How ‘Don’t Breathe’ Subverts the Home Invasion Genre

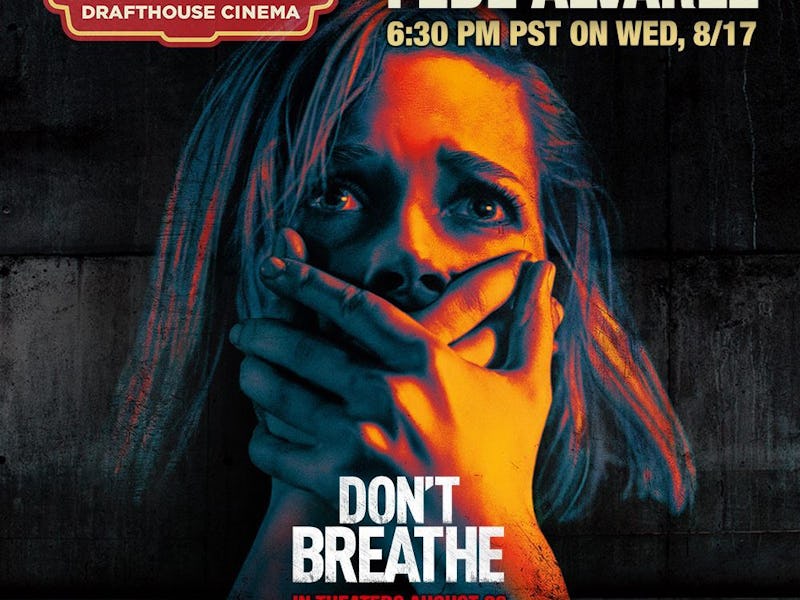

Director Fede Alvarez's latest takes all the horror-thriller ingredients and turns them inside out.

Mainstream horror has gone back to the basics. Films such as It Follows, the Korean-language monster movie The Host, Let the Right One In, and even The Purge are deceptively simple stories that have found great success. The true genius of the meta-craziness of Cabin in the Woods was that it quite possibly ruined everything that came after it. These horror films have been able to turn tropes into a positive, but none have done it as subversively as director Fede Alvarez’s newest film, Don’t Breathe.

The movie is so basic, in fact, that it isn’t much of a horror movie at all — despite being ridiculously horrific. The Detroit-set film is about a small-time crook named Rocky (Jane Levy) who robs from middle class households with the help of her thugged-out boyfriend Money (Daniel Zovatto) and loser pal Alex (Dylan Minnette). She needs just one more mid-level score before she hitches a ride out of town to an easier life in California, and it’s always that last score that goes awry. Her plan: rob a local hermit known as “The Blind Man,” a disabled Army vet who rumored to be sitting on nearly half a million dollars in cash from a legal settlement following his daughter’s tragic death.

The thinking is that the job will be a piece of cake, since the can’t see. Once they finally get there and attempt to break in, the blind hermit (played by the surprisingly buff Stephen Lang) proves he won’t be the easy mark they make him out to be. Soon enough, Rocky and Alex are just trying to navigate the Blind Man’s heavily fortified house to get out alive. It seems a comment made by Money before the break-in to justify what they try to do, that “just because the old man is blind it doesn’t mean he’s a saint,” is much more extreme than they could have possibly imagined.

The simple genius of Alvarez’s movie is that the premise is recognizable enough to equate it with other recent hits of the well-tread home invasion genre, but Don’t Breathe is actually quite the opposite. Instead of the normal spin on the Big Bad Wolf scenario of ruthless killers trying to break into a helpless victim’s seemingly peaceful domicile like Netflix’s recent quasi-gimmicky thriller Hush, You’re Next, The Strangers, or even the climactic house party scene of new classic Scream, the questionable implications of the main characters doing the breaking-in adds the perfect amount of moral cloudiness to the proceedings. Is it the bad guy here being invaded, or what?

'Don't Breathe' director Fede Alvarez.

The audience doesn’t have the safety of rooting for good versus bad like in the plot of more mainstream thrillers like David Finchers Panic Room. And the film doesn’t even busy itself with the nihilistic outlook of terrifyingly manipulative home invasion movies like both versions of Austrian auteur Michael Haneke’s Funny Games either. We initially root for Rocky because her home life is so miserable, and the hope for something better is what compels us to get behind the basic idea of the robbery. She needs this money more than the Blind Man. And yet she’s the one who takes the real initiative in the break-in to rip-off this lonely veteran still in mourning because of his daughter. Don’t Breathe is great because it’s about bad people doing bad things, and who proves to us to be the lesser of two evils.

Eventually, like Rocky and co.’s own false assumption about the Blind Man, things turn out to not be as ambiguous as the audience once thought. Alvarez and co-screenwriter Rodo Sayagues throw in some particularly savage motivations for some of the characters that would even make a Saw movie blush. But it isn’t the blood and guts that matters in the end. That kind of thing Alvarez saved in his previous film when he somehow pulled off the Herculean task of remaking genre godfather Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead and managed to make it good. Raimi, unsurprisingly, served as Executive Producer on both films.

It’s ultimately our expectations and anticipations at stake as Don’t Breathe becomes a sort of feature-length version of the pitch black climax of Silence of the Lambs. Alvarez’s film won’t necessarily reinvent the genre, but it’s part of a new school of films that have taken the basic ingredients and somehow spun them into newly recognizable results. Though the antagonist of the film cant see, Alvarez’s talent is crystal clear.