Claustrophobia Remains Scarier than Morgan, Who is Terrifying

The new sci-fi thriller 'Morgan' is the latest in a long tradition of films that limit themselves to a single setting.

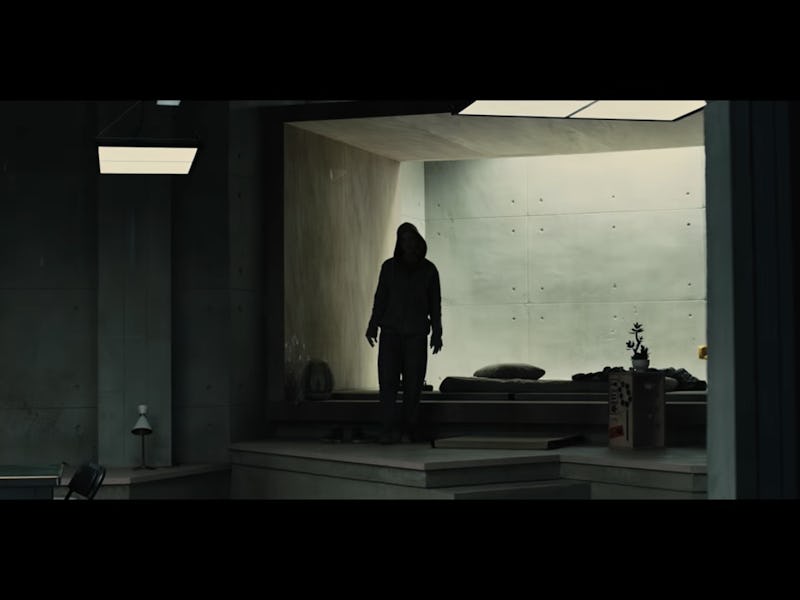

The plot for Luke Scott’s upcoming sci-fi thriller Morgan is deceptively simple – and the best thing it has going for it is the narrow, claustrophobic scope of its single-location setting.

The film follows a “risk management consultant” named Lee Weathers (Kate Mara), who is sent to an isolated scientific compound in the middle of nowhere to assess problems with the creation of a humanoid named Morgan (Anya Taylor-Joy). Once she shows up to shut them down, the scientists get testy, Morgan gets testier, and the tension is ratcheted up to allow room for subtextual questions about human emotions, imperfections, and all that good stuff.

Scott obviously took copious inspiration from his father Ridley’s 1979 classic Alien, whose main alien-versus-unsuspecting-humans action takes place in a dank and shadowy space freighter.

Putting your movie in an isolated setting like that offers up as many challenges as it does shortcuts: as much as huge blockbusters (like James Bond movies) are predicated on globetrotting adventures, it’s still somehow a bigger narrative test to think small. Like his father before him, Scott knew that by limiting the space of the action you make the story itself more creative.

It’s that reason why most single-setting films sound extremely boring when you try to explain their plot. Morgan is about a corporate stooge who has to figure out what’s wrong with a weird test tube baby her company created. It sounds a bit boring, just like how Reservoir Dogs sounds boring when you boil it down to saying it’s about a bunch of con-men arguing about a robbery gone wrong.

The clever twist in keeping the action focused in a single place is that it turns out to be more clever than if the story was given free reign. The main narrative strength of Reservoir Dogs is that it specifically doesn’t show you the robbery, and mostly limits itself to the character connections in a single warehouse. Its better because of that.

In the same way, isolated films make the storytelling method itself more creative. The grandfather of all single-location films, Sidney Lumet’s 1957 legal parable 12 Angry Men, which takes place almost entirely in a single jury room, stays fresh because its fluid camerawork and framing makes the gimmick of never leaving that room more than just a gimmick.

The same — with a little bit of leeway — could be said of the Colin Farrell-starring 2002 thriller Phone Booth, about a guy who must stay in a New York City phone booth or risk getting shot by a sniper. While not as prestigious or well-regarded as 12 Angry Men, or even Alfred Hitchcocks real-time faux-single-take thriller Rope, the idea to limit where a story takes place becomes the very impetus to tell it.

More often than not, the single-location motif is used in genre films like this because thrillers and horror movies need to inject a certain level of intensity that, say, comedies, don’t if they just happen to be set in someone’s apartment. The narrative demarcation that the film won’t let the audience leave a certain area is subconsciously claustrophobic. It becomes something to notice and be wary of because it goes against the way “normal” films unfurl.

It’s why Domhnall Gleeson’s innocent tech geek character wandering into Oscar Isaac’s bro-billionaire genius character’s isolated compound in Ex Machina is the perfect introduction of the anxiety of what will eventually happen there without even having the characters say a single word. It’s why even the extreme examples of this, like in Rodrigo Cortés’s Buried, where Ryan Reynolds plays a character who is buried alive for the film’s entire 95-minute runtime, skate by on the very idea of severe isolation on its own.

The master of secluded tension, again, is Hitchcock who used this kind of premise to his advantage over and over again. Rope, his 1944 Steinbeck adaptation Lifeboat, and 1954’s Dial M for Murder rely on their relatively isolated settings to simply allow the tension to simmer and then build to a climax. The pinnacle of the limited setting in Hitchcock movies is probably 1954’s Rear Window, where Jimmy Stewart’s photographer character is confined to a wheelchair and (like the audience themselves) can do nothing to stop a potential murder from happening across the courtyard from his Greenwich Village apartment.

The problem with Morgan is it fails to capitalize on its single key setting. It has all the makings of being the next in a long line of memorable sci-fi thrillers that take place in one location, but it never makes the compound or its surrounding environment anything other than a place for its motley crew of one-note scientists to prove they have no common sense. It’s just a scene where Morgan can karate chop Kate Mara’s character and escape when she pulls out a gun. Too bad. The movie could have done so much with so little.