Thanks, 'Hunger Games': Why Cautionary Sci-Fi Isn't Fun Anymore

Because dark dystopias are no longer unimaginable, a whimsical gap has closed.

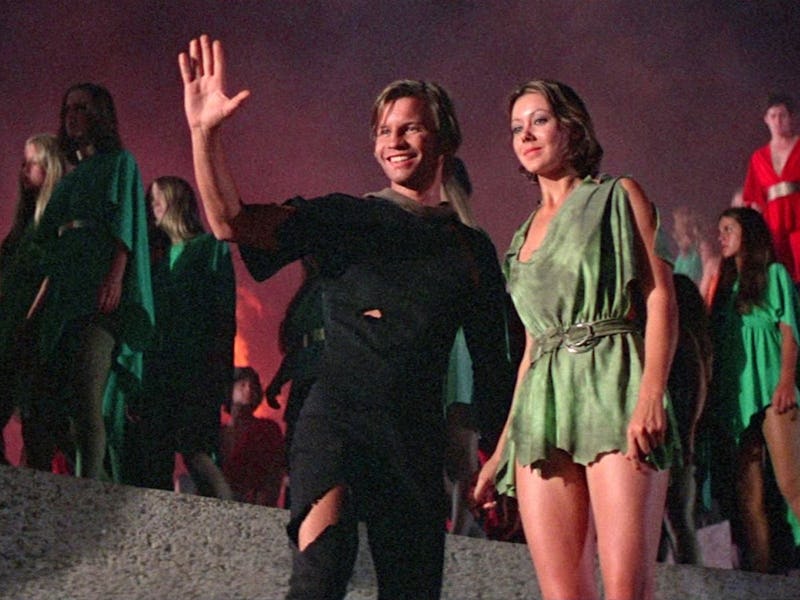

In the 1976 film version of Logan’s Run, a dystopian 23rd century world murdered its citizens simply because they turned 30-years-old, and it was totally hilarious. While Logan’s Run took its premise seriously, part of its appeal was directly connected to built-in kitsch.

Once a staple of social science sci-fi, that kind of fun self-awareness in dark stories about the future is now a thing of the past. Cautionary science fiction movies such as Netflix’s ARQ or The Hunger Games might be more grittily realistic than their sci-fi predecessors, but they certainly don’t have the sense of aesthetic whimsy of previous generations. And there are plenty of direct comparisons in this era of reboots: In the last half decade, both Planet of the Apes — a franchise first launched in 1969 — and Westworld (1973) have been recently remade for contemporary audiences. Though we could debate endlessly if these efforts are “good” or “worthy successors,” both are decidedly way less fun then their progenitors.

Newer cautionary tales are certainly rendered more convincingly and this “dark” sci-fi is obviously more realistic. But does that make it more entertaining?

“One’s sense of fun concerning a science fiction/fantasy cautionary work is a matter of perspective,” Diana Pho, an editor at the heavyweight sci-fi and fantasy publisher Tor Books, told Inverse. “Robocop is fun,” Pho continued, “but it can also feel more biting if you’ve dealt with police brutality or lived in Detroit during the ‘80s through today.”

Cautionary science fiction is often set in a dystopia, a fictionalized future world in which everything is totally fucked. Defined broadly, dystopian sci-fi could encompass the vast majority of all popular science fiction movies, including Star Wars. But author Margaret Atwood, an undisputed master of writing convincing dystopias, instead coined the word “Ustopia” because both utopias and dystopias “contain a latent version of the other.”

Narratively, this is a no brainer: Any full-on dystopia like Mad Max or Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy has central characters longing for a more ideal world than the one in which they live. The ending moments of the final Hunger Games novel, Mockingjay, depicts Katniss trying to build a small utopia from the ashes of a brutal dystopia. Atwood thinks all of this connected to how much we can buy this bleak fictional setting. Writing in her book In Other Worlds, she says, “Unless we readers can believe in the ustopia as a potentially mappable place, we will not suspend our disbelief willingly.”

These days, dark science fiction settings barely require us to suspend our disbelief at all. With a movie like ARQ, we’re introduced to a world that has an energy crisis and a government that spies on you. If it weren’t for the introduction of a time-loop into the plot, this movie wouldn’t really seem like science fiction. In the post-Snowden era of government admitting that it spies on its citizens, any story such Orwellian hand-ringing would be annoyingly cliché if it weren’t so damn realistic.

The only difference is that in our real world, Big Brother isn’t simply a creation of the government or nefarious corporation; while their data is being monitored, everyone is already willingly giving up their privacy via social media, camera phones, etc. Buying into a movie or show that depicts a “future full of surveillance where you should be afraid of the government” is something our imaginations can easily handle, because almost no imagination is required; in fact, these fictional worlds exonerate us from any guilt we might feel for making it so easy to spy on us.

'Gattaca'

In his 2014 book Outer Limits: The Filmgoers’ Guide to the Great Science Fiction Films, author Howard Hughes writes, “The gulf between ‘best’ and ‘worst,’ while wholly subjective, is more apparent here [in science fiction films] than in any other film genre.” And our filmgoing and television watching standards for what constitutes “good” and “bad” in science fiction have decidedly shifted into a neat and binary paradigm: Dark is critically “good” and everything else is “fluff.”

What this results in is that almost none of the human characters in the new Westworld are likable. Meanwhile, the vasty majority of the humans in the newer Planet of the Apes are similarly power-hungry or awful. Sure, these films and TV shows aren’t advocating the abolishment of the human race, but they sure are lecturing us a lot. Writing for the Washington Post, Hank Stuever even felt like the heavy-handedness of the new Westworld was a “homework assignment.”

But science fiction films and television are more than just glib finger-wagging warnings about the future. They can be artistic, too, right? The 1997 film Gattaca is certainly a depressing Orwellian world, but the film itself is beautiful. These days, the minimalist aesthetic of Gattaca doesn’t work by itself, and has to be jazzed up with some “realistic” darkness, which is exactly why we’re getting a new SyFY Channel TV show called Incorporated, which looks like Gattaca for the Occupy Wall Street generation. Beauty and design in Ustopias is out, a new type realism is in. But, beauty and humor are found in the real world. Do they no longer have a place in dark, gritty sci-fi?

“Science fiction and fantasy, has, in general, tried to make itself more mature and sophisticated and literary in recent decades,” says Marco Palmieri, an editor at Tor/Forge who also used to edit Pocket Books Star Trek novels. “But humor isn’t absent altogether.”

Humor is tied to hyperbole, but then again, so is satire. Three decades ago, one might have watched Westworld or Logan’s Run or Planet of the Apes and taken the films very seriously, at least as abstract metaphors. Now, we get an extra kick out of retro-dystopias because their cautionary metaphors seem super urgent. A world in which people are murdered for being over 30 à la Logan’s Run seems silly, whereas a world of constant government surveillance is highly plausible. Logan’s Run is fun to watch, ARQ, less so. Meanwhile the fun jury is hung on the greedy rich people who like to screw and shoot-up robots on the new Westworld. Sure, that dark sci-fi future seems realistic and well-drawn, but has none of the goofy charm of the original.

Hope for fun and quality can be found in all of Mad Max though. Despite the original film being over 30 years old, the post-everything, resource-devoid world of the Mad Max fictional universe still seems fairly feasible, assuming we ignore the outrageous guy with the flame-guitar in Fury Road. Perhaps here is the most obvious perfect synergy of dark cautionary science fiction and entertainment-driven cinema. No one would actually want to live in the future world of Mad Max anymore than you’d want to live in the world of Logan’s Run. But the experience of watching Furiosa liberate a harem of slaves and Max driving cars fast while growling is, on some very basic level, fun. Correctly, the almost universal praise of Mad Max: Fury Road has focused simultaneously on its politics (it’s a “feminist” story) and the artistry of the movie itself (it’s a “beautiful” film). Both of these things are true: the movie is decidedly relevant while being wildly entertaining at the same time.

So, actually, don’t ignore that that guy with the flames coming out his guitar in Fury Road, because he’s great: He’s a glimpse of that leftover kitsch from Logan’s Run or the original Westworld, recalling a time when cautionary science fiction could have its preachy cake and eat it too.