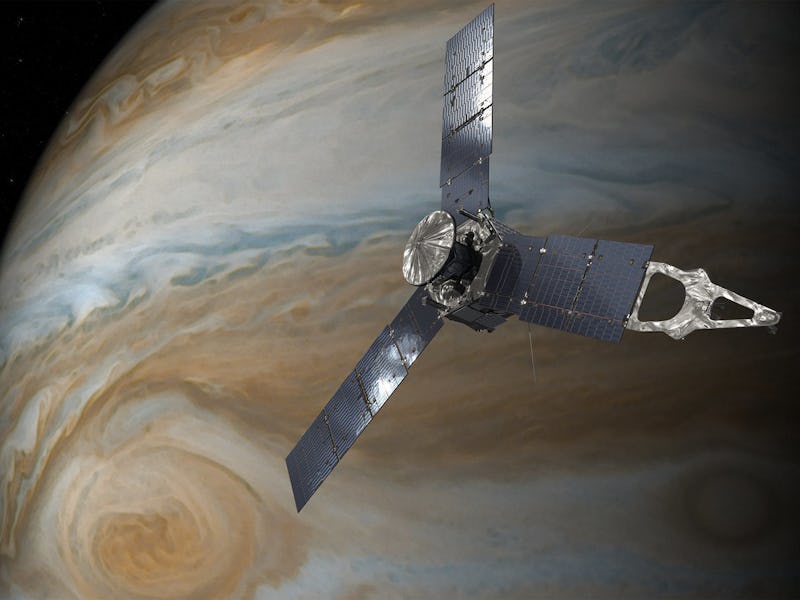

The Juno spacecraft made it to Jupiter in one piece over the July 4 holiday, giving a very nervous NASA a chance to breathe a sigh of relief. Now, it’s going in for a closeup.

Since arriving at Jupiter, Juno has been quietly making its way back around in a 53-day orbit. On Saturday, the spacecraft will once again zoom close by the gas giant and provide us with the some of the best close-up images of Jupiter ever snapped.

At 8:51 a.m. Eastern Time, Juno will make its way toward the top of Jupiter’s clouds and make a closer approach than it has since inserting itself into the planet’s orbit early last month. Juno will be get about 2,500 miles away from the surface of the planet, speeding by at more than 130,000 mph.

This will be just the first of 35 more close flybys for the spacecraft before the end of its primary mission in February 2018.

This dual view of Jupiter was taken on August 23, when NASA's Juno spacecraft was 2.8 million miles (4.4 million kilometers) from the gas giant planet on the inbound leg of its initial 53.5-day capture orbit.

“This is the first time we will be close to Jupiter since we entered orbit on July 4,” said Scott Bolton, principal investigator of Juno from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, in a news release. “Back then we turned all our instruments off to focus on the rocket burn to get Juno into orbit around Jupiter. Since then, we have checked Juno from stem to stern and back again. We still have more testing to do, but we are confident that everything is working great, so for this upcoming flyby Juno’s eyes and ears, our science instruments, will all be open.”

And what might we actually see upon this flyby? With all of Juno’s eight science instruments turned on, including the hotly-promoted visible light imager JunoCam, we’re bound to get some particularly spectacular images. Specifically, NASA scientists will be releasing a ton of high-resolution images of the planet’s atmosphere, including the north and south poles.

It’s going to be an exciting next few weeks, but the real fun starts after October 19, when Juno will undergo another engine burn to bring it to a 14-day orbit about the planet. The images will be much better, and the scientific data the spacecraft will collect (including what’s relevant to water investigations) will be a thousand times more useful.