What Is 'Lone Wolf and Cub' and How Can it Work in Hollywood? | Looking East

With a Hollywood version on the way, can a Japanese classic manga stay relevant in 21st century America?

The Tokugawa shogunate, Japan’s final military government, ruled the island nation from 1603 to 1867. Referred to as the Edo period, these 264 years in history have been a boundless source for medieval-centric mythology and Japanese pop culture, ranging from Akira Kurosawa movies to Samurai Champloo.

Lone Wolf and Cub, a manga written by Kazuo Koike and drawn by Goseki Kojima, has been one of the longest-lasting and most important of these period interpretations. The book, a mega influential manga about a disgraced executioner on a blood-soaked road to revenge with his infant son in tow, ran from 1970 to 1976. Later, the comic was adapted into a handful of movies and TV shows, including 1980’s Shogun Assassin (a personal favorite of Quentin Tarantino) and 1992’s Lone Wolf and Cub: Final Conflict, directed by Akira Inoue. Now, America is getting in on the action.

Earlier this week, it was announced that Hollywood producer Steven Paul will be leading a remake of Inoue’s Lone Wolf and Cub: Final Conflict. Paul, while also producing the Scarlett Johansson vehicle Ghost in the Shell. Lest you think this Lone Wolf and Cub will star Russell Crowe carrying a katana, Stevens told Variety his movie will feature an “essentially” Japanese cast.

But what is it about Lone Wolf and Cub that’s so attractive? Why does an award-winning director like Darren Aronofsky dream of adapting it? Why did Max Allan Collins, as he confessed, unabashedly remake it in his Road to Perdition? Why has Frank Miller, the game-changing writer of comics in the late ‘80s, cite it as one of his biggest inspirations? Easy: Aside from being dope, Lone Wolf and Cub exudes a masculine energy with classic (and for others, exotic) bushido values in a grounded and violent realistic setting. It’s these elements that an American-made Lone Wolf and Cub should lean in to if it hopes to be worth anyone’s time.

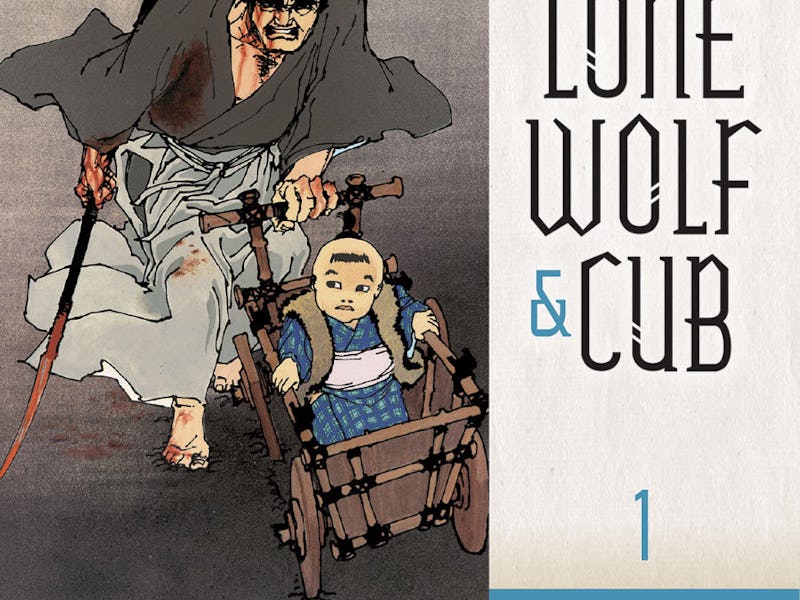

'Lone Wolf and Cub' Omnibus Vol. 1, cover by Frank Miller

So wait, why’s a samurai walking with his kid?

Buckle up, because you’re about to get a crash course in the complicated Shogunate structure.

Ogami Ittō is our hero (or rather, “hero”), a master samurai warrior serving as the Kogi Kaishakunin (Shgun exeuction). It’s a high-ranking position in the Tokugawa military government, and it’s a nasty one: Ogami’s job is to decapitate the samurai and lords ordered to commit seppuku — ritual suicide to maintain one’s honor — to spare them the agony. He’s entitled to wear a valued crest of the Shogunate, and allowed to act in the Shogun’s place.

Things are going well, especially when Ogami’s wife Azumi gives birth to Daigorō, their baby boy. But that doesn’t laugh; soon Azumi and the rest of his whole household, save for little Daigorō, are slaughtered. Ogami gets bloodthirsty and thinks he nails the culprits until he discovers it was Yagyū Retsudō, leader of the rival Yagyū clan. The group is hoping to seize Ogami’s position as part of a plan to control key positions of government, including executioner. Ogami is framed when a funeral tablet with the Shogun’s crest is placed in the Ogami shrine, signifying a wish for the Shogun’s death. For this, Ogami is banished.

Daigorō joins his father on his road to isolation. Now, with his son in a wooden carriage, Ogami swears revenge against the Yagyū clan and dedicates himself to reclaiming his honor. Their journey takes them everywhere, from tracking down Yagyū family members one by one to fighting off whole ninja clans.

Why is this badass?

On the surface (and without all the bloodshed), Lone Wolf and Cub could look like a silly comedy series: A samurai with a baby? How wacky! Instead, Lone Wolf and Cub is a blood-soaked meditation on a Japanese understanding of honor and masculinity.

The immediate draw (no pun intended) to a visual medium like comics is the art, and Goseki Kojima’s illustrations are populated with busy, frenetic energy. Every frame looks like it’s in motion, and Kojima’s depictions of samurai and ninjas at war is hyper-violent and quite gruesome.

A page from 'Lone Wolf and Cub' Vol. 1

Now contrast all of this death and violence with having to care for a child. A tiny child. Not only is it hard to go nuts as a killer when you’ve got a baby to care for, but you also have to wonder what kind of influence you leave behind. It’s not just about perverting innocence — Ogami keeps weapons and booby traps in Daigorō’s wood cart, a signature of the series — but normalizing murder.

This isn’t a major part of Lone Wolf and Cub, but it’s within the subtext in quite a lot of panels. We may think older medieval eras were primitive and savage, but people centuries ago were anxious about this stuff too.

You can see Ogami’s rage contained in so many of Kojima’s illustrations, so it was key when making the movies that the actor nail the part. Tomisaburo Wakayama played Ogami in all the Lone Wolf and Cub movies that were not only popular in Japan but in the U.S. as part of the budding grindhouse/cinema nerd circles of the ‘70s and ‘80s. Wakayama oozes pent-up rage in every frame, and helped propel the movies beyond mere “comic book movies.”

But it’s the presence of Daigorō that really emphasizes Ogami’s anger. In almost all illustrations, whether in Frank Miller’s official panels or the stuff from fans on deviantART, Ogami is frequently drawn like a sourpuss, and pairing that with Daigorō’s cuteness can be result in a fascinating zen-like balance between power and innocence.

Can a Hollywood ‘Lone Wolf and Cub’ work?

There’s a lot working against an American Lone Wolf and Cub. The most glaring is that producer Paul Stevens secured the rights to 1992’s Lone Wolf and Cub: Final Conflict, which deivated from the established hallmarks without much reason (notably ditching the wooden cart that’s so ingrained in the story’s iconography).

A fan illustration of 'Lone Wolf and Cub' from "kungfumonkey" on deviantART.

But more important than getting the comic right, in the hands of a bad filmmaker the story of a trained killer caring for his son on a lonely journey plagued of violence can lose its thematic poetry; a director who favors spectacle would not be the right choice. Stevens’s previous produced works — Marvel’s Ghost Rider, adaptations of the Tekken games — don’t inspire confidence.

There’s also a concern that Hollywood just doesn’t get the nuances of medieval Japan. Hollywood doesn’t portray ancient Japan (or ancient any other countries, really) in accurate or flattering lights. The miniseries Shogun, based on the classic novel, was less about the complex society of that time, but instead about white people exploring an exotic locale. The Last Samurai, starring Tom Cruise, was also about a white guy — an American white guy — and was set in the Meiji Restoration, the period that followed Edo. So a Hollywood movie faithfully setting a Japanese story in its proper time and place seems too good to be true.

But there are some damn good examples to follow, and oddly enough, one is Road to Perdition, the film that turned Lone Wolf and Cub into an American story; Sam Mendes faithfully adapted the heart of the story, even if it was set in Prohibition America. The film even has a killer with a skin affliction, a slight left turn from the tattooed assassin that pursues Ogami and Daigorō.

But more important is the gravity of the situation Tom Hanks’s Michael Sullivan finds himself in and the perilous road (literally and metaphorically) along which he drags his son. It’s actually a universal one: We’re all protective creatures, and it’s instinctual to protect our kin. If Lone Wolf and Cub can nail that, there’s nothing to fear as a Hollywood adaptation of this medieval noir slowly becomes reality.