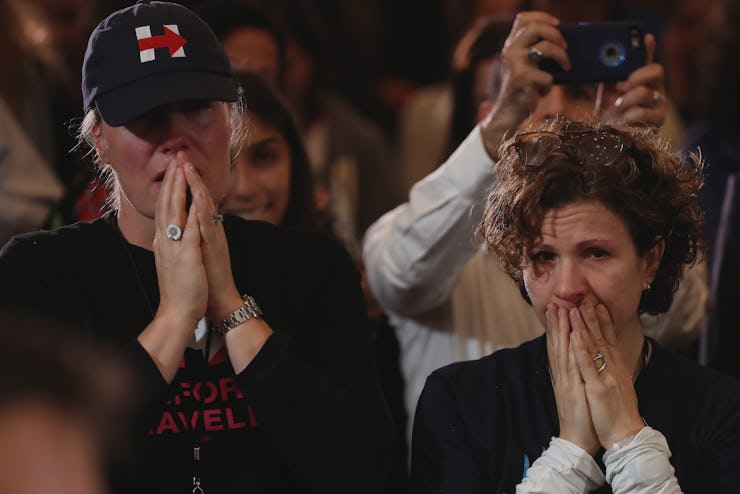

The primary question in the post-mortem of the presidential election is who to blame for Clinton’s performance at the polls: Is it the fault of third party voters? Is it the white and wealthy that Democrats can blame, or the white who identify as the “forgotten men and women” Trump acknowledged in his Tuesday night victory speech?

The list is inconclusive. Yet in the immediate aftermath of a situation where humans feel wronged, the emotional benefit of blaming lies not in a collective choice of villain, but in the act of blaming itself. Democrats should understand all too well that long-term and deep-seated blaming can lead to dangerous irrationality. But a person’s instinct to blame shouldn’t be faulted — in fact, as an initial response, blame may help that person’s ability to heal.

“If you look at blame as a combination social-emotional event, yes, it can be helpful for someone,” Brian Quigley, a social psychologist and senior research scientist at the University at Buffalo, told Inverse. “It plays a social function because it helps us identify to others that something is wrong.”

Scientists believe blame is a primal impulse developed by humans over millennia as an adaptive strategy for pain. How much blame we decide to place on someone stirs from the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain that controls punishment decisions. Humans blame others to maintain social order and to alert others that they have been wronged. While the choice of who and what to blame is an individualistic one based on values and beliefs, the actual act of blaming is a universal reaction.

According to a model designed by psychologist K.G. Shaver in 1985, blame comes in sequential stages: casual attribution, responsibility attribution, and then the actual blame. The “penultimate stage of blame,” Shaver argues, is when a person blames someone else for knowingly and voluntarily committing a social or moral transgression. Blaming is intuitive and automatic, an impulse to express and defend values and expectations.

“We are more likely to blame someone that we believe has intended to do us harm,” says Quigley. “But there is another aspect besides the issue of intent. Sometimes blame results from the idea that the person should have known better. I think that is probably what you’re seeing in a lot of election results today. The idea of, ‘Help me out, how could you vote for this person?’”

But how long blame is beneficial for someone is unquantifiable. A person’s mind evaluates another’s behavior, then decides there must be consequence, which in turn affects their own behavior.

Blaming a wrongdoer enforces personal and social boundaries, but it doesn’t come without any cost at all. “Blame and anger have a reciprocal relationship — the more you blame someone, the angrier you become, and the angrier you are, the more you are likely to blame,” says Quigley. “You may still blame someone after you have decided to forgive them.”

Blame is the rational response that is seemingly irrational — but is completely natural. It can also hold you hostage too long: Neurologists understand that it’s important to express anger and blame effectively and allow ourselves to feel those emotions. What they don’t know is how to find the grace to eventually let that blame go.