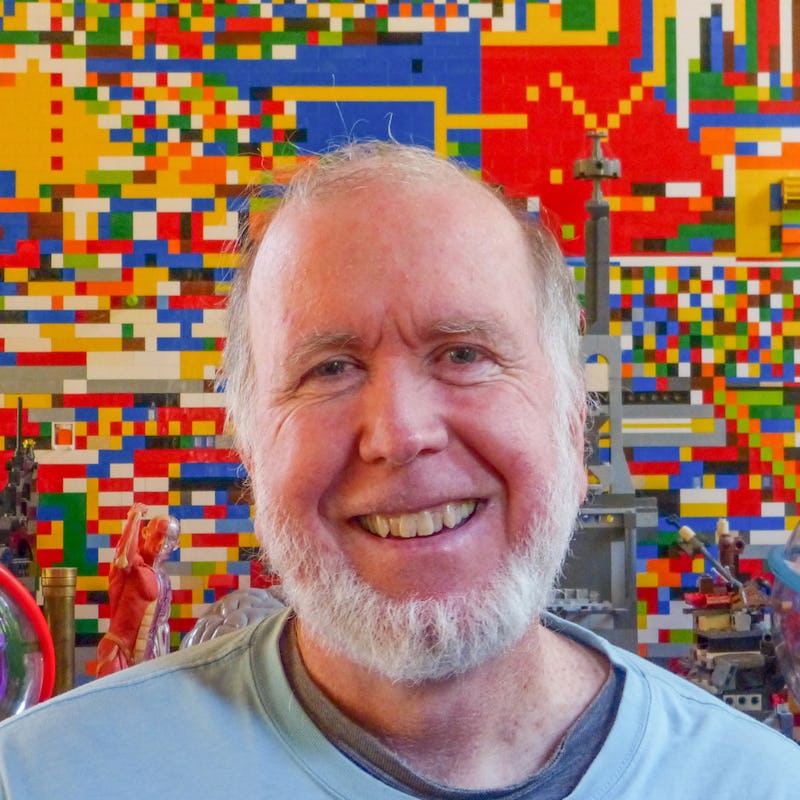

Kevin Kelly Says Pessimists Ignore Evidence and Progress is 'The Inevitable'

Kevin Kelly argues that technology is reshaping our culture for the better.

In the next 30 years, the world will undergo an astounding technological revolution. A.I. and VR will become inextricable from our lives. Everything will become “cognified,” even household chores. In his new book The Inevitable, author and Wired magazine founder Kevin Kelly describes the forces that will shape our world into one where the internet is indistinguishable from the physical world.

The Inevitable is the rare book that can get away with long passages of jargony brand-speak generally best left at Silicon Valley corporate yoga retreats, because it alternates them with passages of arresting clarity. It’s also a fascinating resource for anyone too young or simply disinterested to have witnessed the birth of the modern internet — Kelly writes from the front lines. The Inevitable covers not just the future, but the history of music, movies, and the written word (everything will soon become one big linked, interconnected universal library, if you were wondering). In the future, everything will look kind of like Tony Stark’s 3D tactile computer system (more sophisticated, Kelly clarifies). Goods will be replaced with services, ownership with subscriptions. A.I. will replace routine doctor’s appointments. You will be able to get a “full cardio workout while chasing dragons.” The future will be flawless and shiny and awesome.

How long did you spend writing this? Did it feel like there was a particular rush to get it out while it’s still current-sounding?

Interesting backstory on that. The book was finished a year ago — completely done. It was supposed to be out in fall of 2016 and I was like, ‘no…’ The Chinese actually translated and published it last October. That was about the speed I would have liked. But it was written over a span of at least 10 years. Not full time, but I’ve been talking about and writing about this stuff for 10 years now.

The biggest question the book raised for me was regarding how you see different areas of the world lagging behind or catching up — you describe this juggernaut of technological progress in the next 30 years as a worldwide phenomenon, as if every place had the technological and economic privilege of Silicon Valley — how do you account for that?

There is maybe a focus on America, yes. But developing countries have a two-tier system, where within the capital cities they’re not very far behind and there’s this large middle class, but then, yeah, there’s this other half of the world at least who is not there and they’re without all this. About that Id say, they are moving as fast as they possibly can, just at different rates. China’s moving much faster than parts of Africa. But they’re generally following the same developmental sequence of things. I haven’t really seen a lot of regional differences — there are lots of regional innovations, like in Kenya with electronic payments (most of the rest of the world outside America doesnt have paper checks, they’re terrible). But the kinds of things I’m talking about I think apply equally to the developing world, it’s the same as here.

Your book points out how no one who studied human nature would ever have believed even a few years ago that people would spend so much of their time generating so much content for free, yet here we are.

Everything I’ve seen suggests to me that there will be more content. Tools for making things get easier to use and so amateurs can make increasingly complicated things; that can be satisfying. With the assistance of A.I. we can create more and more and more self-generated content. But I also want to be clear that most of the things in our lives we’re not going to make ourselves; someone else will. The question will be, with new technology, can amateurs make things as good as the professionals? Sometimes.

Im not forecasting a world where everything is crowdsourced to amateurs; we still increasingly want the best. But the tools for amateurs are getting better, faster. There will still be professional photographers 100 years from now. There won’t be very many, but there will be some.

Are there any obstacles to this bright techy future?

One thing that concerns me is whether we’ll treat our robot servants like slaves, because that position can be corrosive to us, but again, that’s not denying the general trend.

My optimism is rooted in two sources; one is history. I’m a radical optimist because I read a lot of history these days. And also because in the ’70s when I was young, I had the fortune to get in a time machine and go back two centuries — in Nepal and Afghanistan and Myanmar. I was living in the 1500s there, nothing had changed and I got to feel and experience what life was like without this technology, and see 200 years of development happening in 20 years. So I have a really deep-felt appreciation of the trajectory that I see us on. There’s a current pessimism in America about the future that does not at all jibe with the actual facts. By every metric we care about, the world really is getting better. Education, rights, it’s all getting better, and yet there’s the sense that things are getting worse, which is just not true. Maybe the progress is slow, we’re creeping to betterment, maybe one percent a year. I’m protopian, not utopian. One percent might not be visible, but really it’s huge. That’s what makes a civilization.

What if Moore’s Law stopped? If we came to a complete brick wall there, if 10 years from now things stopped getting better, faster, cheaper every year? Would that change the trends? I haven’t worked through that, but I suspect now. It might slow them down, but I don’t suspect these trends would stop. As far as anything preventing or derailing this, if there are obstacles I don’t see them. And the reason is that the origins of these trends are not in society. The origins are baked deeply into the very physics of the technology itself.

I think technological systems have biases rooted in the very nature of these physical things. Even software is ultimately physical. The biases in the technology are things that recur independently. The internet would appear on any planet in any civilization in the galaxy. Once you have phones and wires, you’re going to have the internet. The internet is therefore inevitable. But Twitter was not inevitable, the specific character of the internet is not inevitable. Those are the things we have a choice about, and that choice makes a big difference to us. And we should embrace these technologies. One, because we don’t have a choice. And two, because we do have a choice about their character, and the only way we can steer that character is by engaging with them. We can steer the choices that we do have.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.