Can Old Hackers Learn New Tricks? A Pioneering Con Evolves

Hackers on Planet Earth started in 1994, but the conference is more important now than ever before.

Kyle Drosdick is fixing a Segway in a curtained-off section of the Pennsylvania Hotel’s mezzanine level, surrounded by folding tables and Rubbermaid storage bins that overflow with computer cables like a snake charmer’s suitcase.

“I can’t get this to work. See? Every time I turn it on it just flashes up this weird screen and freezes,” he says. Drosdick has been working on the wobbly Segway for 15 minutes, but he doesn’t look frustrated. Computer hackers love stubborn problems.

Drosdick is the event coordinator at 2600 Magazine, a quarterly publication dedicated to covering the cutting edge of computing and the hacker culture at its fringes. Every few years, 2600 sponsors the Hackers on Planet Earth conference, or HOPE, the longest-running hacker convention in North America, and for the past several iterations, Drosdick has run the show, fiber optic internet networks and faulty Segways in all. The original HOPE was in 1994, making the conference older than some of this year’s attendees.

In mid-July, hackers once converged for the eleventh HOPE con at their traditional meeting place — a hotel across from Manhattan’s Penn Station — and offered their own versions of what the future of hacking, an ever-evolving passion for so many, might look like.

Whenever HOPE happens, it’s a hit, both with the graying veterans of the ‘90s dot com revolution and younger hackers who are pre-dated by dial-up. DEF CON, an annual convention held in Las Vegas, has taken most the spotlight in recent years, projecting a feeling of both efficient organization and menace, as suspected black hat (criminal) hackers rub shoulders with federal agents trying to appear casual. Over the years DEF CON has cultivated a chaotic atmosphere of hacking, spying, and scandal. HOPE, on the other hand, seems almost friendly.

“I put up a honeypot an hour ago to see what people were doing, and nope, nothing!” Jacob, a HOPE volunteer walking by exclaimed. A honeypot, Drosdick explained, is “something that looks tempting to hack,” like an unsecured network or a vulnerable piece of hardware, which counter-hackers sometimes put out as “sort of a diversion to keep you away from the real stuff.” In the time since Jacob had left it there, with several thousand talented programmers wandering around, no one had attempted to hack into his decoy. At DEF CON, this would be a different story.

“That raw hacker spirit.”

“When we started it was a smaller world,” says Emmanuel Goldstein, one of the founders of 2600 and HOPE. “We’ve seen conferences that pretty much just turn into security conferences, and they unintentionally lose that connection to that hacker spirit, that raw hacker spirit.”

The Eleventh Hope, on July 22-24, sold out hacking about 3,000 attendees — space is limited due to the constraints of the venue, the Pennsylvania Hotel — but every talk and panel was livestreamed through HOPE’s website. The panels are varied, and many of the topics don’t relate directly to computer hacking. Instead, HOPE stays relevant by accepting the lighter side of the “hacker” mentality — that at its core, computer hacking is about questioning authority and access to information, but also about applying outside-the-box thinking to complex problems and then just seeing what works.

Attendees chat over various booths in HOPE's main concourse. Black is a popular color.

This philosophy, it turns out, applies to pretty much anything. Panels at HOPE included seminars on car hacking, lock picking, and how to program cybernetic dildos. They also included completely offline subjects like meditation, fitness, and business skills. While a lot of this might seem tangential to the hard-line breaking, cracking, and coding of DEF CON activities, which often feature hacker vs. hacker games of digital “capture the flag” on secured networks, HOPE stays true to the roots of hacker culture by embracing the multifaceted identities of the counterculture from whence it came.

At the third conference, Goldstein invited Jello Biafra — former singer of the Dead Kennedys, Green Party politician, and counterculture activist — to speak, wanting to ramp up the community’s participation in “hacktivism,” and harness the collective force of the hacking community for social and political goals. Biafra was a regular fixture at HOPE for several years, giving keynote speeches and leading panel discussions despite his complete lack of experience behind a keyboard.

“The idealism is here, and I think that’s at the central part of a true hacker conference,” Goldstein says. “It’s not all about security holes and developing some fast bit of technology, it’s about social issues as well. In the beginning, some people were a little bit resistant to [that], because they thought there was no place for politics in the world of hacking. But the fact is that it’s already there. Hacking, politics, it’s always in the same place.”

“Hacker culture” is enjoying something of a moment in popular culture. Digital privacy is a consistent topic in the news after Edward Snowden exposed the government’s system approach to snooping on people online, and high profile hacks have wreaked havoc on politicians and celebrities alike. USA’s hit show Mr. Robot is both a niche favorite with hackers for its lack of “cheesy crap,” and a critical darling.

But it wasn’t always this visible. Sharon, a soft-spoken woman in her 40s who works as a backup and storage systems administrator, says she has been programming since the early ‘80s, a time she describes as “kinda like the wild West.” At the time, basic computing was just starting to catch on, and phone hacking — known as phreaking — was the major tool and toy of people wanting to poke holes in the established order. Sometime in 1983-1984, Sharon says she discovered a bug in the AT&T phone system that let a user call in and access the company’s billing computer. “I told them about it immediately, and they quickly patched that hole, and that paid for my first two years of college,” she says.

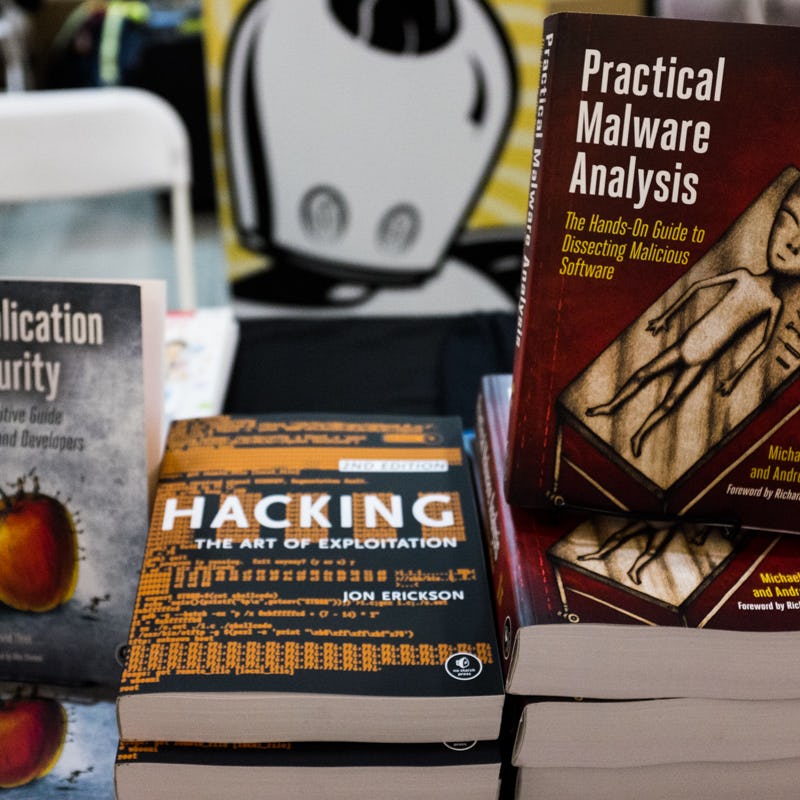

A hacker upgrades the firmware and hardware of his laptop to a non-stock version that provides more security.

As computer technology and its inherent vulnerabilities became more ubiquitous, she says, “over regulation” in the software industry discourages this inquisitive hacker mentality. There was a brief era of rigidity in the corporate software sector during the consumer booms of the 1990s, and hacker culture was first relegated to, and then flourished in the shadows as a turn of the century rebellion against authority. Films like The Matrix, Hackers, and Swordfish all came out, simultaneously misrepresenting, glorifying, and marginalizing the culture. HOPE began right in the middle of all this, in 1994, the first convention serving as a sort of coming out ceremony for the people behind the keyboards. Now, though, the industry is out in the open, but it still struggles with negative connotations.

“Early on, hackers really had to fight for their identity,” Drosdick says. “Now what we’re seeing is this sort of acceptance of hacking; it’s sort of derided, though, in the media, and from an institutional perspective. Governments or large conglomerates have an adversarial view of hackers, even though they themselves would admit that they have entire departments full of them [hackers].”

And as the software and tech industry has developed, some sectors have proved themselves more progressive than others. Kristi Farinelli, a young programmer for IBM who works on its Watson cognitive computer project, says that the over-regulated atmosphere of the ‘80s and ‘90s has been replaced by a free-wheeling “startup culture” where risks are encouraged.

“We have this saying [at IBM] of ‘treasure wild ducks;’ we treasure ideas that are out there, that are off the wall,” Farinelli says. “A lot of times hacking is seeing what works and what doesn’t work, and for our [IBM’s] purposes we can turn it into real world solutions. The hacker mentality is definitely encouraged.”

A network cabinet at HOPE, with appropriate warnings.

As hackers start to find more of a place in mainstream society, HOPE’s organizers see their mission as both evangelists and interpreters for the culture and spirit of hacking. A large part of that is reaching out to the next generation of hackers, like “Ocha” the 13-year-old hacker tapping HTML scripts into his Macbook and learning how to pick locks across the table from Kristi. Ocha said he had been programming for the past two years, and regularly going to 2600 meet-ups.

While Ocha was old enough to navigate the hacker convention himself, Drosdick said in recent years he’s gotten many requests to provide child care at 2066 meet-ups and HOPE events. The rebellious hackers of the ‘90s are now parents, but many of them share 2600’s goals of passing on the spirit of hacking to a new generation.

“The liberation that they had to fight for, to create that identity, is now something that they want to provide for their children,” Drosdick said.

2600 has a good working relationship with Makerfaire, a New York-based tech festival whose audience skews toward young people and educators. Going forward, Drosdick says, “it’s about young people and getting them more involved, and continuing to evangelize about hacking as something that isn’t this scary, demonized thing, that it’s interesting.”

Because technology isn’t going anywhere. As attractive as the concept of becoming a Luddite may seem at times, HOPE’s keynote speaker Cory Doctorow said the advances of modern technology and surveillance are reaching “peak indifference” for the public. “There will be a moment, and I think we’re approaching that moment, where privacy breaches every day destroy the lives of millions of normal Americans,” Doctorow said during his keynote speech.

“I think [the hacker mentality] is more important now that ever, because the world has gotten really kinda messed up,” Goldstein says. “A lot of people are scared of everything these days. What the hackers represent, they represent questioning everything, experimenting, mischief, but being good people… taking care of things, not causing problems or harm.” On Sunday, after three days of constant internet traffic on the 10 gigabyte fiber optic internet connection Drosdick managed to rig up with a collection of salvaged, bought, and donate materials, Goldstein said the conference hadn’t seen any vandalism, digital or physical.