The Reason Why Mars Is So Freaking Cold Is Dust

The new data might help NASA decide where to one day place human colonies.

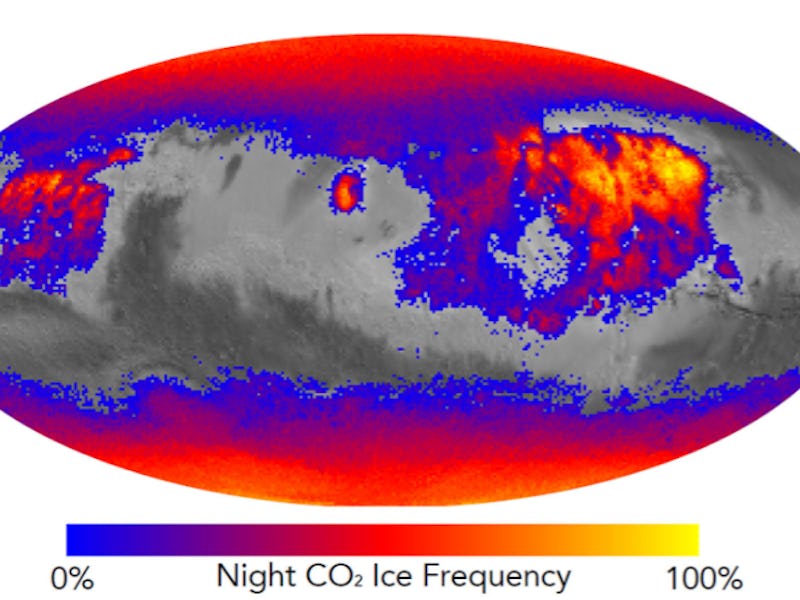

NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter has sent back data allowing engineers to piece together a map of just what regions on the Red Planet get really, really cold — even near the equator, and even in summer.

The extremely low temperatures are enough to cause a strange and alien (well, at least to us) phenomenon — carbon dioxide frosts. Certain regions of Mars are so dusty that it interferes with the atmosphere’s ability to retain heat, leading to huge temperature swings — big enough, in some cases, to allow the carbon dioxide frost to form overnight.

Specifically, there are three regions on the planet’s surface where nighttime temps drop low enough for carbon frosts all or most of the year. In the mid- or low-latitudes, they’re disproportionately dusty and thus prone to massive and sudden temperature swings. The swirling dust forms a kind of fine, blanketing layer over the rocky environment. These regions get even colder than the planet’s poles.

“These same regions that are coldest at night are the warmest during the day,” Sylvain Piqueux, lead author of a Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets report on the findings, said in a release. “It has to do with the nature of the material — it’s so fluffy. Think of when you’re at the beach on a summer afternoon, where you step on the fine grain sand. You almost burn your foot, it’s so hot at the surface, but just below the surface it’s not as hot, and if you touch a boulder, it doesn’t feel as hot. Then it’s the opposite at night: The surface of the sand cools off quickly, while the boulder stays warm.”

It’s still a little premature to guess at all the implications of the new data, but this has the potential to inform where scientists focus on landing future Mars rovers - and, eventually, where to build human colonies. These dusty, carbon-frosted, ultra-cold regions would seem an unnecessary strain on resources, not to mention the possibility of degrading the technology at a faster rate than would other regions of the planet.

NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter began its mission in 2005, and has been transmitting findings since 2006, searching for signs of historical water on the planet’s surface. The data it’s sent back over the last decade has been so valuable that the mission’s been granted multiple extensions.