'Black Mirror' Will Make You Fear Streaming 'Black Mirror'

The third season is preoccupied with data collection, both voluntary and involuntary

Whenever it is mentioned to me that my behavior online (and thus, my activity in the real world) is likely being monitored by the government, corporations, and hackers, I wonder if my Big Brothers are enjoying all those deeply boring Google searches and Amazon cart updates. This is how I choose to think about data theft and, yes, it’s a quasi-clever justification for idiotic self-denial, one triggered by a feeling of fait accompli. Secret courts grant vast powers to the NSA. Overlong Terms & Conditions pages grant tech companies the right to metadata. I search for a Godzilla Blu-ray, and it follows me around for weeks.

My indifference to surveillance is demonstrably not unique. Everyone is uploading their most precious information for evil people to steal and exploit all the time; it is very much routine at this point, and I hardly even flinch at it. This is a very bad thing, but it’s hard to viscerally understand why without examples of real consequences. The solution to this problem is, at least for the moment, Black Mirror, the Netflix series that dramatizes the panopticon. I’m being watched and I care more because I’m watching the show and seeing just how dangerous that can become.

British writer/producer Charlie Brooker first launched the dark, cautionary anthology series in 2011, offering one-off commentaries on our modern weakness for cheap thrills and reliance on technology. In the first two seasons, released as mini series, Brooker imagined near-futures in which slight technological advancements created terrifying ramifications. In the latest batch of episodes, which debuted over the weekend, Brooker’s light dystopias are even scarier because they are less speculative than seemingly inevitable, and in some places, indistinguishable from what is likely happening in the present day. And while each episode has several cautionary tales and concerns baked into it, the connective tissue this time around is what we give up when we live our lives — both public and private — online.

The new series’s longest episode, “Hated in the Nation,” is structured like a cyber-crime thriller, a CSI with brains and a bleak outlook on humanity. On first blush, it’s focused on internet outrage and mass bully culture; Twitter users are empowered to execute one person a day via the world’s most dangerous hashtag.

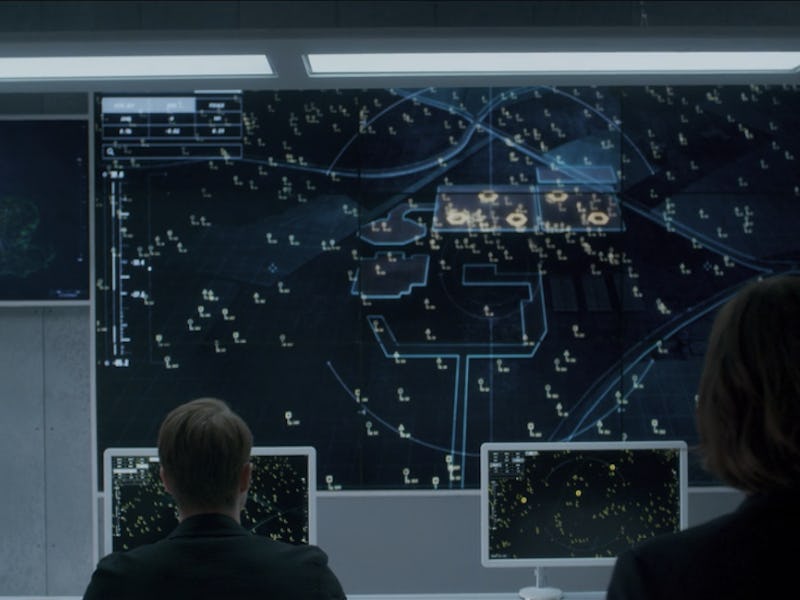

Like all Black Mirror episodes, it does not take a particularly kind outlook on man’s pack animal instincts. But grafted onto the episode is a seemingly disconnected B plot about honeybee drones, which have been developed and activated across the UK to do the crucial pollination work left untended by the nearly extinct insect. They are part of a massive program, the sort of forward-looking environmental works package you’d never expect a government to pass these days on its merits alone, and indeed there was a catch: The bees can and do record everything they see, providing the government — and hackers — with a bottomless well of information about the populace. Every person’s every move is monitored, and when the bees are weaponized, no one is safe.

This is the most straightforward example of the new Black Mirror’s preoccupation with data collection, but the larger concern that we give ourselves away — whether we know it or not — can be found at the core of each new episode.

The episode “Shut Up and Dance,” which is set in the present day, offers a seedier but no less disturbing scenario: The webcams in our phones and computers being secretly activated by foreign hackers, who then record our every move until they find something that can be exploited for blackmail. The victims in this episode are a young teenager who gets caught tossing off to porn and an otherwise responsible dad who tries to set up a tryst with a younger woman. We can tsk tsk each of them — especially the older one — but few phones are left out of our most intimate and vulnerable moments nowadays. In this case, not only do people know where we are and perhaps who we are texting, but they also have eyes on moments we would very much prefer to stay private.

Mind control through data collection — and direct inputs — also features prominently this season. In one episode, the army implants chips in soldiers’ heads so that they can have an advantage on the battlefield, as seemingly infinite information is overlaid on their corneas. It makes them better killing machines, but it also bends their morals by changing the way they literally and figuratively see people. As humans continue to experiment with physical optimization and cyborgization, they will continue to give over access to their brains. There is no scarier data collection than that.

Even in its scathing critiques of social media, Black Mirror focuses on the power of our own information, and what nightmares giving it out can create. “Nosedive” creates a world in which selfies and food Instagramming are a gateway to total dependency on the approval of strangers. Every interaction is logged and rated, and we live and die by our scores — quite literally, as access to homes and medicine become determined by our rating out of five stars. What is voluntary now has become compulsory in this future, and if you don’t think Facebook isn’t looking to integrate its services with every aspect of daily life, go get to know a lobbyist or two. This episode reads as a business pitch with some kinks to work out more than cautionary tale.

It’s the same thing for “Playtest,” the episode about virtual and augmented reality — here, gamers allow a small device to plug into their cortex to read their thoughts and create more personalized experiences. A secretive gaming company is running trials on volunteers, who are all stoked to see behind the curtain (blame sites like TechCrunch for turning these power-hungry nerds into gods). They sign away their lives so that this company can better calibrate just how it roots around their brains — to create a more fun app, of course.

It is ironic that the show is now being put out by Netflix, of course, because Netflix is a gigantic data collection company that knows more about your viewing habits than you do, and never releases the mathematic insights it collects.

By the way, please like Inverse on Facebook so that we can collect and better understand the demographics of our readers, and thus customize our content and sponsorship deals to optimize their effectiveness.