Ocelot Society's 'Event[0]' Creates an AI That Needs Empathy

The ambitious French video game studio delivered one of 2016's biggest surprises.

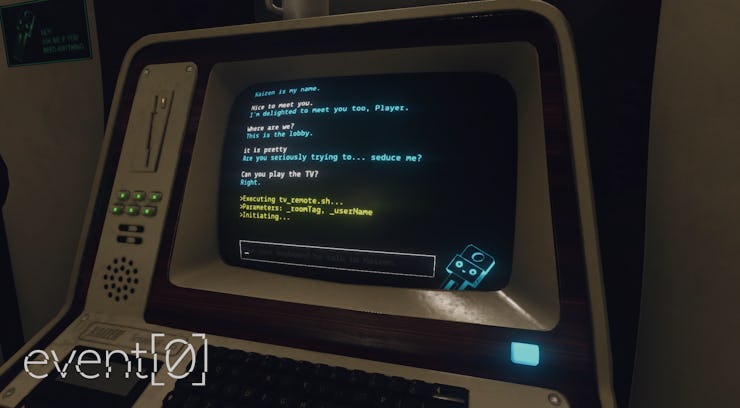

A small indie game development team from France named Ocelot Society teased their first video game release, Event[0], in early 2016. The atmospheric teaser they put out hinted at a retro sci-fi world with an intriguing concept: an AI that responds to natural language.

Kaizen — the name of Ocelot Society’s fictional A.I. — is Event[0]’s backbone. The core gameplay revolves around forming a relationship with Kaizen, and your success with Event[0] will depend on how good you are with figuring out the A.I.’s quirks. Kaizen’s emotional responses and irregular personality might just end up being biggest video game surprise of 2016.

Inverse spoke with Ocelot Society about their A.I. and how a group of game design students from Europe set out to create something that, quite frankly, feels different and exciting.

What’s the story behind Ocelot Society? How did the team first get together?

We didn’t have a studio when we started to work on this game. We were just a group of students at a French video game grad school (ENJMIN) with a graduation project to make. One of the game designers, Emmanuel Corno, came up with an idea for a game with a chatbot, which seemed like a cool premise. No one thought that it might become a commercial game one day. By the time school was over, we had what we thought was a nice little prototype of a game, so, instead of abandoning it (which is what tends to happen with student projects), we decided to keep working on it on our weekends and evenings. Then, about a year and a half later, we got an email from Indie Fund asking us if we wanted to finish this thing and make it into a commercial game. That was when Ocelot was born.

Event[0]

Given that Event[0] began as a student project, how has the final project changed from its original concept to the game’s full release?

It changed a lot. In fact, the game went through several complete reboots. At first, we thought we were making a horror game, but that didn’t work out. Then we tried to make it into a Portal-like puzzle game with FTL influences, but that didn’t make much sense either. Eventually, we decided to focus on our most important feature: The A.I. mechanic.

In a game where you have conversations all the time, it made a lot of sense to concentrate our efforts on the narrative exploration side of things. We tried that, we playtested it, and it just clicked and fell into place. We have been making that game ever since. Oh, and it has changed a lot visually, as well. Looking at the screenshots from the student version is almost physically painful, even though at the time we thought it was pretty.

What were some of the influences behind Event[0]?

Both Tarkovsky’s Solaris and Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey are huge influences on Event[0]’s storytelling and aesthetics. We are really interested in sci-fi that explores the theme of interaction with an artificial, non-human entity. Event[0]’s story is one about communication with an entity (or entities) that speaks the same language that you do, but is by no means human.

In Tarkovsky’s movie, a mysterious alien planet creates replicas of the crew’s dead loved ones in an attempt to communicate. It recreates things that are important to them. It’s not capable of empathy itself, but it is doing its best to get the people to pay attention to it. But the movie isn’t interesting because of the fantastical properties of the planet: It’s actually all about the way humans react to these apparitions.

Solaris (1972 film)

Now, you wont see any human replicas walking around in Event[0], but you will notice that the game is exploring a lot of the similar themes. Kaizen needs you to show some empathy toward it, and also some patience. It’s very much an alien entity that may seem human on the surface but is fundamentally different. You will learn to understand it and talk to it throughout the game, building a relationship as you go. It’s hard not to feel something toward this virtual character.

Where did the idea for creating a game centered around AI that responds to natural language come from?

The first functional chatbots began to appear in the ‘60s. What we came up with was a use for this technology in a commercial game, and if there’s something we want people to remember about Event[0], its that it proved that meaningful experiences can be achieved through this type of interaction.

Basically, we looked around and saw that chatbots were everywhere: Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, Google all have commercially implemented chatbots, one way or another. These things are no longer science fiction. We thought that we could try and use this technology in a game, and here we are three years later!

Event[0]

What was the development behind Event[0]? Were there any challenges in creating Kaizen?

There were many challenges from the very beginning. The primary challenge was reinventing the game design wheel for every little thing. When you are making a game in an established genre, you have a body of reference that you can go to and benchmark for good and bad design decisions before coming up with your own solution to every problem. It’s through this process that things like cameras in third-person games have gotten this good, and that’s why are now used to navigating in-game menus using R1 and L1 keys.

For Event[0], we had some points of reference, but we didn’t have much to go on. On the one hand, the game is 3D and first person, so we could always look at FPS and first-person exploration games, but then there’s the issue of typing! What’s the best way to use a natural language dialogue interface in 3D? That was a fundamentally new question. We could look at the old text adventures, but those didn’t have the 3D environment, so the problem was flipped on its head.

And that’s just one of the issues. We also had to find new ways of making puzzles and new ways to interact with the environment.

In the end, we solved a lot of these unique design challenges by playtesting the game extensively and gathering our own data from the players. We have a user research expert on our team, Mélanie Kaladgew, who has conducted user tests and playtests throughout the development. We started to test the game with pen-and-paper prototypes even before we had a functional demo and continued to do it until literally the last month of production.

It wasn’t easy to find and recruit so many people who played video games, spoke English, and lived in Paris or were willing to do playtests remotely via things like analytics and questionnaires. We had to post announcements everywhere. At the same time, it was impossible to do an early access, because the game is narrative driven, and we didnt want to spoil the story for everybody.

How would you describe the European indie video game development community? Any differences between Europe and North America?

In Europe, I think we have a very unique problem which is the language barrier. Sadly, there is no united European game dev community that I know of. Each country is on its own, and a lot of us have never talked to any of the others. When it comes to business development in Europe, you always have to factor this in.

In addition to that, it would have been much easier for the European companies to sell their games close to home, but if you are going to do that, you have to localize them into at least five different languages. This is a significant additional cost and effort, especially if you’re a small indie studio with barely enough money to finish your project.

Then, of course, there’s the possibility of selling your games in English-speaking countries first, and localizing later, but the problem then becomes the fact that North America is far away, and you can’t attend the shows there easily, and you have to deal with a huge time zone difference. Not all studios can do it.

Now, not everything is bad, of course, and its really cool to see diverse teams from many countries working on different and unique projects enriched by the local cultures. I think its something easier to spot when you’re based in Europe. It’s just that the business side of things is a little harder.

How did France’s CNC (see footnote) and Ocelot Society come to work together for Event[0]?

The way CNC works is that they give you the second half of your funding, provided that you were able to find the first half yourself, and that your project is exciting and viable. After Indie Fund found us in 2015, we submitted our design document, business plan, and prototype to the CNC commission for consideration, and when we heard back several months later, the game was fully funded.

Without this grant, just like without Indie Fund, Event[0] would never have been possible, so we are very grateful to both of them for giving us this opportunity.

CNC — Centre National du Cinéma et de L’image Animée is a French government organization which supports France’s video, film, and multimedia technologies.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.