Stop-Motion Animation Looks Old School, But its Tech Is Incredible

From 3D printing to digital graphics, it's more advanced than you think

A stop-motion animator can spend a week manipulating a small puppet around, frame by frame, for a total of just three seconds of footage. Why would anyone want to do that?

The truth is, fewer and fewer people have the patience for it. But as Laika’s Kubo and the Two Strings recently showed us, the stop-motion animated films can still be incredibly captivating and powerful, even if right now these types of animated adventures are not setting box-office records.

At its core, stop-motion is an old technique, but its practitioners also tend to be technological innovators. Here’s a look at five stop-motion animation advancements that will make you fall in love with the medium all over again.

1. 3D printing

For Kubo and the Two Strings, Laika 3D-printed 23,187 faces of the films title character, Kubo, using rapid prototyping tech and a brand new, color 3D printer. Why? Well, that’s the way the studio carries out its facial animation by using replacement heads for each facial expression.

By first designing all the facial expressions on a CG model and then having them precisely 3D printed, Laika is able to bring more accuracy and emotion to its characters. It’s a technique that was pioneered on Coraline (2009) and has been advanced upon ever since by moving from black-and-white printers to color, and from resin to plastic material (the work was recognized with a Scientific and Technical Achievement Oscar earlier this year, too).

Of course, 3D printing was not really something that many had thought to use for stop-motion animation. “The first time we used [3D printing] for Coraline, it was an untested technology,” Kubo director and Laika CEO Travis Knight told Inverse. “It was meant for producing one-offs in industrial design. It was not meant to be used as a mass-production device. But we saw that it had potential for our medium and that we could use it as tech in service of art.”

For Kubo, the rapid prototyping and 3D printing approach ultimately meant that the main character could have 11,007 unique mouth expressions, 4,429 unique brow expressions, and 48-million facial expressions in total.

2. All things digital

Interestingly, accompanying developments in computer graphics and digital visual effects have also helped both Laika and Aardman’s British Horace and Gromit achieve stunning imagery across films.

Many of the environments and even some of the characters in what might be considered “traditional” stop-motion films are CG. Meanwhile, digital compositing techniques help in placing stop-motion characters shot separately together in frame and filling in green screens and removing puppet supports and wires. VFX is also used in removing the seams that result from Laika’s and other studios’ replacement animation process — the head and mouth pieces are often separate and show a visible joint that is removed in post production.

A stop-motion skeleton puppet for Kubo is captured with a digital SLR camera and stop-motion software against a green screen.

There have been other digital advancements in capture techniques, too, including the use of digital SLR cameras to acquire each frame of animation. Prior to that, film cameras were used and that meant the resulting stop-motion animation could generally not be checked until the film was developed (imagine the hours of work that could have been lost to this process).

Another benefit of using digital SLR cameras has been the ease with which “stereo pairs” of frames can be captured if the film is intended to have a stereo or 3D release. What usually happens is, one frame is shot, the camera is then moved slightly left or right, and another frame taken — all of which can be reviewed immediately and often with the aid of specialized stop-motion software like Dragonframe.

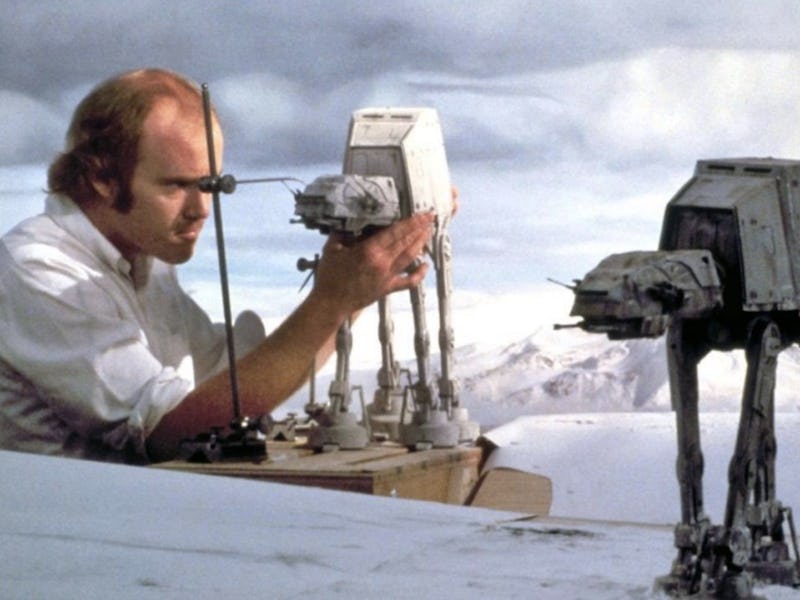

Phil Tippett works on the go-motion animation for Dragonslayer.

3. Go-motion

Stop-motion, of course, far predates any of these advanced digital techniques and technologies. One animator who helped make modern stop-motion popular was Phil Tippett, the animator behind the Star Wars holo-chess sequence, the Hoth ice battle and the rampaging Rancor. He was proud of his work, but also irked by the fact that stop-motion also had a slightly jerky feel, since it did not tend to exhibit realistic motion blur.

With that in mind, Tippett pioneered a technique called go-motion, used extensively on Dragonslayer (1981) for the dragon Vermithrax Pejorative. “Go-motion allowed for very positive registration of the stop-motion puppet, and allowed the puppet to actually move while the shutter of the camera was open, allowing for motion blur,” Tippett said.

Ultimately, the go-motion process, which was essentially a way to capitalize on motion control mechanisms that had already found a place in stop-motion animation and bluescreen visual effects photography, did not catch on. Tippett himself turned to CG animation after being involved in Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park, where his go-motion services were overtaken by new computer graphics techniques.

4. The work of Willis O’Brien and Ray Harryhausen

The work of these two filmmakers, O’Brien and Harryhausen, beginning in the early part of the 20th century does not involve so much a specific stop-motion innovation as it marks a leap in the way the medium could be used for storytelling. Both filmmakers would utilize puppet models fitted with interior metal armatures to tell often fantastical tales that could not be told without the use of stop-motion.

Willis was responsible for such films as The Lost World (1925) and King Kong (1933), while Harryhausen, a disciple of Willis, went on to help produce the animation for Mighty Joe Young (1949), The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) and Jason and the Argonauts (1963).

Harryhausen, in particular, developed methodologies for combining live action with his stop-motion animated scenes, evidenced by the band of sword-wielding skeletons that take on some real human actors in Jason and the Argonauts. This was all achieved with layered optically projected techniques, dubbed “Dynamation.”

5. Claymation

Claymation is a term that many might easily associate with stop-motion animation, especially relating to the films and television shows of Morph and Wallace & Gromit from Aardman, and the work of filmmaker Will Vinton, famous for the California Raisins commercials.

But claymation has really been possible ever since the invention of plasticine around 1897. Being so malleable and having the ability to retain its shape, plasticine enabled stop motion animators to do almost anything with their characters. Once added to an underlying armature, even more performance could be be brought out of a claymation puppet.

Peter Lord, one of the founders of Aardman, leaned heavily on claymation and modeling clay for the animation of his Morph character and on more recent projects. “I feel I invented clay animation the way we were doing it back then,” he said. “Modeling clay lends itself by its very presence in the studio. There’s a certain sort of realism that makes you think about performance.”

Now, of course, what was built with plasticine or modeling clay is being replaced with techniques like 3D printing. Yet stop-motion animation remains a frame-by-frame process, even if many technologies and innovation continue to impact upon the art form.

Aardman co-founder Peter Lord with his plasticine creation, Morph