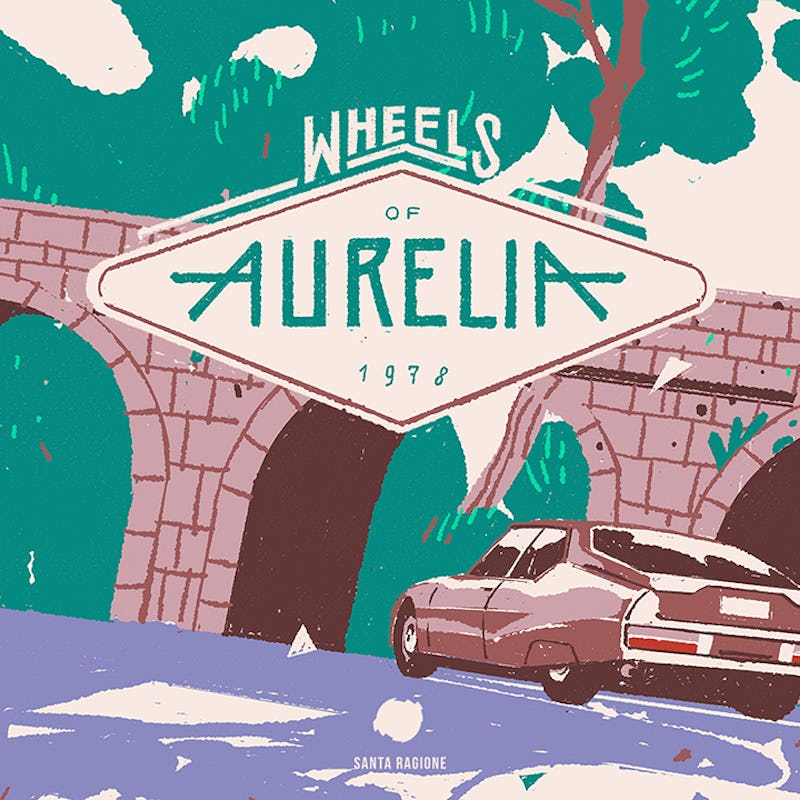

'Wheels of Aurelia' Is a 1970s Road Trip About Talking

When is a driving game not really a driving game? When it's 'Wheels of Aurelia.'

In most racing games, the ethos is pretty clear: Drive fast, pass the checkered flag first, and bask in the glory. In Santa Ragione’s recently released driving game Wheels of Aurelia, it’s a little more complicated than that. Sure, you can race in it, but you don’t have to; Heck, you don’t even have to drive, as the game will follow the road for you, albeit at a snail’s pace. No, what Wheels is really about is road-tripping, the sense of going nowhere specific at no particular speed, and the conversations that can result from that.

To get a better sense of how this self-proclaimed “narrative driving game” approaches this unique mission, Inverse met up with the designer, producer, and programmer of Wheels, Pietro Righi Riva, at this year’s IndieCade in Los Angeles.

Yu Suzuki, the much-acclaimed developer of Shenmue and many other titles, once noted that his Outrun series was all driving games, not racing games. How would you say that dichotomy applies to Wheels?

Wheels is the natural evolution of that thought in that it abandons the typical format of a racing game in the competitiveness that is still present in Outrun. It’s all about the setting and the story, which are background elements in Outrun — what a Japanese developer thinks about fictional America — whereas in Wheels, it’s real Italy. Although, we did take some techniques from Outrun and that generation of games. For example, the road in Wheels of Aurelia isn’t the road in real life, and it looks like more like an arcade racer.

Games often struggle to come up with unique settings, but Wheels’s post-fascist Italy certainly gives it a striking atmosphere. As a developer, how did you work with this to give it a unique sense of place?

This “post-fascist” quality is something that’s debated in the context of Wheels. The game argues that it’s still fascist, and you could say the same about today. The idea about making a game in the ‘70s was ultimately to make a game about Italy today. We were looking at the generation in which our parents grew up, and we really want to understand the political climate at the time and make it emerge through the characters that populate the world.

Despite their prevalence in other forms of media, such as Easy Rider, the “road trip” is a concept that few games attempt. Why do you think that is, and how did you work to embody that in Wheels?

Video games really struggle to blend gameplay and story, and this is not new — I’m not the first person to say this. Go to any GDC [Game Developers Conference] and you’ll see this topic being discussed. One of the reasons is that the ways storytelling takes place, it’s hard to make those interactive, and integrate them in traditional forms of gameplay that we’ve been learning to make for thirty years. There are strong limitations. One of those is, of course, how do you make a character that’s playable when your political opinions don’t align with those of the character you’re playing. Everything in Wheels is an experiment, an attempt to make this happen. The reason that there aren’t more games like Wheels is that it’s very risky and there’s no frame of reference for doing this. Some people even say it’s impossible.

Sounds like they’re wrong.

Well, they might be wrong, they might be right. Until there’s a pop success, itll be debated. Maybe you could argue [Inkle Studio’s] 80 Days was that success. It’s a very difficult problem.

What would you say is Wheel’s ethos?

I don’t think it really has one. It doesn’t really take any of the character’s motivations and history as its own. Even though Lella (the protagonist) thinks that racing and driving fast are part of her ideals in life, the game makes fun of it. I don’t think I ever really thought about the game in that sense. I’m more, how do we make it feel natural, fun, not too boring or serious. How do we represent travel itself? That’s the objective of the game: How can travel be an expression of a country?

Are there any particular works of media that influenced the development of Wheels?

I would say Il Sorpasso was the movie that single-handedly inspired it — the main reference.

Can’t say I’m familiar.

It’s basically about a road trip that takes place ten years before Wheels. Two men go on a trip. One is a very extroverted man, and one is very shy, and they clash and influence each other.

Naturally, as a narrative game, it features a constellation of different endings. Did that present problems during development?

I didn’t write the story behind the game, but I did tell the writers what I wanted regarding the variety of input, so that the player felt that their full breadth of actions were being reflected in the story. We wanted every dialogue choice to be meaningful on a story level, which ended up producing many, many endings. But the storyline isn’t written in a traditional branching path — it’s based on topics that the characters have brought up in the past.

Some of the response to Wheels has focused on the educational qualities of the game. People just don’t know that much about Italy, me included. Did that influence your design?

We always knew that we were making a game that would be perceived differently depending on where you grew up — the Italian public especially. The farther you get from Italy, the more exotic it seems. The French can sort of understand it, the Germans too. But when you come to the U.S., people usually freak out when they learn that our ex-Prime Minister was kidnapped and murdered.

We knew that this was going to happen, and we wanted the game to be a sparkle for renewed interest in the time period, so they would do their own research. We 50% succeeded in doing that — half of players would read into it, and the other half would just give up. So in a new update, we’re planning to include an in-game encyclopedia.

You mentioned the narrative structure is non-traditional. Do you mind speaking more to that?

Each line in the game is represented as a topic in the coding language, and each topic is tied to every other topic. And certain topics won’t come up if other ones haven’t come up, and vice versa. And each line has a priority, so if we’re chit-chatting, and we pass by a monument in the road, then that topic will become available, because it has higher priority than the existing topic.

That’s a really cool system. It must have been really hard to implement.

It was designed by us with Anna Kipnis, who works at Double Fine. She designs narrative systems for them, and she’s extremely capable. Not something we would have done without her.

What was the hardest part of the game to get right?

For sure, the blending of talking and driving. When we released the beta last year, we got a lot of critiques that called it a “texting while driving” simulator, meaning while they were choosing dialogue, they were hitting guard rails. Though the game doesn’t penalize you for this, it was unnerving and stressful to see your car go off the road. So in the current version, the car auto-drives, except when you accelerate. It was just a lot of design, but I think we were partly successful.

'Wheels of Aurelia' is just as pretty at night.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.