Museums are full of books that can be destroyed if they aren’t handled properly. Preserving these artifacts is important, but figuring out what they might reveal about the past could also be valuable, so researchers at MIT and Georgia Tech found a way for historians to have their fragile stacks of paper and read them too.

MIT Media Lab developed algorithms that use terahertz radiation to detect images on individual sheets of paper that had a single letter printed on them before they were stacked on top of each other. Georgia Tech wrote the algorithm that analyzes those images to figure out what letter was printed on each page.

The latest prototype of this method, which is described in the latest issue of Nature Communications, is capable of peering through nine sheets of paper at once. Although the tool’s usefulness is limited, it proves that the concept is sound.

MIT researchers and their colleagues are designing an imaging system that can read closed books.

“The Metropolitan Museum in New York showed a lot of interest in this, because they want to, for example, look into some antique books that they don’t even want to touch,” MIT Media Lab researcher Barmak Heshmat said in a statement. He said that the tool can also be used on machine coatings and pharmaceuticals.

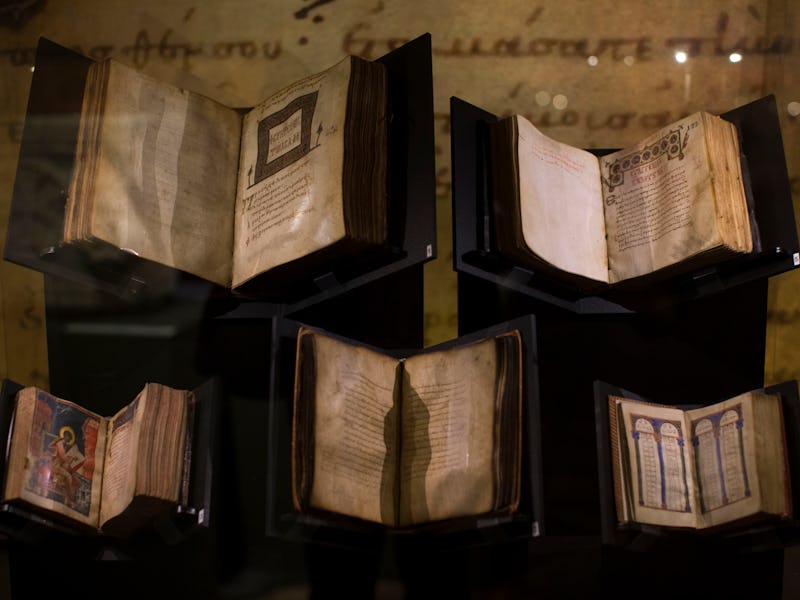

This system could allow historians to learn from artifacts too fragile to handle. The idea of losing data terrifies people — working with ancient books that can’t be replaced surely compounds that fear.

An image taken from the world's oldest polychrome book, which people were not allowed to open until 2015. While this book wasn't scanned using this new technique, similarly fragile books might one day be read using these technologies.

In the meantime, other researchers are finding ways to use DNA for data storage and creating five-dimensional glass discs that should last billions of years so future archivists won’t have to worry about paper’s ephemeral nature.