The Beginning and End of Retrofuturism

What do we make of a white evangelical future now?

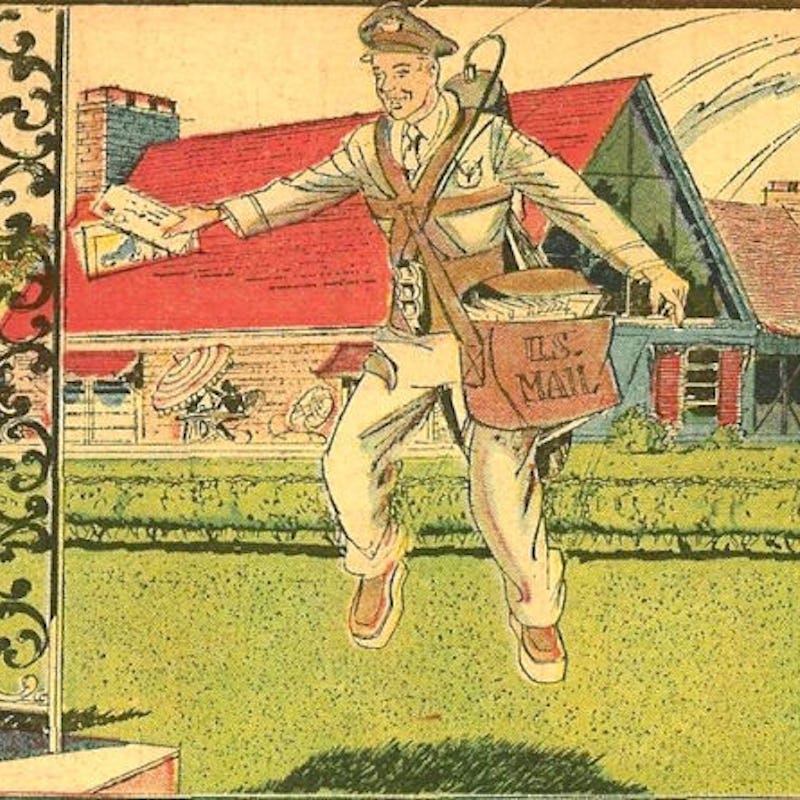

The pomaded, uniformed, and gleeful mail man jet packing into the yard of a happy homemaker with a fist full of paper correspondence looks, depending on where and when you’re sitting, absurd. The image suggests a techno-determinist view of the future that sidesteps the idea of social change or turbulence with the reckless abandon and agility of a seasoned copywriter. And that’s the appeal of retrofuturism: the juxtaposition of cultural and demographic stasis with temporal and technological shift. The pages torn from Popular Mechanics in the fifties make their modern fans smile because they depict an intellectually ambitious task of predicting what will come next, being pursued in the most intellectually lazy way possible.

Retrofuturist imagery was at its most searched during the George W. Bush presidency, but there has been a rebound in Google queries of late after a major dip in the early 2010s. This imagery is now consumed with real pleasure and real irony. After all, the popularly accepted narrative is that America changed for good in the late sixties. These illustrations were outdated almost immediately.

But if hubris looks like a mail man in a jet pack, foresight could look like a hurriedly drawn suburban idyll.

Several weeks ago, the Public Religion Research Institute released the results of the 2016 American Values Survey, a standardized culture test filled out by 2,010 Americans representing national demographics. The subjects of the survey were divided on a number of issues, but none so severely as the vector of history. Some 51 percent of respondents believed life in America had changed for the worse since the 1950s; 48 percent believed the opposite. Those reactions broke down along racial and religious lines: Nearly three quarters of white evangelical Protestants claimed that life in America has gotten worse.

A game of poker, played at speed.

This response can only be understood when broken down into its constituent parts. The first claim being made is that America has changed. The second is that the change has been negative.

The acknowledgement that America has changed is important because many commentators and pundits have and will maintain that the social bloc that buoyed President-Elect Donald Trump to Victory is attempting to bend the timeline of progress back on itself. This is not the case. White evangelicals are not ignorant of technological or cultural shifts. They aren’t ignoring the process, just contesting the significance of the results.

Given that the purchasing power of blue-collar workers has largely gone up — pay hasn’t kept up with inflation, but the cost of consumer goods has fallen — the claim that life in America has gotten worse is clearly not a consumerist one. This means that life has gotten worse for white evangelicals in immaterial ways. It’s totally fair to point to skyrocketing education costs, unstable housing markets, and a widening income gap, but its also clear that the internal lives of a specific class of Americans have been diminished. America may or may not be in decline, but thinking has made it so even if history has not.

The present is two-dimensional — too narrow for much consideration. By temporal default humans spend a tremendous amount of time thinking about the future. Research shows that these thoughts can be siloed into two categories: expectations and fantasies. These manners of thinking work differently in that positive expectations, informed by reality, lead to hard work and successful performance. Positive fantasies, on the other hand, lead to lower effort and diminished performance. Polling numbers show that white evangelicals have had low expectations and Trump’s rhetoric — “Your dreams will come true” — is indicative of an openness to positive fantasies. Which brings us back to the imagined future, the one with the happy homemaker and the jetpack.

The black kids were sick that day.

The picture is perhaps more plausible than it previously appeared. But what does it depict now? Perhaps retrofuturism isn’t about the humor of cultural stasis juxtaposed against technological progress. Perhaps it’s about cultural reversion on the other side of technological and social progress. These images — all these smiling, pomaded men and their indistinguishable wives — depict both the toys and the values that white, caucasian, and mostly male illustrators thought Americans would have. These values are uniformly capitalistic, consumerist, heteronormative, and bourgeois. The growth of the middle class at that period in history gave would-be futurists the sense that prosperity would create a puddle in the economic middle, a vernal pool out of which generations of nearly identical nuclear families could squirm.

The internet has spent half of its existence chuckling at these dull-nubbed Nostradami, but perhaps their failure to understand how external forces could affect culture was a product of an understanding that culture trumps technology. Maybe they understood that culture trumps everything.

The view from Russia.

The illustrators who gave us the futuristic images we repurposed as retrofuturism didn’t draw many Black people, Latinx people, Asian people, gay people, trans people, or prisoners. They had the confidence to believe that they would inherit America and that the others would exist on the other side of the pleasure dome walls. They had positive expectations with the same conviction their descendants now have negative fantasies.

In the wake of a tectonic political event, images of a whitewashed future can no longer be seen as illustrations of an abandoned fantasia. It was never abandoned. And it wasn’t retro after all.