How the 'Westworld' Laboratory 3D Prints Robots and Realism

Inside the design of the robot hosts and the advanced lab that makes them

If HBO’s Westworld took place entirely in the fictional, period-perfect theme park from which it borrows its name, the show’s production designers and visual effects crew would have had an easier job.

That’s not to say that creating an artificial Western town is easy. It isn’t. But creating a realistic android production facility that functions in a consistent, credible way is crazy hard. And that’s what Dr. Robert Ford’s underground laboratory is. It looks and feels real because the machinery of creation was tirelessly specced out and, in some cases, put to real use.

This was a complicated task, but production designers Nathan Crowley, who worked on the pilot, and Zack Grobler, who took over for Crowley, agreed on one overarching principle with a VFX team led by Jay Worth: Keep it simple. The robots were the main attraction, and any suggestion that they were not created by a kind of vaguely recognizable technology would take away from their believability.

“The design of the lab had to be clinical,” says Grobler. “With the biological and the medical world, you also start to have to get cleanliness and you have to get medical facility has to be quite clean. I did like the idea of the contrast between the above and below.”

A small part of the lab

The underground set was roughly one-hundred feet by fifty feet, according to Grobler. And it was designed with restraint. The glass-walled rooms and everything in them had to seem cutting edge, but the designers couldn’t go too far with it — this was a show steeped in science, not magic. They were, in effect, vaguely futuristic factories, with 3D printers working like they do today. “Some things haven’t changed for hundreds of years,” Grobler points out. He didn’t want to create something aimlessly futuristic.

The most science fiction-y-looking prop in the lab is a holographic rendering of the park that workers use to zoom in on the action. And even that, advanced as it seems, was conceived of with an eye toward realism — the base itself was physically built and rotated, with only the moving images on top created through computers.

“We had to build a CG projection that was projected with 4k projectors,” says Worth. The image and platform all rotated in sync. To figure out how to have a thing that’s not illuminated from beneath, but has 3D quality, but is not a hologram or a knock-off holograms, that took so much time.”

The team took a similar approach with the work tablets used by many of the characters. They show 3D projections, but they do so in a way that feels like a logical outgrowth of current augmented reality technologies; they look like something security guards might have in 20 years.

There is a sense of evolving technology, one that bleeds over into the construction of the robots themselves.

While the robots in the show are all played by real actors, the conceit is that underneath those seemingly human exteriors, there are ultra-advanced synthetic organs that mimic internal kidneys, intestines, and hearts without actually serving the same functions — the robots die over and over again, but never of natural causes. To design the underground manufacturing and maintenance complex where they were made, as well as the machines that did the heavy lifting, the team had to figure out now only how the robots were pieced together, but how that process evolved over time.

“At first they were printing the robots and making them with typical parts,” says Gobler, “but then later it became more biological.”

This is reflected when, on the show, viewers see flashbacks of earlier production units and the remains of bots with C-3PO-style innards — they look like the cover of science fiction novels from the 1950s. Now, to illustrate the huge leaps taken since the robotic parts in the flashbacks were made, the muscle fibers we see installed in modern hosts were created using CG.

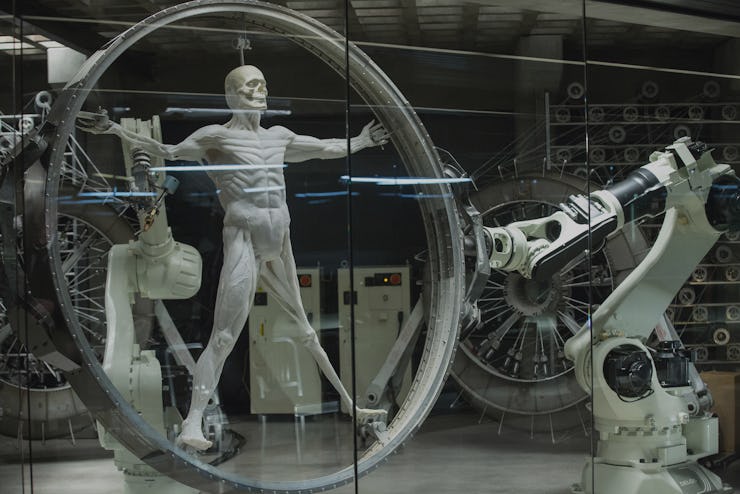

The muscle fiber machine

Right now, the hosts are all organic, explains Worth. “That’s something we talked about at the beginning, how much easier it’s going to be because theyre supposed to look like humans on the inside. We have a scene in the pilot with Dr. Ford [Anthony Hopkins] and Bernard [Jeffrey Wright]. We have them in what we call the muscle weaving room, where we see the fibers get stretched out on the these bodies, and the skin dip.”

The series’s logo features a pure white robot model stretched on a circular rig, a new-age rendering of Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man pose. On the actual show, the process of creating that flawless body is a little bit more involved and a lot messier. Viewers can see androids being dipped in vats of pure white liquid, their skeletons and musculature covered in a dripping human-like layer of simulated fat and skin.

“The dipping effect was practical,” says Worth. “It was a glue and water substance that just looks awesome. That’s the fun thing about it, you really don’t know what’s practical and what’s not. We had these huge robot arms and muscle fibers, which made for a fun playground for all of us.”

The third episode, airing Sunday, gets into the nitty gritty of the organ-making process, including the intricacies of making eyeballs. Much of it was done with practical effects, planned out via trial and error.

“I had all these ideas about how the eyes were made and was really trying to get a sense of how would an artist make it and how would technology make it?” says Worth. “It was fun to figure out how to get the pigment in and how to get the white viscous substance in first. Then to stretch the strands of the iris across and to have it feel like almost a printed tattoo, but also weaved. We thought about all those little bits of technology to figure out how this could happen in a way that you would end up having something that was organic or did feel organic.”

And even though the show spends less time dwelling on the manufacture of gall bladders, that doesn’t mean the crew didn’t think about it or create laboratory space for that job. If you have a question about the host anatomy that the show hasn’t addressed on screen, fear not: They have an answer for you, anyway.

“There’s an organ printing room and an organ stuffing room, there’s an eyeball section, then there’s the muscle fibers and the skin dip and the pigment,” says Worth. “There are so many rooms we thought about because, even if we’re only showing a small sliver of it, to make it feel like it’s part of a larger world.”

And the microcosm of that larger world lies at the heart of the laboratory. Dr. Robert Ford’s office is cluttered with bones, real and synthetic, character masks and photographs hinting at a life he once had. It’s a bit chaotic and, despite the glass walls, as opaque as the character himself.

“He’s the creator of the world, of the park, he has imagined every little detail, and also created the robotics and technology,” Grobler said. “But it’s almost like he was a child fifty years ago and he had all these fantastical ideas about the Old West and in the future some of those got lost. It’s his way of lovingly recreating these beautiful little icons and these little moments. I wanted to fill his whole office with little pieces of that world that showed how he does it, that he’s more tangible and he’s more of a craftsman.”

The final result, which is featured in the third episode, is their best answer to an impossible question: “What does God’s office look like?”