What Watching Your Favorite TV Character’s Death Does to Your Brain

Beloved characters die on TV all the time. Are you really grieving them or just watching along?

Shortly before bashing Glenn’s head to a bloody pulp, The Walking Dead’s new big villain, Negan, tells his assembled prisoners that they are powerless to stop the carnage he’s about to unleash. “You can breathe. You can blink. You can cry,” he oozes. “Hell, you’re all gonna be doing that.”

He might as well have been talking directly to Dead’s massive audience. Glenn was a beloved character who had been a part of fans’ lives since the second episode of the show’s first season. They’d gotten to know him over the course of six years, and when he died, they were shocked, powerless to do anything but mourn this delivery boy turned heroic zombie slayer.

“I haven’t been this rattled since I was a kid,” Redditor DreadnaughtHamster posted on The Walking Dead subreddit, which was filled with shocked reactions and tributes following the episode. “[Glenn was] the character I connected with the most, so it was like losing a friend,” he told Inverse. Countless fans joined him in grieving Glenn across other platforms.

But, is this feeling of sadness about the loss of a fictional character actually grief?

Fictional characters meet tragic ends on a weekly basis, and while viewers are certainly sad, it seems inherently odd to compare it to “real” grief. Dr. Robin Hornstein, a psychologist who spoke to Inverse, recalled how a friend once told her that she was “‘really sorry that you lost your make-believe friend that you’ve never met who doesn’t exist,’” following a death on Orange Is the New Black. “I was like, ‘screw you!’” Hornstein recalled. The point this licensed psychologist was making: anyone who has lost a favorite fictional character knows that the pain feels real.

It might not seem like it, given the weekly bloodbaths on shows like The Walking Dead and Game of Thrones, but major characters dying on TV is a relatively new trend. Shows weren’t serialized during the first several decades of TV history, and they didn’t have massive ensemble casts like today’s epics, so the few characters on each show were safe.

“You knew whenever you sat down to watch an episode of Starsky & Hutch that neither Starsky nor Hutch was going to end up dead at the end of the episode,” Robert Thompson, a media scholar and professor at Syracuse University’s Newhouse School, joked to Inverse. That didn’t really start to change until the 1980s, when shows like St. Elsewhere began to kill off major characters. Though, even then, such deaths were a relative rarity.

In TV’s early years, the death of a someone important truly shocked viewers. The unexpected passings of Edith Bunker on the All in the Family spin-off Archie’s Place and Lieutenant Colonel Henry Blake on MASH were landmark moments. “Back then, it was possible not to see it coming,” Thompson says.

Even though the body count on TV started to tick up after the ‘80s, it’s really only been during past few years — credit the rise of social media — that we’ve entered the era of public mourning for fictional deaths.

Message board posts, fan art, fan fiction, tribute, tweets, and reaction videos — and even some IRL shrines — serve as memorials, “reflecting on the relationship that the fan had with that character or the value and meaning the character created for them,” explains Susan Kresnicka, a cultural anthropologist engaged in a year-long study on fandom for the brand consultancy Troika.

Sure, ultimately it’s fan engagement, but a lot of the mourning demonstrates “energy and emotion that goes far beyond what you’d expect if it were just fun,” she explains.

Fans mourn because these characters had become a part of their lives. They’re entering homes on a weekly basis (or more often) for years. When they’re taken away by a cruel plot twist, viewers feel a certain sort of emptiness.

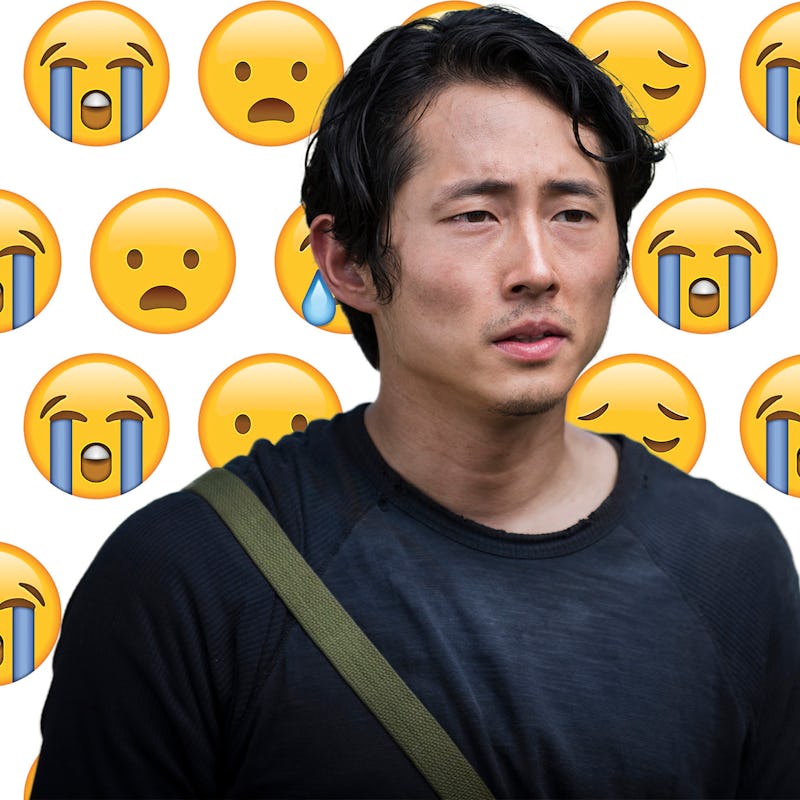

Glenn's killer, Negan.

Fans don’t just grieve for characters. In some cases, the end or cancellation of a long-running show can hit even harder. Thompson says in some ways the death of Dumbledore paled in comparison to the ending of the Harry Potter series, which had been a fixture of many young readers’ lives for as long as they could remember. “That universe was — I’m not going to say as important as the real universe they lived in, but it was certainly an important part of their real universe,” he says.

But unlike death in our real universe, characters are resurrected and series are rebooted, bringing the entire cast back to life — see, for example, Cursed Child and the upcoming Fantastic Beasts spin-off franchise. “The writers can change the script at any time,” trauma grief counselor Veronica Sites explains to Inverse. “Not so in life.”

When Is It Time To Seek Professional Help?

“Grief is life-altering,” Sites says. When a fictional character dies, viewers might naturally feel sad, angry, and frustrated. The mourning process shouldn’t wreak any deeper havoc on their lives. “If it goes beyond that, it may be time to see a professional to distinguish what is healthy and what may have crossed a line of reality,” she explains.

So, yes, of course losing a beloved character isn’t the same as losing a real loved one. The hurt isn’t as deep, nor does it last as long. By the Wednesday after The Walking Dead, DreadnaughtHamster, the Redditor who was “rattled” by Glenn’s death, was doing fine. “I don’t feel nearly as strongly as I did, probably because it is fiction and not real life,” he writes. But it wasn’t a totally empty feeling: “It has made me contemplate and ruminate on a lot.”

“I see the whole thing as being about the closeness of the relationship. If someone who is very very close to you in real life died, obviously the loss is cosmically that much greater,” Kresnicka says. A close family member’s death tends to hit harder than that of a friend of a friend. The relationship fans have with fictional characters is indeed a close relationship, but it’s inherently less immediate than with a real loved one — and the grieving process reflects that. — even in the degree to which viewers feel pain at a character’s death. For example, in The Walking Dead, Glenn wasn’t the only character that died — Abraham took a bat to the head first. But most viewers felt a deeper connection with Glenn since they knew him longer and more intimately, so the grief was more powerful, mirroring, but not replicating, real-life relationships.

“We talk about fandom as being love with a little distance. I think it’s grief we feel in fandom too,” Kresnicka says. “It’s like grief with just enough distance that it doesn’t have that incredibly profound sting on the inside of our lives. But the grief on the outside can look very similar.”