Meet This Tiny Robot Stingray Powered by Rat Heart Cells

The innovation in tissue engineering is already being used to fight pediatric disease.

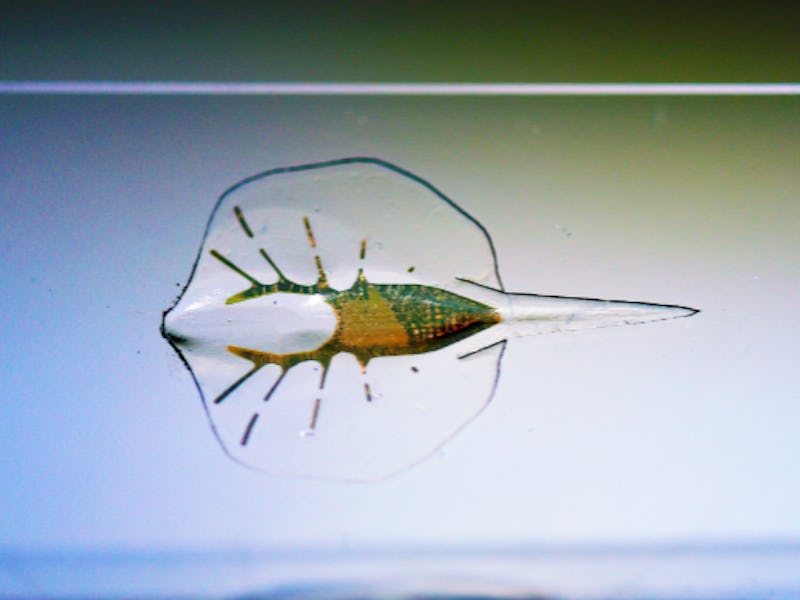

Researchers have created a bio-inspired robot that actually incorporates organic elements: It’s a mechanical stingray powered by the light-sensitive heart cells of rats.

In a study published Friday in Science, the authors explain an awesome breakthrough in tissue engineering: When the rat cells are stimulated, they contract the robot’s fins downward; the design allows some of that energy to be stored, redirected, and used to make the fins rise again.

The muscle cells were genetically engineered to respond to pulses of light, which is how the researchers control their movements. The asymmetry of the pulses they send determines whether it turns left or right, while varying the frequency of the pulses controls the robot’s speed. The effect is so precise that the stingray can be successfully steered through an obstacle course.

The optogenetic technology is already being used to treat ventricular arrhythmias in children, said Kevin Kit Parker of Harvard’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering. Parker, the senior investigator on the project, first had the idea four years ago during a visit to the aquarium with his daughter. But due to the project’s complexity, it took a year to persuade lead author Sung-Jin Park to get on board and to get all the funding in place.

“Yesterday was a very emotional day at the laboratory,” Parker said. “We’ve been cranking on this thing for years, it cost an ungodly amount of money … all the lessons we’ve learned from this exercise are already being used in the fight against disease.”

The stingray was essentially a training exercise for the researchers. Parker and his colleagues began studying marine organisms, working under the assumption that they could use cardiac muscle cells to replicate their musculature and their hydrodynamics, or their swimming performance. They’d built a jellyfish in 2010, their first attempt at working with the muscular architecture in this fashion. The serpentine pattern of the robotic stingray approximates the skeleton of an organic one.

The stingray measures just 16 millimeters long and weighs 10 grams - yet contains about 200,000 cardiac cells.

Parker says he’s primarily interested in the heart; he wants to build one. But in order to get to that point, he and whomever he works with in the future need to train themselves with control experiments like this one. After this month, he says, they’re never touching the stingray again — they’ve done what they came to do.

The tiny stingray lies at rest on a titanium mold.

“Oh, we have a plan,” said Parker. “But I’m not gonna share it. We do not know how we’re gonna pay for it. And it might not work — I might not find another Sung-Jin. He is a beast, he is an animal, I’ve never seen a scientist like him before. I’ve dubbed this the synthetic beast, it’s an ode to him.”