Real ESP Experiments Inspired 'Stranger Things'

In 1973, parapsychologists got a $52,000 grant from the National Institute of Mental Health. Strangeness occurred.

In the Netflix original series Stranger Things a young girl named Eleven, with a dark past and a deep love for Eggos, is blessed/cursed with the gift of extrasensory perception (ESP).

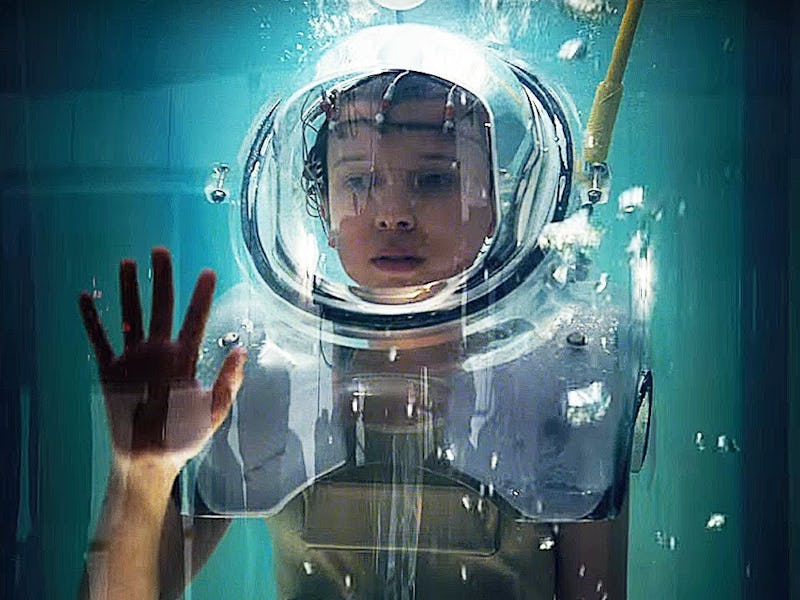

But Eleven is kept captive by her ESP, force-plunged by agents and her controlling father into sensory deprivation tanks — like a secret lab’s upright water tank or in a hacked kiddie pool spread out in a school gymnasium — that allegedly deepen Eleven’s abilities.

That’s not far from the truth.

Eleven in a "Stranger Things" version of a sensory deprivation tank.

In 1973 parapsychology got a vote of confidence from the United States government by proxy of a $52,000 grant from the National Institute of Mental Health — the first grant awarded for parapsychological research that eventually went to the Maimonides Medical Center’s Division of Parapsychology and Psychophysics. Based in Brooklyn, the objective was (as then-senior research associate Charles Honorton told The New York Times at the time) to conduct experiments to prove the existence of ESP.

Honorton and his group had previously focused on “ganzfeld experiments,” a 1930s sensory isolation technique where the “receiver” relaxed in a chair with headphones and halved ping-pong balls over their eyes, a red light shining on them, putting the receiver in a state of mild sensory deprivation. In the 1950s, psychologists began to experiment with the effect of the environment on ESP. The major two methodological variants of “REST” — restricted environmental stimulation — were either a confinement to a room with some sort of stimulation (like a ganzfeld experiment) or reduced stimulation via immersion in a tank of water. This is the sensory deprivation tank — a place of darkness, silence, saturated water, and a ton of Epsom salt.

To understand why parapsychologists — who face their own stigma and are cast aside often as quacks — believe a sensory deprivation experience like one induced in a tank could induce ESP, you first have to have an understanding of how our senses work.

“Sensory deprivation has been used primarily to study plasticity in the brain,” associate professor Ladan Shams of the University of California, Los Angeles tells Inverse. “It has to do with learning — how malleable the brain is.”

When someone is in a sensory deprivation tank, floating in water with a high buoyancy and kept at an outer skin temperature, stimuli like sight are severely reduced. Scientists have learned that when deprivation is very artificial and very transient — you’re not going to spend all day in the tank — then the brain is able to adjust to its new state fairly quickly. However, while the name may be sensory deprivation tank, it doesn’t mean that all of your senses are wiped out when you begin your float.

“If you stimulate one sense, the activation in that sense may cause activation in other senses — so whether you’re in a tank or you’re in a dark room, there’s usually sensations and simulations that still occur,” says Shams. “In a dark room you can still hear, you can still feel, you have access to all these other sensations. In a tank also — even though, it may be dark, you don’t see; you’re floating in the water so there’s less information coming from our vestibular system — you still have sensations from touch, from sound.”

A sensory deprivation chamber.

Honorton’s research team — whose grant only lasted for a year and whose influence has been all but scrubbed now — was confident that sensory deprivation was the key to unlocking ESP abilities at the time, much like the scientists who work with Eleven in Stranger Things. Honorton told the Times:

“The evidence of ESP, not only from our work but from a dozen other experiments, establishes beyond any reasonable scientific doubt that it occurs. It is important that research on ESP now shift from attempts to demonstrate that something unusual is happening — which has been the argument over the last 90 years — to what kind of situations and individuals are necessary for it to be obtained.”

A sensory deprivation tank in Scottsdale, Arizona.

The ability to induce relaxation and a pleasant mood — as well as a desire to experience an altered consciousness — has transitioned sensory deprivation tanks from sixties-era laboratory experiment to a modern-day spa routine. Today, if you’re willing to throw down about $100 for an hour, you can try out a tank in most major cities.

The closest thing our body has to ESP, Shams muses, is when someone experiences phantom limb phenomenon, which occurs when a person has a limb removed; it’s sensory deprivation in the realest sense. The neurons that once were activated by the movement of an arm or leg begin to get recruited by the brain for other things, simultaneously fooling the brain into thinking that the activation of a neuron means that a missing limb is itching.

But ESP remains as fuzzy as ever, with or without sensory deprivation. A 2008 Harvard study argued itself to be the strongest evidence yet against the existence of ESP in an experiment that attempted to see if brains responded differently to ESP and non-ESP stimuli. Still, the authors had to admit that their study couldn’t prove the counterfactual — that ESP wasn’t real either. Which means the example of ESP we see in Stranger Things might not be entirely factual — but it’s not completely impossible either.