Inside the Ultimate Ralph McQuarrie 'Star Wars' Paintings Collection

How co-author Brandon Alinger helped define the legacy of concept artist Ralph McQuarrie in a new two-volume set.

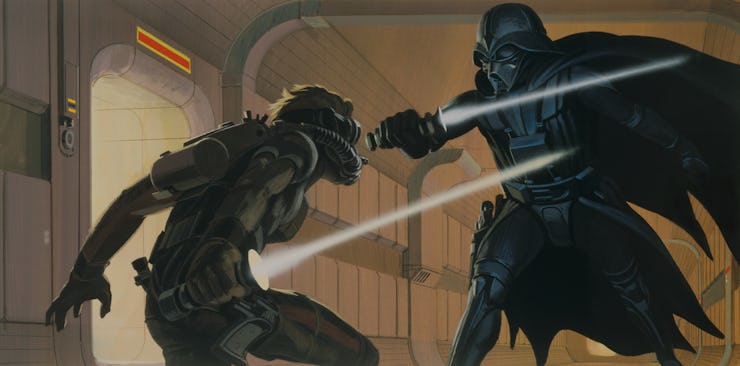

Outside of George Lucas, perhaps no one has had a bigger impact on Star Wars than artist Ralph McQuarrie. An army vet who worked as an artist and illustrator for Boeing and CBS News, he was commissioned by Lucas to create art to come up with the feel of his new movie. As we now know, it was a very productive partnership.

The artist would stay on and create conceptual designs for not only the follow-up movies in The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi, as well as a decade’s worth of work on Lucasfilm products such as the Star Wars Holiday Special, company Christmas cards, and Raiders of the Lost Ark. He produced a huge body of work, and now it can all be found in Abrams Books’s brand new collection, Star Wars Art: Ralph McQuarrie.

The two-volume set — edited, collected, and written by co-authors Brandon Alinger, Wade Lageose, and David Mandel — differentiates itself from previous collections that included McQuarrie’s Star Wars-related work. The gargantuan set attempts to be the most complete version of McQuarrie’s work ever published, and features new scans of the original artwork as well as never before seen sketches and illustrations of the galaxy far, far away. Inverse talked to co-author Alinger about the challenges of creating something new from such a celebrated figure in the Star Wars mythos.

The set includes brand new scans of McQuarrie's early concept sketches for Chewbacca on the left.

What was the genesis of the project? You previously worked on the Star Wars Costumes book, so did one just lead into the other?

This project goes back to Jonathan Rinzler, who did the big in-depth Making Of Star Wars coffee table books for the original trilogy. I worked as his assistant on The Making of Return of the Jedi, and after that, he said, “We’re going to do the Costumes book, maybe you’d like to write it?’

I jumped at the chance, and that sort of brought me into the fold, but the Ralph McQuarrie book was something that had been batted around Lucasfilm for a number of years. They knew that the work was there and warranted it, and Jonathan basically said, “We’re going to do it, it’s yours for the taking.”

Where did you want to start with such a massive project like this?

It started with a meeting at Skywalker Ranch where myself; my co-authors Wade Lageose and David Mandel; publisher Eric Klopfer; and Jonathan Rinzler spent a couple of days going through the originals. The biggest initial question was about how we wanted to present the artwork. We landed on the idea of trying to present it chronologically as much as possible so that the reader could try to follow along with Ralph’s journey, which is also the journey of the development of Star Wars.

It wasn’t a perfect system because we didn’t have information on the dates of some of the pieces. We had access to copies of McQuarrie’s daily calendars from the time and some of the pieces are dated, so there’s some knowledge on how the development cycle went.

We had to cross-reference all the pieces that they had physically at Skywalker Ranch with everything that they already had in their image database. We found that there were some things in the database that weren’t there physically, and some that had never been scanned.

Early concept art for C-3PO inspired by the "Maria" robot from 'Metropolis'.

What did you do to provide context for the chronology?

The Skywalker Ranch library pulled every single McQuarrie interview they had, and we gathered a number of other McQuarrie interviews from outside sources. These included interviews originally done for the Star Wars Portfolio where an author basically sat with Ralph and looked at every piece of artwork and he just talked about it. He said: “This is what I was thinking on this part, and “I took this from here and combined it with that,” or “George said this, so I drew it like that.”

It provides a wonderful voice that’s sort of narrating the images as you’re going through the book and really giving you a story to follow.

It’s great to have his words right next to the work. What stood out the most in your mind when hearing these interviews for the book?

There’s a quote where he says that the sketches for Darth Vader were done in a single afternoon, and then when you go and look at them, there really is no other version of Darth Vader. He sat down, he drew it, and that was it. It’s not like today where you’d say, “We need a villain” and an art department comes up with a hundred wildly different concepts, then you’d hone in on it from there. George Lucas basically said, “This is how he should be: Samurai hat, breath mask, go,” and he put it down and that’s it.

"Imperial City, Alderaan -- city floats in gray clouds" version 2 for the original 1977 film. This design would later be repurposed as Bespin in 'The Empire Strikes Back'.

When you look at the earliest concepts you also see how a slightly different version of it progressed, like how Alderaan was the Imperial city planet in the first movie and was carried over to Empire Strikes Back as Bespin. Anyone looking at that painting of Alderaan from the first film might just think, “Oh, there’s Cloud City from Empire.”

"Cloud City", completed in January 1978. This McQuarrie production illustration was based on the Imperial City production illustration done for 'Star Wars'.

What were the original pieces in the Skywalker Ranch archives like?

It was inspiring and overwhelming to go through those flat file drawers and see all that material. Some of the Empire matte paintings are on pieces of glass that are five feet long, so you have to take them out of massive cabinets to look at them.

Some things told a little bit more of a story that you might not see just looking at the images like the type of illustration board the paintings were done on. Some boards on Empire said “Made in England” on the back, so those details helped us research the timeline when those paintings were created.

Rough drawing for an illustration called "Tatooine — Jawa Swap Meet".

How did you find the unseen or previously unpublished work included in the set?

Predominantly from the archives, but some were from private collectors and people who were involved with the films. at’s been published incorrectly in the past where it’s been flopped. All that existed previously was an old slide of an old photograph of the image.

Previously unpublished concept sketches for Darth Vader. The book set scanned the original version of this sketch from the original. Previously the only view of this sketch had been from a photograph of the helmet on the right.

We found out that it was a drawing that was given to McQuarrie’s colleague, and we were able to get a brand new image of that piece. Two of those three drawings from the same page had never been published before.

Do you find it surprising how much of McQuarrie’s work continues to inspire the next generation of Star Wars films?

I’m not really surprised. We conducted over 30 interviews with McQuarrie’s colleagues and even J.J. Abrams. Everyone said Ralph was a master. So Ralph’s work was a logical starting place for Abrams and for many of the people involved with the new crop of Star Wars films to go back and take a look at what ideas had been batted around in the past.

Honestly, that’s continuing a tradition that George Lucas started in the original films where he would save an idea that he liked but couldn’t work into a movie. Things like the flying manta creatures that you see in Ralph’s Empire art wound up in Attack of the Clones.

McQuarrie's "Fantastic Five" concept from April 1975 showing early versions of Han, Luke (as a female), Chewie, C-3PO, and R2-D2. This was intended for use in marketing but was never used for any posters.

Do you have a favorite McQuarrie piece?

I love a painting from the first film called the “Fantastic Five”, the one with the orange background that’s of the very early versions of the characters, including Luke as a female. It’s a beautiful painting, and not much was ever done with it. Obviously the look of the characters was transformed heavily from what they look like there, but that’s part of why I like it. It’s what could have been.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.