The Bizarre Meteorology of 'Blade Runner'

Why the hell is 2019 Los Angeles rainy all the time? Blame silver iodide.

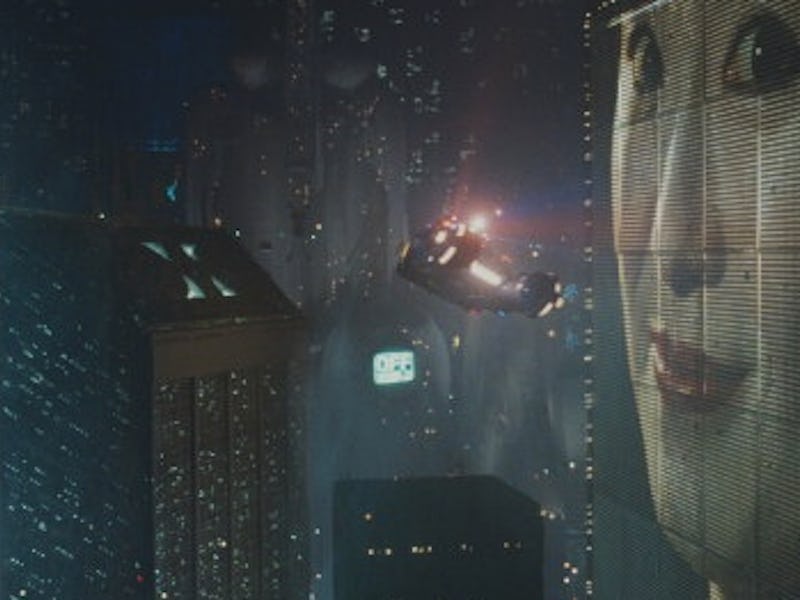

Last week, early concept art from the Blade Runner sequel was released by Entertainment Weekly. Theres not a lot to go on and plot details are still hard to come by, but the concept art makes one thing clear: Just like the original, this Blade Runner film is going to feature an aquifer-worth of rain. Or, as director Denis Villeneuve puts it, “The climate has gone berserk.” But has it gone berserk in a way that makes sense?

The original Blade Runner was a damp affair. Set in perma-soggy 2019 Los Angeles, the film wasn’t intended to be an accurate depiction of near-future L.A. — more of a meditation on humanity. The decision to make 2019 Los Angeles rainy wasn’t borne of scientifically informed hypotheses about the state of weather in the near future. Instead, it was an aesthetic and practical choice. In Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner, director Ridley Scott explains: “It does help lend a realistic quality to the story, yes,” says Ridley. “But really, a lot of the reason we finally settled on all that rain and night shooting was to hide the sets. I was really paranoid that audiences would notice we were shooting on a back lot.”

Given what we know about weather systems and climate, the filmmaking decision was memorably eccentric (if also memorably effective).

Weather Systems

Weather patterns exist because our planet is heated unevenly by the sun. Our atmosphere and oceans distribute and exchange the heat provided by the sun, influencing and shaping weather systems and climates.

Though we understand climates as they relate to particular regions, weather is a complicated and chaotic thing. Variables in weather systems are always in flux, changing the way that weather patterns unfold and give way to precipitation, heatwaves, droughts and cold fronts. There are a lot of determining factors when it comes to climate, but since our question is about whether or not the constantly rainy future LA as seen in Blade Runner is a possibility, let’s move a little bit north to an area that does see a lot of drizzle: the Pacific Northwest.

Now, it’s worth noting that even though Seattle has a reputation for being rainy all the time, the rainfall totals aren’t really that high. In fact, Seattle’s average rainfall is only about 37 inches.

In 2004-2005, LA had 34 inches of rain. Granted, that’s really high for Los Angeles (current numbers are in the single digits), but it’s not as if LA lost its sunny cred. So why the soggy rep for Seattle?

It has a lot to do with the way that it rains. Seattle is quite wet, and that’s thanks to its position between the mountains and the ocean. Moisture is trapped on the coastal side of the mountains, making said coastal area wetter (and thus, the other side of the mountains drier by comparison). Seattle’s rain doesn’t necessarily come in torrential downpours, but the fact that it sits between mountains and the Pacific Ocean means that it’s often quite wet. The same holds true for the entire coastal portion of the Pacific Northwest. Many of the characteristics of the PNW climate are consistent with an oceanic climate, but the fact that there is still a rainy season,” with more rainfall occurring during the fall and winter months, means that it shares some characteristics with the Mediterranean climate seen at lower altitudes.

LA is very much a part of the Mediterranean climate, but the day-to-day of its climate and weather differ greatly from the PNW. It’s further south, it doesn’t have the same topographical features that trap moisture and lead to the soggy conditions we find in the PNW, and, in case you havent heard, it’s in a state that’s experiencing a severe drought. But, striking that last bit from the record, LA has never experienced the kind of profound and prolonged wetness we’ve come to expect from the Pacific Northwest. LA’s known for its sunshine.

Could that change? Barring cloud seeding, it’s hard to imagine LA catching up to Seattle in rainfall consistently. Even with inspired cloud seeding efforts, the practice isn’t a magic silver iodide bullet.

Cloud Seeding

A decades-old method for weather modification, cloud seeding uses a chemical like silver iodide to increase rainfall from clouds that are already going to produce rain. It’s not a method for creating rain, it isn’t a way to control the weather, and it’s far from what you might call Storms On Demand.

Its more like a boost — think of it as espresso for clouds. If all goes well, seeded clouds might produce 10-15% more rainfall than they would’ve if they hadn’t been seeded, and while thats a significant enough return to have California putting some cash juicing up clouds, it’s a long way from taking LA from the dry and sunny City of Angels we know to the drizzly city we see in Blade Runner.

So is the rainy 2019 Los Angeles of Blade Runner unrealistic? Yeah, probably. But as Scott said, the choice to make Los Angeles rainy in the film was largely aesthetic and came from a need to make a small studio back lot work without giving away that it was small and a back lot.

That’s very much in the spirit of Blade Runner, and it sounds like that spirit’s going to be carried into the sequel as well. Villeneuve told EW that he had coffee with Hampton Fancher, who adapted the original film’s screenplay from Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, and Fancher gave him some insight regarding the film’s logic.

“He told me that Blade Runner was a dream,” said Villeneuve. “We just have to dream again and not worry too much about logic. That removed so much pressure and gave me the key to move forward.”

If the concept art is anything to go by, it looks like rain’s going to be a part of the dream again in the Blade Runner sequel, though it’s hard to believe that this time it’ll be out of necessity. A fundamental piece of the traditional noir aesthetic and now an inextricable part the Blade Runner world, the rain isnt realistic, but it is impactful.