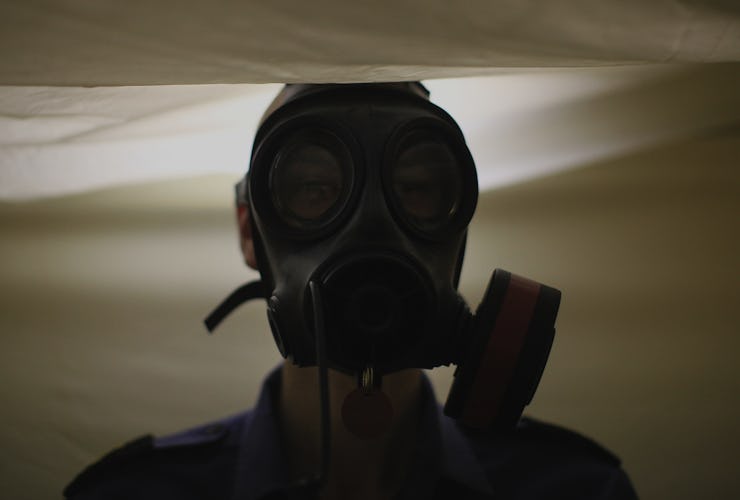

A Chlorine Gas Bomb Literally Burns Your Insides

The deadly gas seeps into lungs, where they're turned into tissue-burning acid.

On Tuesday, reports that the Syrian government had dropped chlorine gas on rebel-held Aleppo called to mind horrific photographs from the Belgian fields of Ypres, in World War I. Then as now, victims of the gas attacks are being treated in makeshift hospitals with emergency oxygen, their lungs severely damaged by the corrosive vapors. The efficiency with which chlorine gas incapacitates has not changed in 101 years.

Reports from Syrian activists and aid workers that government aircraft had dropped the poison gas on the contested city have not been verified, but medical reports from improvised Aleppo hospitals texted to Guardian journalists described a scene straight out of a European history textbook: Dozens of struggling patients, smelling of chlorine, with severe breathing problems and heaving dry coughs.

What they’re really suffering from is burns.

When a chlorine attack occurs, the most vulnerable parts of the body are the wet ones, biologically known as the mucous membranes: Because it’s a water-soluble molecule, the eyes, throat, and lungs are its passageway into the body. As molecules of the gas are inhaled, they seep into the lining of these organs, where some scientists believe they’re converted into acids. One study, published in 2010, suggested that chlorine gas reacts with antioxidants in the lung’s lining to create hypochlorous acid and hydrochloric acid, which are known to eat through tissue at high enough concentrations. As cells in the affected organs are essentially burned to death, those organs fail — hence, the increasing inability to breathe.

Because high-level exposures, fortunately, happen so rarely, treatment for chlorine gas inhalation remains badly defined. Tests on animals outlined in one 2010 study in the Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society have shown that breathing in humidified oxygen or vaporized beta-adrenergic agents — drugs sometimes prescribed for smoking-induced COPD — to be helpful as first aid treatment, but no antidote, or cure, to chlorine exposure has been found. That same study also reports that up to 1 percent of people exposed to high doses of chlorine toxicity will die.

In August, a United Nations inquiry determined that the Syrian government had been responsible for two similar chlorine gas attacks in 2014 and 2015. If the recent reports are accurate, and chlorine bombs were indeed dropped by warplanes sanctioned by the Syrian government, it’s likely that the scene was as devastating as it was on the fields of Ypres, as one British soldier’s account, quoted in a 2008 article on WWI chemical warfare in the American Journal of Public Health, described:

[I watched] figures running wildly in confusion over the fields. Greenish-gray clouds swept down upon them, turning yellow as they traveled over the country blasting everything they touched and shriveling up the vegetation. . . . Then there staggered into our midst French soldiers, blinded, coughing, chests heaving, faces an ugly purple color, lips speechless with agony, and behind them in the gas soaked trenches, we learned that they had left hundreds of dead and dying comrades.

At least 120 people are said to have been injured in the Aleppo attack. The Syrian government has denied its involvement.